BEIJING — The Bureau of Labor Statistics, one of the U.S. government’s marvelous data gathering groups, has spents months making public facts about job and business growth that tell an unexpected story about the American economy. Two of the biggest generators of new jobs and rising incomes in the United States — the Great Plains and the Ohio River Valley — were regions all but given up for dead a generation ago.

The northern Great Plains in the 1980s became the focus of a proposal to transform millions of acres into a treeless wilderness “buffalo commons.” The Ohio River Valley was the site of epic dismantling of the country’s industrial manufacturing rust belt infrastructure.

In the last two years I’ve traveled and reported extensively from China, the Great Plains, and the Ohio River Valley. The three regions are tied to each other in ways apparent and distinctly possible only in the 21st century. And two of the regions — the Great Plains and the Ohio River Valley — would be grievously injured if the United States actually makes good on the rising chorus of threats, particularly from the Republican nominee, to pursue sanctions against China for alleged currency and trade infractions.

I write from China, at the start of my sixth trip here in 23 months. A little more than a week ago I was in Indiana and Kentucky. Late last year I was in North Dakota and Montana. In every one of these places there is new prosperity, new jobs, and new connections that are linked to China’s expanding economy, and especially to this nation’s rising demand for oil and for grain.

That demand has helped to keep energy and grain prices high, enabling gas and oil developers to do such things as turn North Dakota into the country’s second largest oil producer, and pour billions in new energy-related investments into Ohio, the fourth largest job generator in the U.S. over the last year.

Similarly, American farmers are doing very well, despite the 2012 U.S. drought. China is a big player in global corn and soybean markets, and prices for both are at or near historical highs. John Deere and Caterpillar, makers of farm and construction equipment in Midwest factories, are doing very well.

A significant downturn in China’s economy — which some analysts say has already begun, but which is also not at all visible in this city’s jammed streets, restaurants, subways and train stations —

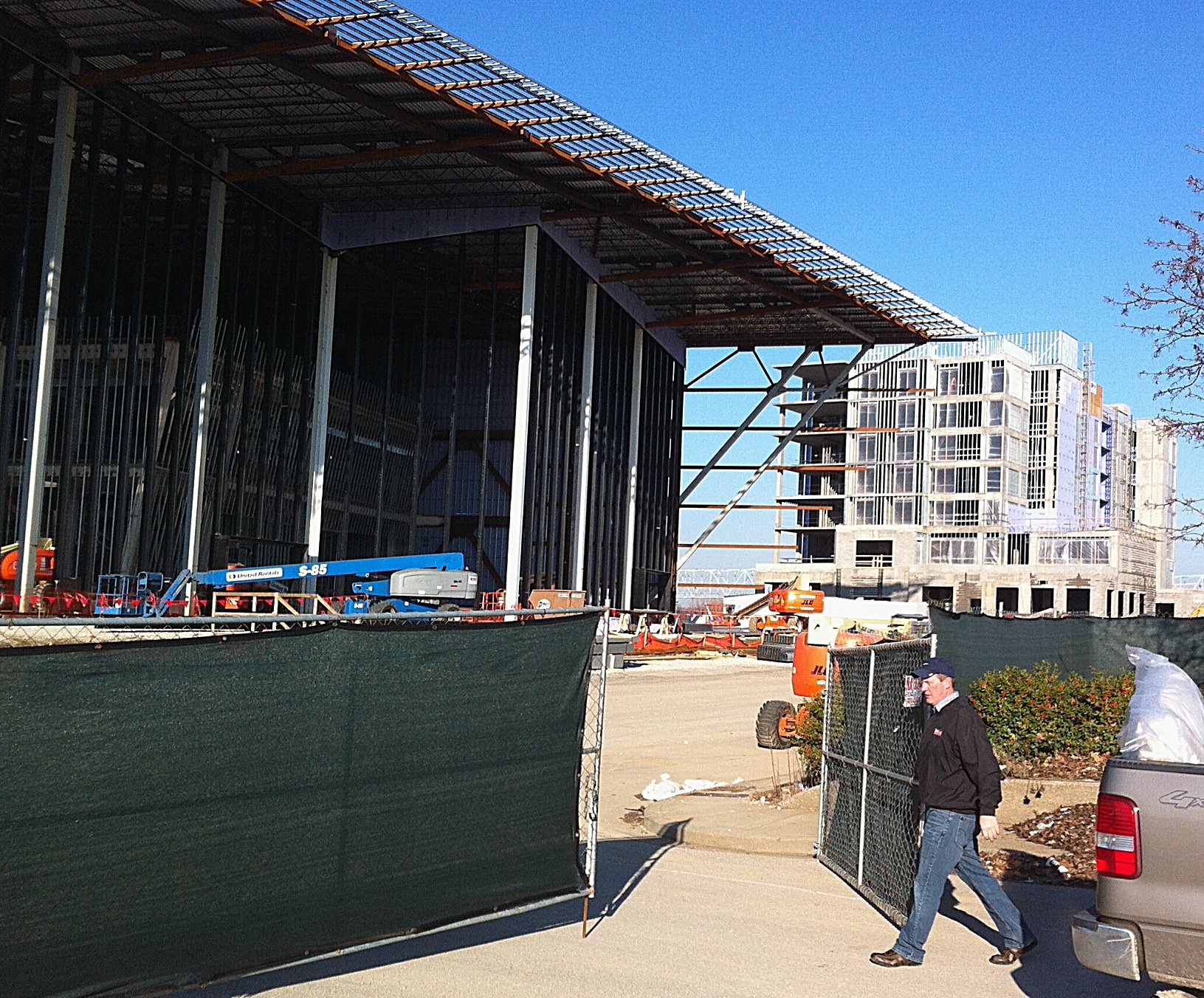

would have the effect of pushing prices down in the U.S. Just as they are essential foundations of the economy here, so too are energy and agriculture significant to the new strength of the economies of the Great Plains and the Ohio River Valley. A negative turn in prices would be felt by energy producers, farmers, and all the ancillary industries and sectors that supply both including the Midwest’s steel industry, which is actually expanding in Ohio after decades of decline.

So when President Obama imposes a 35 percent tariff on Chinese-made tires, as he did at the start of his presidency at the behest of union supporters, and Mitt Romney accuses China of “cheating” and manipulating the value of its currency, no voter in the Great Plains or Ohio River Valley should cheer.

China reacted to the Romney statements last week by warning of a trade war. We’ve heard such threats before from Beijing. Frankly, though, if such a war occurs China appears in far better shape to win it than we do.

— Keith Schneider