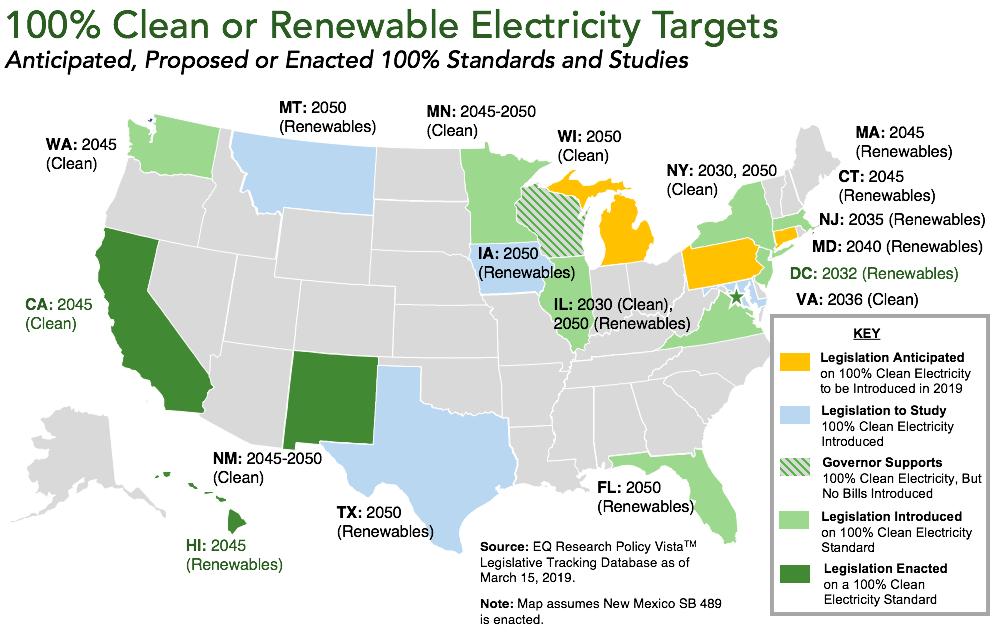

MORGANTOWN, W. Va. — Last September California affirmed its commitment to supply all of the state’s annual demand for electricity with renewable sources of energy by 2045. New Mexico enacted similar 100 percent renewable legislation. This month Minnesota pledged to be the third U.S. state to achieve 100 percent renewable electrical generation, committing to do so by 2050.

The three states are joined by nine other states considering the 100 percent commitment, and 100 American cities that made the 100 percent renewable pledge.

Bravo! In the global contest to slow the advance of warming and dangerous meteorology Americans are investing in industrial evolution and human safety. The idea that clean energy is a path to planetary sanity is alive with elected leaders in American cities, and select counties and states. The advance of the rational energy brigade was felt only three years ago in the White House and Congress, too. But maybe that changes in 2020.

But even as technology, competitive prices, and consumer demand opens electricity markets to clean energy — at a rate considerably faster than most energy analysts anticipated — one fierce headwind is pushing hard to stall the advance. Behind that headwind is a storm of natural gas.

Since 2010, when I first reported on the unconventional energy boom sweeping across the United States and Canada, the dimensions of the development of new sources of oil and natural gas have only grown larger. Last year developers produced 29 trillion cubic feet of gas or 79 billion cubic feet per day. This year, according to the Energy Information Administration, wells in the United States are projected to produce 101 billion cubic feet per day.

So much fuel is being unlocked by fracking practices from gas-saturated shales across the country that the EIA says there is enough to supply national demand for heat and electricity and chemicals for a century. If that’s true, natural gas today is in the same position as coal and oil were in the early decades of the 20th century — as the fuel of the century.

And that conclusion spells potential trouble for the environment because it leads to a surplus of end products the planet does not need — more climate changing emissions and more plastic.

It was only 15 years ago that hydraulic fracturing began to crack deep shales, and natural gas was promoted as a “bridge fuel” to the next era of energy production. That seemed logical. The cost and ecological consequences of coal were rising to unattractive levels. Power plants here and all over the world began to shut down. Coal production reached its peak mid-decade and began to dive. Carbon emissions in the United States also fell.

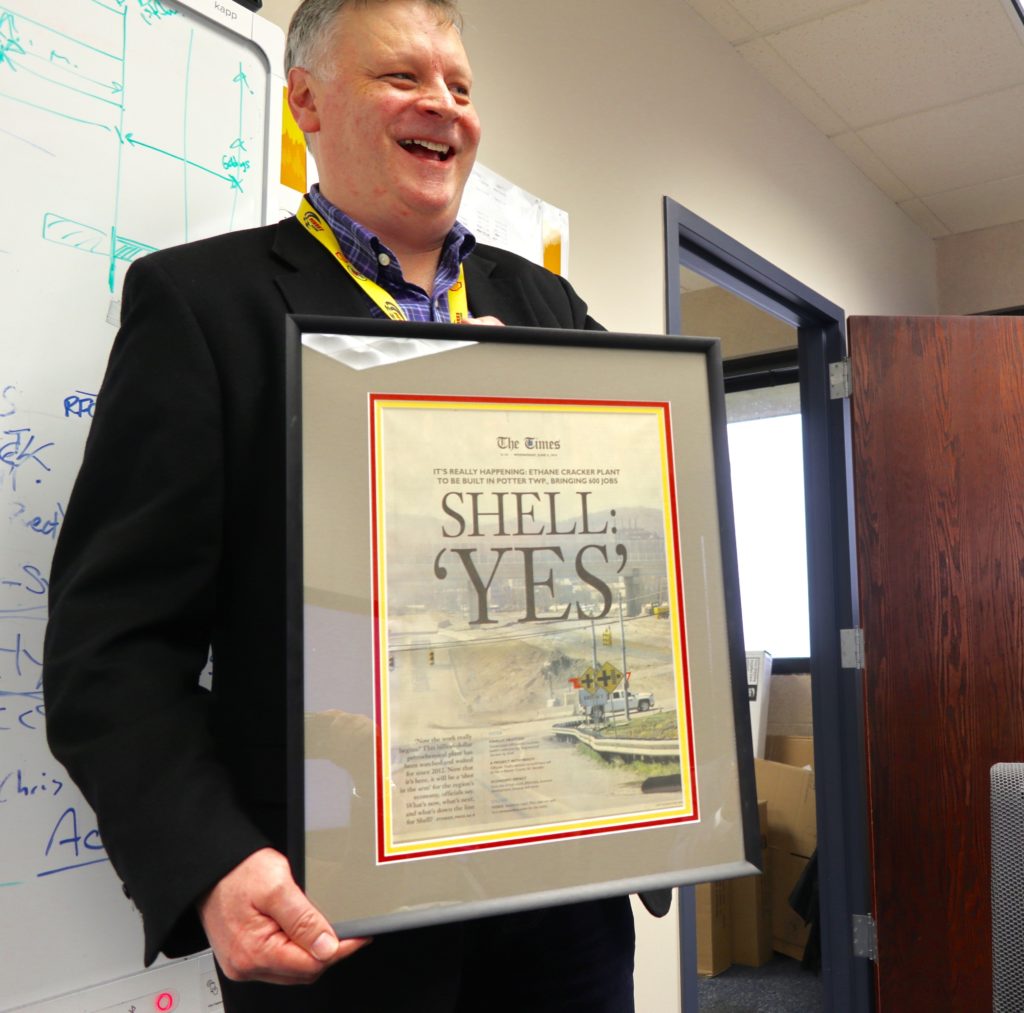

Now new gas-fired electrical stations are opening across America. And in the Northeast the ethane, propane, and pentane from the so-called “wet” shale formations of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia are yielding a new chemical corridor along the upper Ohio River valley. Ethane is the basic feedstock of polyethylene, the raw material for plastics production. Royal Dutch Shell is building a $10 billion polyethylene plant downriver from Pittsburgh in southwest Pennsylvania. A Thai/South Korea consortium is considering a similar-size polyethylene plant along the Ohio River in Shadyside, Ohio.

A pragmatic view of the upper Ohio industrial investment in gas production is that a region that has experienced two generations of economic ruin was due for a resurgence. Good jobs with family-supporting wages are coming on stream. The new plants are cleaner than the polluting metals and steel mills they replace.

But there is a cost to the environment, public health, and the public treasury, too. Methane emissions are more damaging than carbon dioxide, and speed up climate change. The volatile organic compounds released to the air and water are a hazard. The influence of gas-fired electrical generation impedes the spread of renewable technology.

Lastly, the states and the federal government are making big investments in gas in the Northeast. Pennsylvania approved a $1.65 billion, 20-year tax relief measure to encourage Shell to settle in Monaca. Ohio is weighing its own billion-dollar tax subsidy for the Thai/Korea plant. And the Trump administration is considering a $1.9 billion federal loan guarantee to build a big gas liquids storage reservoir in West Virginia.

One conclusion that seems easy to reach in considering all of this: If states and the federal government are prepared to spend $5 billion or so in energy ad fuels development, a better investment is solar and wind and biofuels, which yield more jobs, and much greater levels of ecological and human health safety.

— Keith Schneider