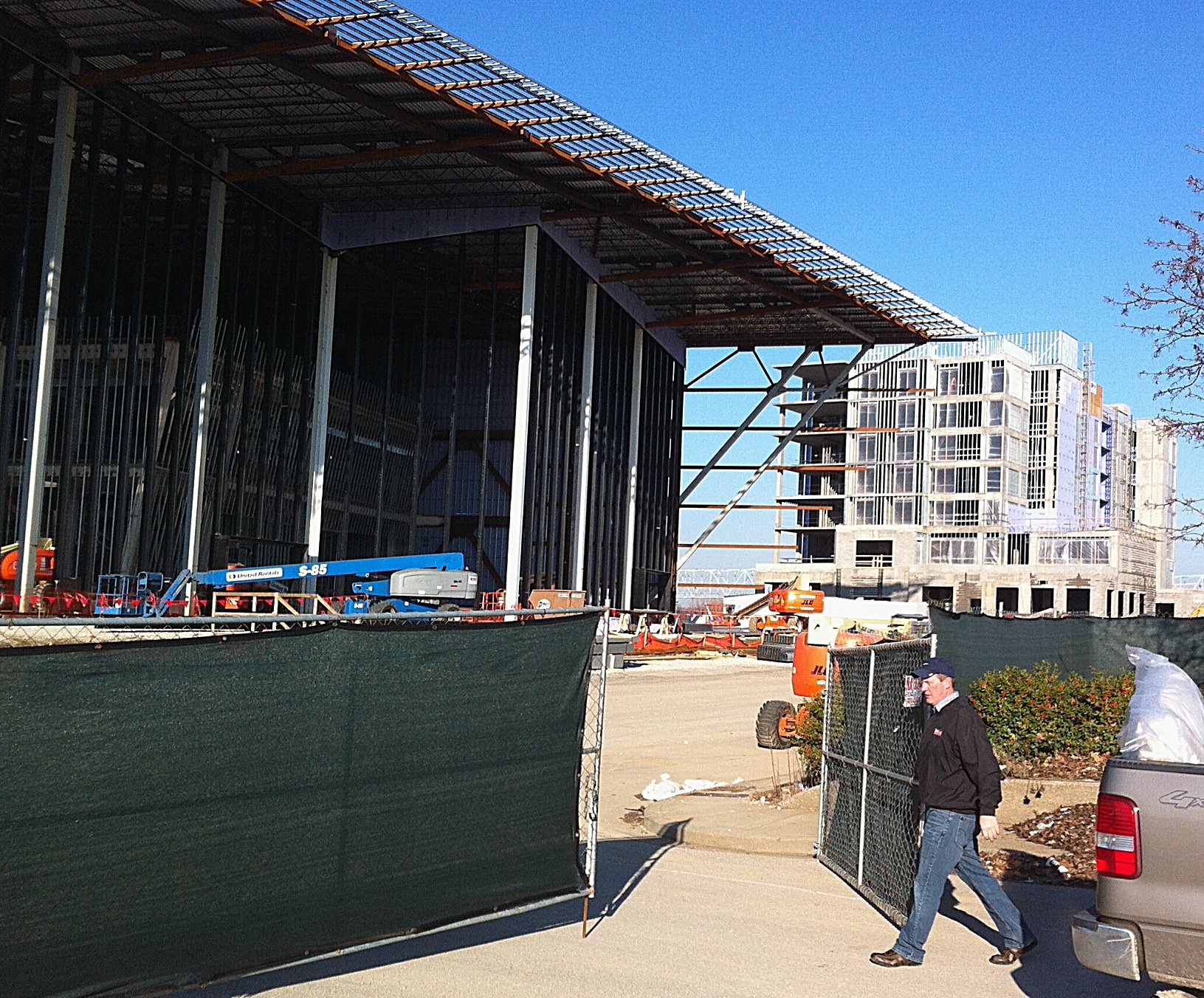

Next week I return to the Ohio River Valley for The New York Times to 1) report on how oil and gas mineral leasing is making thousands of Ohio River Valley working families wealthy, and 2) how new urban development strategies, including a streetcar line and a $1 billion mixed-use riverfront project, are writing a 21st century narrative for Cincinnati’s economy and quality of life.

Later this summer, I’ll report on similar trends emerging in Louisville.

These article ideas and others I reported in recent months tell a vitally important story about the people and places that are inventing the rapidly evolving and much healthier new economy of the Ohio River Valley. Last year, during a five-month What’s Done, What’s Next: A Civic Pact project in Owensboro, Kentucky, I was afforded a rare opportunity to understand how a mid-size Ohio River city decided to take a number of exceptional steps to prepare itself for the new market opportunities of the 21st century.

As I noted several times in the project’s public meetings, Owensboro’s development strategy is nationally significant, a point stressed in a Times article on November 15, 2011.

Perhaps the most important dimension of Owensboro’s chosen path is its ability to embrace development as a shared responsibility. That single value, understanding that collaboration is essential to achievement, is a departure from how states and the national government are contending with the rapid change that is engulfing the country.

What’s Done, What’s Next: A Civic Pact also allowed me to spend time in Louisville and Evansville, and to tour some of the 72 counties in six states that share the 1,000-mile river’s shoreline. I came away from that project, and from reporting this year on the energy boom upriver, with the clear conviction that an important American story was unfolding in Ohio River communities that was not receiving the attention it merited.

It seems to me, in short, that the Ohio River Valley is a new nexus where urban leadership, new governing strategies, manufacturing technology, transportation, environmental quality, and energy development are intersecting with increasing momentum and national economic relevance.

This, of course, is not a new role for the river. The Ohio River Valley was a highway to the developing Midwest and West, a liberty line used by slaves escaping from the South to the North, a source of water, resources, and transport for the industrialization that built 20th century America.

It’s just that during most of the last two generations the Ohio River Valley was warped by deindustrialization, disinvestment, depopulation, and all manner of economic and environmental deterioration. I recall, vividly, the days I spent upriver in East Liverpool, Ohio in the early 1990s when just about the only new industrial facility under construction along the entire river was a toxic waste incinerator next door to an elementary school.

That era of decay is rapidly giving way to a new age of dynamism in the Ohio River’s big cities, and new economic opportunities in many of the smaller communities and rural counties. The Owensboro story, told in What’s Done, What’s Next: A Civic Pact, is emblematic of the river’s new narrative. In Owensboro, trends in improving environmental quality, land use, educational investment, research and innovation, parks and recreation, energy use and development, high tech manufacturing, and rising farm commodity values are leading to a better place to live and do business.

Though the influencing factors differ from place to place, much the same story is unfolding all along the river. Warrick County, Indiana is growing, in large part due to its stronger export oriented farm sector, and lower energy costs. Pittsburgh’s universities are global leaders in high-tech research and bio-tech development. The University of Louisville is a health research leader and medical provider, among other accomplishments, and Jefferson County is growing at a faster rate than at any time in the last 50 years.

There are, to be sure, plenty of negatives, too, like the joblessness and poverty that linger from the age of industrial obsolescence that came to characterize the Ohio River as the nation’s rust belt. As I wrote in a March 20, 2012 ModeShift blog post, for two generations few places so darkly illustrated the erosion in American industrial vitality, and the heart sore circumstances of its people, than the upper Ohio River Valley. The 145 miles of river from Pittsburgh to Marietta, strikingly beautiful as it flowed past rounded hills, also drained a landscape of shuttered plants, broken towns, and lives bent by lost jobs and frantic worry. Sociologists and historians episodically descended on one river town or another to study the choices people made to stay, or to go. Journalists also came, treating the valley as a prime specimen in the nation’s laboratory of ruin.

New investment and economic vitality is eclipsing that era. In its place is emerging a new period of promise. That story has not been told in any substantive way. Much of the literature of the Ohio River Valley either preserves it in the amber of its westward influence, or the smoky glory of its early 20th century industrialization.

Now a fortunate convergence of new governing strategies and economic tools are producing a new era of prosperity in the Ohio River Valley. Those very same ideas — developed and executed out of the spotlight in the heart of the country — arguably have as much importance to the nation’s capacity to thrive as Silicon Valley, the energy production alley of the Rocky Mountain West, or the Boston to New York financial corridor.

— Keith Schneider

One thought on “Ohio River Valley’s Story of Recovery”