SALT LAKE CITY — January was supposed to be a great month for Interior Secretary Ryan Keith Zinke, the tall, cowboy-fit, decorated SEAL warrior dispatched by the White House to battle the “elites†and elevate resource development to the primary goal of the world’s largest conservation agency.

Guided by his personal hero, Teddy Roosevelt, who once said “conservation means development as much as it does protection,†Zinke opened the year with the most ambitious federal plan ever to explore for oil and gas off nearly every mile of U.S. coastline. Ten months in the making, the drilling scheme was the latest of the administration’s coordinated steps to sweep away decades of environmental impediments and unleash the fossil energy reserves stored beneath much of the 1.7 billion acres of ocean bottom and at least half of the 500 million acres of surface land overseen by the 168-year-old department.

The bid to decorate America’s coast with drilling rigs was bigger than even the ocean leasing program proposed in 1982 by James Watt, the last Interior secretary to try as hard as Zinke to swing the department’s mission from conservation to extraction. “We’re embarking on a new path for energy dominance in America,” Zinke declared. “We are going to become the strongest energy superpower.”

But five days later, like the unpredictable president he serves, Zinke disrupted the show. During a trip to meet with Rick Scott, the Florida Republican governor and likely Senate candidate, Zinke announced he was excusing the offshore waters of the Sunshine State from participation. The drilling waiver, which shocked his own staff, ignited an impassioned political backlash led by Republican coastal state governors, Congress members, and state lawmakers. It also put the entire plan in grave legal peril because at the very least the federal Administrative Procedure Act requires a substantive and rational basis for making new policy.

The public dismay grew more intense two weeks later when a senior Interior executive rebuked his boss and told a Congressional committee that Zinke’s waiver had no authority. Florida, he said, was still in the offshore drilling plan. As the month ended, Zinke appeared on CNN to counter his aide and explain that the exemption stood because, in Florida, “the coastal currents are different.â€

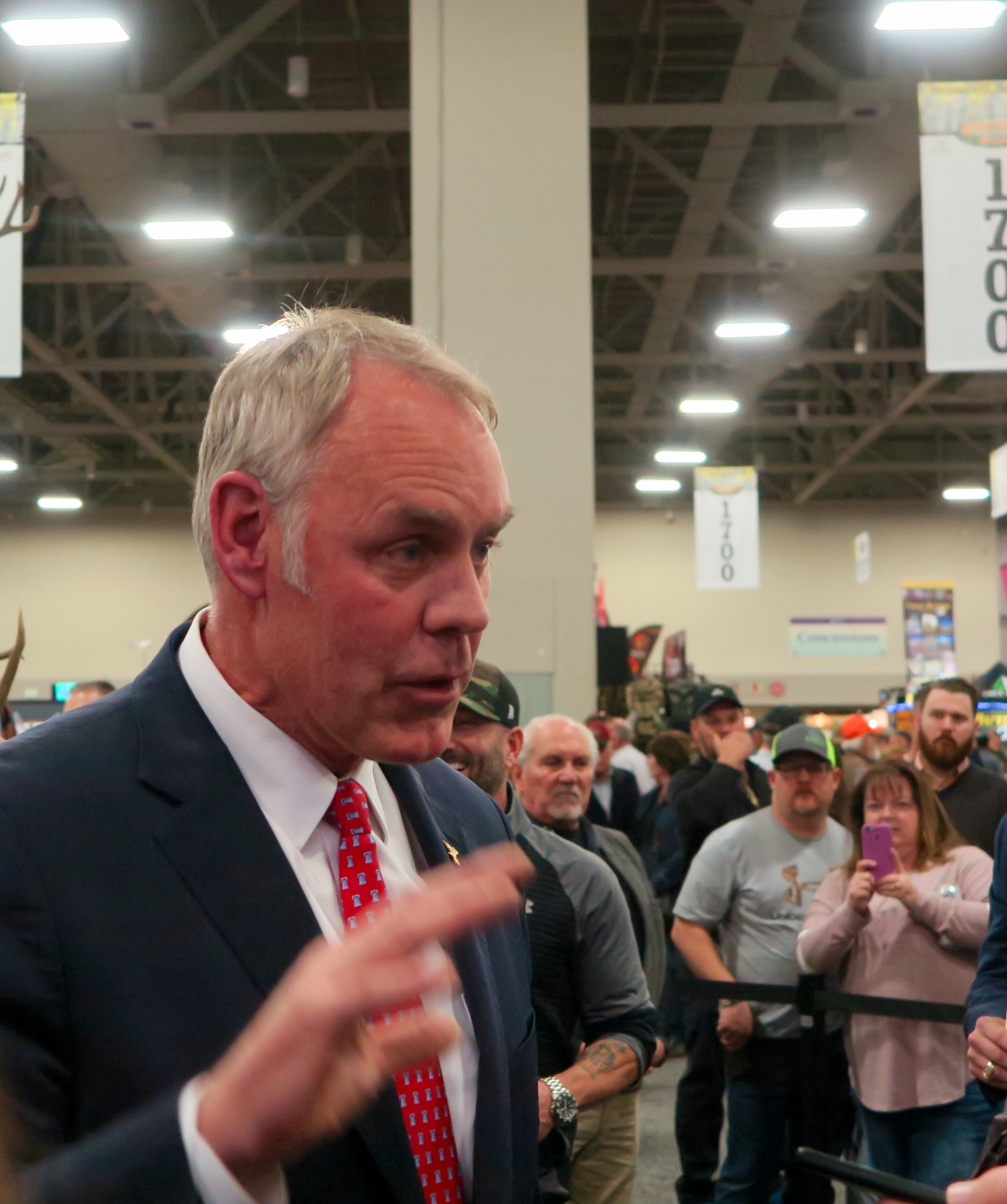

It is not clear why Zinke apparently set out on his own to alter the Trump administration’s marquee energy development plan. Heather Swift, Zinke’s spokesperson, declined repeated requests to interview the secretary or members of his senior staff. “The secretary is unavailable,†she said during Zinke’s appearance at a hunter and sportsmen expo in Salt Lake City.

Whatever the cause, Zinke’s change of heart about Florida raised eyebrows across official Washington. “It was different, to be sure,†said Idaho Republican Representative Mike Simpson.

A Seconbd Year Starts Uncertainly

Until that moment the self-assured Montana favorite son had overcome nagging questions about his judgment and ridden fierce ambition and a sterling resume of public service to the summit of political influence. Along with Energy Secretary Rick Perry and EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, the 56-year-old Interior secretary had emerged as a commander in the president’s triad of cabinet members charged with an uncommonly difficult and divisive objective. President Trump had charged them with breaking through barriers of market trends, law, and climate-related chaos to keep the U.S. economy fixed to a 21st century path to produce more oil and coal, the fading fuels of the 20th.

The steps Zinke has taken to secure that target include first-of-their-kind actions by an Interior secretary. Zinke ended scientific programs to understand the effects of climate change on Interior lands, and forced many of the department’s climate scientists from prominent research posts. Rules to make ocean drilling safer, developed by a bipartisan commission and Congress following the Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill eight years ago, were scrapped. So were Obama-era onshore rules to safeguard air and water from fracking. Zinke weakened the 100-year-old migratory bird protection law so that oil and gas drillers are not prosecuted for all the raptors and waterfowl that drown or are poisoned in their wastewater pits.

Though the President promised “a truly representative process, one that listens to the local communities that know the land the best and that cherishes the land the most,” Zinke dismantled the state and local groups helping to develop ecologically sensitive practices to protect game birds, endangered species, and sensitive areas from energy development.

There’s more. Zinke delivered recommendations to the president that tested the authority of the 1906 Antiquities Act and removed 2 million acres of protected land from two Utah national monuments, the largest withdrawal of public lands from federal safeguards in U.S. history.

He proposed more than doubling entrance fees to popular national parks, arguing that the extra revenue is needed to address $12 billion in infrastructure maintenance and modernization.

In the last months of one of the most active years by any Interior secretary in history, Zinke began rolling out a plan to completely dissolve state lines and instead reorganize the Interior Department’s 10 units around large regional “eco-basins.†Citing a need to update the agency to assume its contemporary mission, the reorganization follows a military command structure. It would install 13 regional managers around the country to oversee the department’s work. If the plan is approved by the Office of Management and Budget, and Congress, those positions would be among the most powerful appointments in the U.S. government.

“The President promised the American people that their voices would be heard and that we would prioritize American interests, and I’m proud to say that this year the Department of the Interior has made good on those promises,†Zinke said in a year-end statement. “Across the department we are striking the right balance to protect our greatest treasures and also generate the revenue and energy our country needs.â€

Carrying himself in public with a Roosevelt-like swagger, and tilting access to public lands toward industrial developers and rural communities has intensified the contest between what Zinked disdainfully calls the urban “elites†and the rural interests who, he says, “are the best conservationists.†It’s a pitched struggle that has just two sides – Zinke’s ardent allies and his implacable critics.

They Like Him in West

In Salt Lake City, Zinke was greeted with a warm ovation by thousands of hunters and sportsmen. “He understands the concept of local control. People here in Utah know more and take better care of the land than somebody in Washington,†said Troy Justenson, president of Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife, a 7,000-member conservation group based in Salt Lake City.

President Trump is a big fan, too. He commended Zinke, the first Interior Secretary from Montana, during the signing ceremony in Salt Lake City in December to shrink Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments.

“Talk about a very special guy that I made secretary of the Interior. Does he know the interior,†said Trump. “He’s knows it, he loves it. He loves seeing it and riding on it. Ryan Zinke, who truly believes in protecting America — he is protecting America.â€

His critics say they feel betrayed. Native American leaders who shaped the Obama administration’s work to establish the 1.35 million acre Bears Ears National Monument in southeast Utah say they were not consulted when Zinke recommended shrinking the monument to under 230,000 acres.

Executives in the nearly $900 billion outdoor recreation industry recoil at Zinke’s work to shrink national monuments and accelerate oil and gas exploration on public lands across the West. They reject Zinke’s effort to tie his work to Teddy Roosevelt, who established 18 national monuments, 5 national parks, 150 national forests, and conserved 230 million acres of public land.

“We did the research and were supportive of his nomination,“ added Peter Metcalf, founder and former chief executive of Black Diamond, a Salt Lake City recreation equipment maker and a leader the Outdoor Industry Association. “Here’s a guy who likes to hunt some, and rides a horse, and believes in public land. He’s going to be a reasonable guy we can work with. Fast forward a year. We have been grossly disappointed. The guy has been horrific.â€

Charles Wilkinson, a professor of law at the University of Colorado and a prominent authority of western history, called Zinke’s monument boundary changes and aggressive energy development a sharp departure for American public lands management, which has been distinguished by the steadily evolving doctrine of safeguarding exceptional expanses of the national domain and expanding those protections. “It’s a radical act the way this president and Interior secretary have gone after the magnificent American land conservation system,†said Wilkinson. “It’s extraordinarily irresponsible.â€

That the Interior secretary is commanding such attention in and outside Washington comes as no surprise to residents in Montana, where Zinke has been a source of pride and public interest since the late 1970s. The second son and middle of three children, his father was a plumber and small business owner in Whitefish, a northwest Montana timber and tourist town near Glacier National Park. A fifth generation descendant of pioneers, Zinke’s grandfather during the Depression helped build the Fort Peck Dam on the Missouri River, one of the nation’s largest.

Background in Montana

As a kid, Zinke’s hometown held 3,700 residents. His grandparents lived nearby and military veterans were around and active. His parents divorced when he was 9. His mother remarried a dentist who was a Marine veteran of the Korean War and had three children. The big family broke up five years later when the couple divorced. “Doc ended up remarrying and I remain close to him today,†he writes in “American Commander,†the 2016 autobiography he coauthored with Scott McEwen. “Why not? He was a Marine.â€

A gifted student and athlete, Zinke was intensely ambitious. Three times he was elected president of his Whitefish High School class. He was an all-state sprinter, and as the star strong safety and captain he led the Bulldogs football team to their 1979 state championship. On the full scholarship he earned to the University of Oregon, Zinke studied geology and played football as an undersized offensive lineman. In 1983 he was named as a member of the All Pac-10 Academic Award team, an honor that recognized him as a scholar and skilled athlete.

Zinke graduated with a degree in geology and planned a career in underwater geology. While attending a game as a former player, Zinke met a two-star admiral who learned about his interest in diving and suggested he attend Navy Officer Candidate School en route to a career in the elite and demanding Navy SEALs.

It was a perfect fit. He earned his officer’s commission in May 1985, thrived in the arduous and unforgiving SEAL training regimen, and joined his first SEAL team in August 1986. During the course of his 23-year career he served in over 60 countries, participated in 300 combat missions, and spent time training SEAL teams. He was promoted to the rank of Navy SEAL Commander and retired seven years later. His 30 medals and decorations include two Bronze Stars for meritorious service.

A year later he began adding the political branches to his presidential timber. He successfully campaigned for a state Senate seat, which he held for two terms. In 2014, Zinke was elected to Congress.

At home, his wife, Lola, and his three children describe Zinke as a devoted husband and father and a skilled outdoorsman. One of the delights of his personal and professional identity is that his daughter Jennifer is a Navy diver married to a SEAL.

Zinke, a first term congressman, supported the president during the 2016 campaign. He solidified his standing as a potential cabinet member with the help of Montana’s junior Republican Senator Steve Daines and Donald Trump Jr., a dedicated big game hunter.

A veteran enamored of military pomp and ceremony, Zinke cultivates visible symbols of his authority and his humanity. He famously rode a horse to his first day on the job and regularly rides in Virginia with members of the National Park Service mounted police. Early in his tenure Zinke expressed a desire to redesign the department flag and ordered his official secretarial flag raised above the Interior headquarters building when he’s in the Washington office.

Mirth

Last spring Zinke established “doggy days†on several Fridays in May and October to encourage Interior employees to bring their dogs to work, including Ragnar, his 10-pound, fluffy, 3-year-old Havanese. “Opening the door each evening and seeing him running at me is one of the highlights of my day,†Zinke said in an email message to Interior staff.

The gesture was intended to improve morale in an agency unsettled by sudden reassignments of senior executives and demotions of climate scientists. Zinke’s chatty Twitter feed includes pictures of Ragnar skipping around the stately oak-paneled secretary’s office with its working fireplace. In the background are some of the assorted big game trophies, including a grizzly bear, called up from the Fish and Wildlife Service’s collection.

Lawmakers of both parties that work with him say Zinke is keenly intelligent, personable, and possesses an engaging wit. When he met with president-elect in December 2016 to discuss a place in the new administration, Trump initially mentioned the Department of Veteran Affairs. Zinke told the president elect: “I don’t think you hate me that much.â€

————————————-

The department Zinke leads is huge. The agency’s $12 billion budget funds 10 major divisions including 417 units of the National Park Service, and 562 wildlife refuges overseen by the Fish and Wildlife Service. The Bureau of Land Management manages nearly 250 million acres of public lands. The Bureau of Reclamation operates 492 dams and 338 reservoirs. The Bureau of Indian Affairs assists the nation’s 567 tribes in management and economic development. The department’s roughly 70,000 employees work from about 2,400 offices nationwide.

Interior owns large reserves of the nation’s mineral, timber, and energy bounty. Roughly 2.1 million barrels of oil pour daily from wells on federal land and in the controlled waters of the Gulf of Mexico, 21 percent of national production.

Now comes year two for Zinke, the season of pushback and powerful impediments formed by an ideological contest for the land that President Roosevelt defined this way: “I recognize the right and duty of this generation to develop and use the natural resources of our land. I do not recognize the right to waste them, or to rob, by wasteful use, the generations that come after us.”

Though Zinke strides confidently through gatherings of allies, smiling and shaking hands, the tallest and best dressed man in the room, the barriers to opening the range man to industrial development are formidable.

The first is Federal law. Environmental groups, Native American tribes, and other opponents have filed dozens of lawsuits to convince federal jurists that the administration’s assault on existing regulations and procedure is illegal. The Natural Resources Defense Council, for instance, one of the country’s largest environmental organizations, has filed 45 lawsuits against the administration, ten of them challenging the Interior Department.

“It’s not good enough in court to say, ‘Hey, we won the election so everything gets changed,†said Michael Blumm, a professor of law at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. “These processes go forward under the Administrative Procedures Act. If you want to make changes, it has to be rational. They have to prove that big mistakes were made in the existing policy that weren’t rational.â€

The second impediment is soft fuel and commodity markets, which are discouraging energy and mineral companies from leasing most of the public land Zinke is making available for development.

Even after the department cleared the way for new coal mines, production on federal land is falling, according to the Energy Information Administration, a statistics unit of the Department of Energy. Though Zinke cleared uranium mining bans from millions of acres of public land around the Grand Canyon and southeast Utah, no company has sought a permit. Uranium prices are 85 percent lower than they were in 2007.

The story with oil is better but not by much. Zinke cites as an early success the $316.2 million the department earned in 2017 from leasing public lands for exploration. That was 61% higher than the $196.7 million that the government made from leasing in 2016.

Leasing Trouble

The bulk of the money, though, was earned in a handful of regions already thick with production wells. The rest of the millions of acres offered for lease were largely ignored by developers, even in Alaska.

A big auction of oil and gas leases in August across 76 million acres of the Gulf of Mexico attracted just 99 bids on 508,096 acres for $121.14 million, or $24 an acre. Compare that to the interest at the peak of oil prices a decade ago. One auction in October 2007 earned the government $5.7 billion. Another a year later earned $5.24 billion, according to department figures.

A third impediment is the expansive agenda of change. The Florida incident is evidence that the Interior secretary may not have the management skills to carry it out.“The execution of these big plans is just not that good,†said Tom Udall, a Democratic Senator from New Mexico, and the son of Stewart Udall, who served as Interior secretary under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. “He had a national plan to open all the offshore. They took action to do that and ran into political issues. So they take it off the table. You can’t proceed down a legal road like that.â€

Still, President Trump has assigned Zinke to leverage Interior to support “American energy dominance,†a fossil-fueled development strategy that other major nations are abandoning. He is doing so by withdrawing or enfeebling environmental measures set in place by every president since George H.W. Bush to fostered more sensitive uses of land, water, and resources as a foundation of the emerging 21st century economy.

The greener way forward before Trump anticipated the dire scientific warnings about climate change, the global pivot away from coal, and the rapid development of renewable energy around the world.

The green ethic also was an important part of Zinke’s social and political persona before joining Trump’s cabinet. As a Montana state senator he drove a high mileage electric hybrid Toyota Prius and earned the highest conservation voter scores ever awarded to a Republican state lawmaker. His nomination for Interior secretary was championed by Outside Magazine, a passionate defender of environmental values, which called Zinke “the last hope for our public lands.â€

When he appeared for his Senate confirmation hearing 13 months ago, Zinke sounded like a reasoned defender of land and water. “I fully recognize and appreciate that there are lands that deserve special recognition and are better managed under the John Muir model of wilderness, where man is more of an observer than an active participant,†he said.

During the hearing, Zinke departed from the president’s view that climate change is a hoax. Noting his experience in Glacier National Park, where 85 percent of the glaciers have vanished, he told the panel, “When my family and I have eaten lunch on Grinnell Glacier, the glacier has receded during lunch. Climate is changing. Man is an influence. I think where there’s debate on it is what that influence is, what we can do about it.”

He assured the Senate panel that like his hero Rosevelt he would marry development to national environmental values.

“Those two are not mutually exclusive,†said Rep. Bishop. “Zinke believes we can have multiple uses and protect the environment. It’s not a one or the other type of question. If you know Zinke as well as I do there is probably nobody in the world more concerned about preserving our natural resources.â€

—————–

There is a calculated, deliberate, instinctive quality to how Zinke has managed the department and his life of personal and professional achievement. In “American Commander,†Zinke recounts lessons he drew from several pivot points.

His grandmother, he writes, influenced his “social Libertarian values.†She was self-reliant, frugal, hardworking, and believed that charity should be a role played by the government, he writes. “I believe there is a role for government,†Zinke writes, “but the role is limited, very limited. In general, unless it involves abuse of small children, the elderly, or the unfortunate, the government should stop at your mailbox.â€

His SEAL experience informed his expertise in national security and his loathing of bureaucrats and “desk jockeys†far from the front lines who get in the way of sound ideas.

Zinke’s geology degree, earned at the University of Oregon, is another ingredient in a worldview that puts fossil fuel production and energy independence as essential elements of American security and prosperity. “The alternative is to continue to be held hostage to foreign oil and gas-producing countries that not only don’t have enforceable environmental standards, but are frequently our enemies,†he writes.

The secretary, though, did not help move those views ahead when he waived Florida from the offshore drilling program. That misstep is the most recent in a pattern of indulgence and self-destructive decisions that affected his 23-year military career and trail him at Interior.

Midway through his turn as a decorated SEAL leader, Zinke was cited in 1999 for improperly billing the Navy for personal travel. An unfavorable fitness report signed by a vice admiral cited Zinke’s “lapses in judgment,†and temporarily blocked his promotion to Navy SEAL commander, which he earned in 2001.

Zinke reimbursed the Navy for $211 and asserts that the incident is a “glitch†in his life.

Zinke’s travel expenses also have prompted scrutiny from the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General and the agency’s Special Counsel. They are investigating an expensive chartered flight he took last year to events that may have unlawfully mixed official business and political fundraising for Republican candidates.

In an appearance at the Heritage Foundation late last year, he explained the public attention to his Interior Department flights as a “little b.s.†He added: “”Every time I travel I submit the travel plan to the ethics department that evaluates it line by line to make sure that I am above the law. And I follow the law.â€

Starting With Glitches

Confident that the travel expense issues quieted, Zinke issued this end of year message of confidence about his work: “We ended the war on coal, and we restored millions of acres of public land for traditional multiple use. We expanded access for recreation, hunting and fishing on public lands, and also started looking at new ways to rebuild our national parks. This is just the tip of the iceberg. Next year will be an exciting year for the department and the American people.”

January was supposed to be a great start for Secretary Zinke. Exciting, though not necessarily in the way Zinke envisioned. Mid-month, nine of 12 members resigned in protest from the National Park System Advisory Board, an appointed and nonpartisan group established 83 years ago to consult on department operations and practices.

The group expressed the same complaint heard from many conservation, environmental, and advisory organizations since Zinke took office. The secretary had surrounded himself with a select group of aides and was reluctant to open that tight circle to interests other than energy, mining, and industrial interests. Logs of the secretary’s meetings that have been made public confirm the complaint.

On January 24, California filed a lawsuit against the Interior Department over its plan to scrap rules established by the Obama administration to make fracking on public lands safer. “The rules have to go through a process,†said Xavier Beccera, the Democratic California Attorney General. “You can’t just unwind them by fiat.â€

Days later, attorneys general from twelve coastal states also signed a letter that promised they would sue the Interior Department if Zinke did not cancel the offshore drilling plan. “We’re going to do everything we possibly can to stop it,†said the letter.

A flurry of news reports in January also buffeted Zinke by highlighting the secretary’s travel spending patterns and investments. Zinke cost taxpayers more than $6,000 for a helicopter trip to Virginia to ride a horse with Vice President Pence. Newsweek reported that Zinke spent nearly $40,000 from a wildfire preparedness fund to pay for other flights, expenditures confirmed by the secretary’s office. Zinke dismissed criticism that he was misusing funds as “a wild departure from reality.â€

Huffington Post reported that Zinke did not disclose stock he owned in PROOF Research, a Whitefish weapons company. Heather Swift, Zinke’s spokesperson, said the shares were valued at less $500 and did not have to be reported.

And critics are suspicious about another hometown company, tiny Whitefish Energy, which gained a non-competitive $300 million contract last year to rewire Puerto Rico’s hurricane-wrecked transmission grid. Zinke told Fox News that his only connection to the company is his son, who worked for a time as a Whitefish Energy flagman. “I didn’t have any influence. Didn’t have any knowledge of the contract,†he said.

Whether any of these events affect Zinke’s standing in the administration is unknown. History indicates that overreaching on offshore drilling has political costs. In 1983, a year after Secretary Watt proposed his big plan he was forced out of his Interior post.

There are indications that Zinke’s natural constituency is not happy. In January 1,200 veterans, members of the conservative American Monuments Alliance, issued a letter to Trump and Zinke that urged the administration to withdraw its plan to shrink national monument boundaries.

“The value of our public lands has been woven into the songs and stories of our nation since its founding,†wrote the veterans. “We need your help to do our duty to preserve that greatness in honor of all who came before us and for the benefit of all who will come after.â€

Colorado College’s respected Conservation in the West opinion survey, made public in January, found that among the 3,200 voters in 8 western states that were polled, just 38 percent approved of Zinke’s oversight of land, water, and wildlife. Two thirds of those polled found the decision to shrink Bear Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in Utah a “bad idea.â€

Minke’s departmental reorganization plan is running into serious political opposition from rural conservative leaders. On February 1 roughly 50 rural county officials from three western states met in Utah with a senior Interior Department official to discuss the reorganization. The county commissioners from Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming did not like what they heard.

“The consensus in the room was not favorable,†said Demar Dahl, a cattle rancher and commissioner in Elko County, Nevada, who attended the meeting. “My county in Nevada would be in the same eco-region as Los Angeles. They don’t have anything in common. Who do we work with on a state issue if our regional headquarters is in Salt Lake? It’s a bad idea.â€

Zinke’s public lands decisions are now forming a record of action that could affect his political prospects following the Trump administration. “He’s changed,†said Land Tawney, president and chief executive of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a Missoula-based sportsmen’s group with more than 18,000 members that endorsed Zinke’s nomination for Interior secretary. “In Montana being anti-conservation won’t get you very far. Watch how that diminishes his support if he runs for governor or the Senate. If he continues on the path he is on now people are not going to vote for him.â€

An expert strategist, Zinke recognizes the weakness on his flank. He’s putting the more familiar Roosevelt conservation ethic to work in Montana. He banned gold mining from public lands near Yellowstone National Park. And in the same report that led to much smaller boundaries for Bears Ears and Grand Staircase, Zinke proposed a new national monument. It’s the 130,000-acre Badger-Two Medicine Area in northwestern Montana, near the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and a three hour drive from his home in Whitefish.

As Roosevelt dclared: “Of all the questions which can come before this nation, short of the actual preservation of its existence in a great war, there is none which compares in importance with the great central task of leaving this land even a better land for our descendants than it is for us.”

— Keith Schneider