The week leading up to April 19 is turning out to be a gruesome one for the United States. On April 19, 1995 Timothy McVeigh blew up the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, and injuring 680. That attack, McVeigh said, was justified by the FBI assault two years earlier, April 19, 1993, on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. Seventy-six people died.

Waco and Oklahoma City crystalized menace in several new dimensions in the United States. The scale of the deaths in Texas, and the mortal focus on the calendar and commemoration in Oklahoma, illustrated a joining of wickedness and fanaticism rarely encountered in the country.

Yesterday’s Boston Marathon bombing unveiled another facet of evil. The idea that someone planned to maim and kill the innocent, perhaps even purposely aiming to blow off bystanders’ legs on a day focused on a long run, displays a vicious cunning designed to formalize the “at any moment” nature of big public gatherings in the United States that have steadily become more nervous.

You have to wonder whether the April 15 date was a factor. Over the last generation the third week of April has become a stage for escalating mayhem in the United States.

On April 20, 1999 two students at Columbine High School in Colorado murdered 12 classmates, a teacher, and killed themselves. Twenty-four people were injured.

On April 16, 2007 a student at Virginia Tech killed 32 people, wounded 17, and killed himself.

The Boston Marathon bombing occurred on the day race organizers honored and remembered the 20 children and six adults who were killed in an elementary school in Newtown, Conn. That day the shooter also killed his mother and himself. And no accounting of the recent list of horribles should omit the 12 people killed and 58 injured last July in an Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting. Or, for that matter, 9/11.

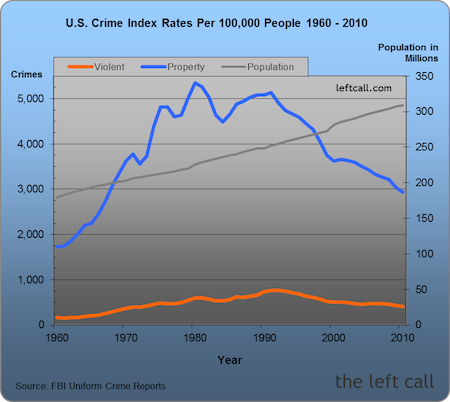

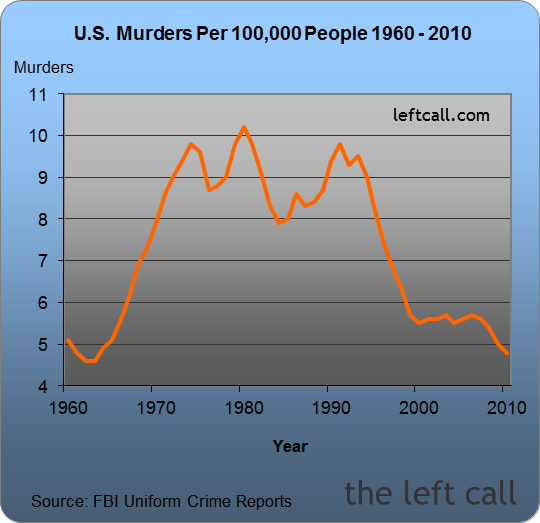

The pathology of violence, the determination to disrupt, the focus on turning the public space into a gallery of blood; that all seems plainly evident. But why have these killings occurred over the last generation, a period when other statistics show America is getting safer? Deaths from traffic accidents are way down. Rates of violent crime have declined dramatically since the peak years of the 1970s and early 1980s. Rates of murder are the lowest they’ve been since the 1960s. See the charts below, which are based on FBI Uniform Crime Statistics.

The gunners and bombers are testing America’s mettle. Our purpose is to be strong, and not let this kind of random bloodletting succeed in convincing Americans that big public gatherings are dangerous, especially during an era of improved personal safety.

— Keith Schneider

Hi Keith,

Something about your summation makes me question whether any conclusions about what the hell is really going on can be culled from just comparing those big numbers. Maybe there is more to learn from looking at who is doing the murders and how and where they are committed.

One recent interesting study is the City of Chicago 2011 Murder Analysis. https://portal.chicagopolice.org/portal/page/portal/ClearPath/News/Statistical%20Reports/Murder%20Reports/MA11.pdf

In the study it also concludes that the murder rate, high in the last years is nothing compared to what it was in 1991 at 928 murders. But there is something more telling in the data. Today far more murder victims are found outdoors than indoors compared to 1990’s figures. In 1991 roughly as many murders took place in residences as they did in public ways. Around 2000 that balance shifted and grew where by 2011 6 times as many murders took place in public ways than in residences.

And murder cases that have been solved by the Chicago police department have steadily gone down from 619 cases out of 928 cases cleared in 1991 to 128 out of 433 cases in 2011. The statistics also show that gang related murders have increased while other categories have remained the same or gone down slightly.

I’m no sociologists but it appears to suggest that violence by those who are disenfranchised or see themselves as such has developed into a more public display. An increase in uninhibited display of violence as opposed to a more personal violent act. If that’s the case, the total murder rate may be down but we should not take to much comfort in feeling safer because of that statistic, if the violence is a more public display.

Richard, interesting conclusion. I didn’t go into the media focused messaging that promotes violence and killing. That, too, appears to be an influence on whether we feel safer or more endangered. It’s been a rotten lousy week, again. Keith

A nation of people who bomb other country’s cities and homes unmercifully and then sit and watch it on tv for entertainment might not be too surprised at a little occasional spillover. But it’s not polite or patriotic to talk about that.

What do you suppose the ratio is, of pounds of explosives we blow up in other peoples’ homeland versus what they blow up in ours? How many millions to one? The smarmy, narcissistic blabber in the media about this incident is nauseating.