RAIPUR, Chhattisgarh, India — This striking nation, with cities full to the brim with people, and a lavish countryside wired together by kidney-jostling roads lined with mango trees, is a treasure of surprises and paradoxes all its own. In nearly a month of travel here, to India’s capital New Delhi, its prime grain-growing states in Punjab and Haryana, and to its second largest coal-producing state in Chhattisgarh, my colleagues and I encountered all sorts of interactions unique to India.

India, for instance, is in the midst of a persuasive transportation infrastructure modernization campaign. It is opening new airports, including one of the newest in this city of 1.2 million people. Most aren’t terribly busy, though. Air travel is affordable just to the upper middle class and wealthy so the modern glass and steel buildings often have nearly as many security, airline, and food service personnel in them as passengers. The consequence is that the process of arrival, security clearance and boarding operates on India time.

This morning, 80 minutes before the scheduled boarding time for our flight to New Delhi, I arrived at the brand new concrete-is-still-setting Raipur airport with Aubrey Parker, my Circle of Blue colleague. Entering the terminal, past armed military guards, requires a print copy of our online tickets. The counter to secure the printout, though, did not open until 7:30 a.m. for an 8:25 boarding time.

No problem. Nobody was in the terminal so once we gained the printout there were no lines at the airline counter for the actual boarding pass, or to clear baggage security. But one more surprise awaited. We were stopped at the entrance to the gate area, where carry-on baggage is searched and passengers are frisked. The guard at the gate said the gate area didn’t open until 8:00 a.m., and directed us to a semi-circle of seats where, we noticed, a couple of dozen other passengers also waited. We giggled.

TII: This is India:

— Cows and dogs. Cows are sacred in India, and so, it very clearly appears, are stray dogs. Both roam freely everywhere. They take up space on city sidewalks, in parks, along rural roads, in gardens and fields and empty lots. Cows and dogs drink from the same polluted streams, eat at the same garbage piles. They slowly amble across the same city boulevards and rutted rural highways. They even lie together, often side by side, in curled clumps. There are so many cows and dogs that after a while you just don’t notice them, unless a cow nudges you out of the way on a street corner, or a dog gets set to pee on your duffel. TII: This is India.

— Women not nearly so sacred. India’s view of women is odd to an American. In cities, men occupy most of the visible workplace positions. Men are the supervisors, the managers, the academics, bureaucrats, hotel housekeepers, waiters, secretaries, cooks, shopkeepers, drivers, police officers, gas station attendants. The rare sectors that feature women are the airline industry, where women serve as flight attendants and ticket agents, the military, where women are very visible among the troops, and in hotels where we saw women at the front desks. In the countryside, women are laborers, mixing cement for road projects, bearing cement and bricks and water on their heads for new buildings. Where we saw women, but talked to very few, were in Indian homes where women ran their households, raised children, and dutifully executed the role of gracious hosts.

— Female babies and young women not sacred at all. The most disturbing facet of Indian culture is the dangerous contempt that the culture holds for baby girls and young women. Almost every day that we were here Indian newspapers published articles of parents murdering or injuring their little girls. The motive is said to be the cost of raising girls or of outlawed dowries in a patriarchal society that prizes male children. In one terrible crime parents in a northern state strangled their handicapped girl, incinerated her body, and buried the remains. In another, parents killed a young woman because, they said, she dishonored them for choosing her own fiancee, not the one they had picked for her arranged marriage. Yesterday a father, engaged in a furious quarrel with his wife aboard a moving bus, threw his two-year-old daughter out the window out of spite. The little girl survived with no injuries, said the report, and the police declined to bring charges.

Delhi, meanwhile, is engulfed in an epidemic of rape that citizens blame on lackadaisical police patrols and lazy rape investigations. This week a 23-year-old medical student was raped by six men aboard a moving bus in Delhi. The suspects have been arrested, and two of them confessed to their participation. The rape prompted a powerful civic pushback, principally by women, who called for a more urgent and credible police response. The protestors noted that nearly 600 rapes have been reported this year in India’s capital. The number of sexual assaults is rising, the streets are unsafe, they said, and that rapists feel empowered because arrests are not made, and courts are lenient.

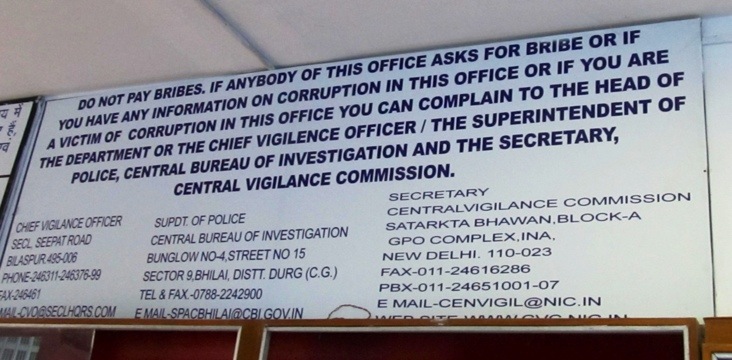

— Chai and pani, tea and water. To be Indian is to know bribery and corruption intimately. It’s an economy and culture so embedded in the Indian way of doing things that to succeed here is to be expert in what many Indians call “tea and water.” That’s the euphemism for an official, a policeman, a ticket agent, a judge, a politician, a business owner, a permit evaluator seeking a bit extra, an off-the-books payment for his morning tea. In my interviews here businessmen and government officials confirmed the pervasiveness of the culture of corruption that is hampering India’s development. They understand that everybody is a suspect. Massive investigations are underway here to uncover and prosecute big corruption scandals involving India’s biggest coal company and Walmart. The little bribery deals go unprosecuted for the most part. In one interview in Raipur, a young lawyer who’s turned to developing a fast-growing grass as biomass to replace coal told me it will take two generations to stamp out corruption. His generation, professionals and tradesmen and women in their 20s and early 30s, have started an internal campaign based on values. The generation behind them, teens and schoolchildren, he argued, will continue the work. The theory is that people in my generation and older will pass on, and with us chai and pani will end.

— Tea, four cups a day. Everywhere we went in India our hosts served tea. At least four cups a day, often served in the sitting rooms of private homes. Indians thrive on grace and hospitality. To deny a host the opportunity to serve the “foreigners” tea in the sanctity of their homes is more than an insult, it prompts real emotion and psychic pain. So we only said no to the invitation once, due to a tight schedule, and ended up going to tea anyway. That occurred in a rice milling town in Punjab. We started our visit to the mill with tea in the home of one of the two brothers that owned the enterprise. The second brother arrived at the mill about half an hour after we did and at the end of the tour insisted, cajoled, pleaded with us to come back to his home for tea. We, unwisely and indecorously, insisted on our Midwest principle of punctuality and repeatedly thanked him while turning away the invitation. In the end he and his brother led our driver, who didn’t know the way back to the highway, through town, stopping in front of the owner’s house. We had tea. We met his wife. We admired the religious shrine that Indians establish in their homes. And we recognized that when in India and tea is offered, drink tea with joy and gratitude at the generosity and curiosity of your hosts.

— Indian children are beautiful. In every city, every town, every village India displays its beautiful children. Grade school kids in uniforms. High schoolers riding bicycles to work. Farm children pumping water. Infants and toddlers in their mothers arms. Urchins sent by their parents to beg in the street. The children across this beautiful and chaotic country are absolutely beautiful. The boys are lean and handsome. The girls are bright-eyed, wary, and lithe. There’s a reason India’s women do so well in the Miss Universe competition, and its men are movie stars and pop idols here and around the world. They are the most stunning individuals in a nation of gorgeous kids.

— Young American woman causes a sensation — everywhere. We met a lot of Indian kids because Aubrey Parker, our tall and pretty assistant editor, attracted a lot of attention from young people wherever we went. In Chandigarh, northern India, teenage boys wanted their pictures taken with Aubrey, and school girls wanted to touch her and shake her hand. At the train station in Raipur, Aubrey was surrounded by older girls and young men in their early 20s, all of whom wanted their picture taken with her. Outside Korba, Aubrey stopped at a street intersection in a busy village, and while she photographed a store front and an interesting road sign people who lived on the second floor of the town’s largest building crowded the veranda to watch. At times they stood three deep. Outside Amikapur, in northern Chhattisgarh, we stopped outside a middle school. When Aubrey stepped outside the car the school erupted. Kids crowded the open windows, giggling and pointing and talking in a tempest of interest. We briefly entered a home next door for tea and within minutes we heard the rush of stampeding feet. The teacher, apparently unable to quell the disturbance, had let the kids out of school. About three dozen kids, all about 12 or 13, had run to the house to get closer to Aubrey. The boys were mute while the girls asked simple questions — Where are you from? What do you do? We were told that few Americans traveled in the places that we visited, and fewer still were young American women. Aubrey told me that the attention wore her out a little bit. She never showed it. And that’s a big reason why Aubrey’s wholesome Midwestern looks, her friendly demeanor, her knowing eyes and bright smile, and her grace and patience proved irresistible in India.

— Mad traffic. If you ever travel overland by car in India get a driver. Traffic is horrendously heavy in India’s cities, and dangerous on the rutted two-lane terror strips that serve as India’s highways. Following in the tradition and practice of British motoring, drivers pilot from the right side of the vehicle and traffic moves in the opposite direction from American traffic. The more important threat for Americans is that Indian drivers are mad. They know but don’t respect the decorum of lanes, traffic signals, the protocols of passing and speed limits the way most American drivers do. Here a two-lane highway often becomes a defacto four-lane highway as cars and trucks and buses speed toward each other, just managing to squeeze back into lane to avoid crashing. Animals and scooters and pedestrians take up space on the sides of highways, which means that wandering to the shoulder to avoid a crash is impossible unless drivers are willing to kill innocents. Bus drivers are the worst. Their vehicles are powerful and fast enough to accelerate and pass slower moving vehicles. And they are big enough to intimidate. So with their annoying animal scream horns sounding irritating warnings, buses careen down India’s highways, weaving in and out of their lanes, daring oncoming traffic, a kind of duel for road supremacy that once in awhile fails to cheat death.

— Food is great. I’m not a big supporter of heavily spiced food. But I love Indian cuisine. I’ll eat dal — a spiced sauced dish in various iterations and flavors — with garlic nan — a chewy flatbread — any time. We generally ate twice a day on this trip and while I was unable to pronounce almost all of what I was served, and couldn’t remember their names, there was barely a single dish that I wouldn’t have again.

— 11 East Nizamuddin is a Delhi refuge. If you’re coming to New Delhi the place to get acclimated during the trip’s first days is Ajay Anandd’s bed and breakfast at 11 East Nizamuddin — Neez-uh-moo-deene. Breakfasts are good. Rooms are comfortable, clean, and reasonably priced with splendid baths. Internet works well. Each room comes with a cell phone because it’s so onerous — national security we are told — for foreigners to obtain Sim cards here. The bed and breakfast is well-located in the city. And Ajay is a warm and patient man who takes care of his guests. He’s been so helpful in guiding us to obtain train tickets, the use of three-wheeled Tuk-Tuks to get around, and developing other resources. Email is ajay.anandd@elevendelhi.com. Web site is elevendelhi.com.

— Keith Schneider

Your descriptions of India are as vivid and colorful as the scenes you depict.

wow wonder article buddy keep it up.