By Saturday, as the deep freeze lifted and temperatures across Texas warmed to near normal for this time of year, water poured from broken lines beneath streets. Fountains of water sprayed from valves and cracks in building exteriors. Indoor waterfalls spilled from caved-in ceilings in schools and homes and hospitals. Homeowners gathered up the last remnants of melting snow and stored them in buckets and bathtubs.

“Where do you want to start?†said Ty Edwards, general manager of the Middle Pecos Groundwater Conservation District in Fort Stockton. Edwards explained why the power outages across the state triggered a water crisis.

“Utilities went down because even though they have generators, the generators won’t start when it’s 3 degrees,†said Edwards, who noted that Big Lake, a small town of 3,200 residents east of Stockton, ran out of water because its reservoir was completely drained, its water storage tank was dry, and the town’s well field stopped operating when pumps failed.

“In my house, we were without water and electricity for 70 hours,†Edwards continued. “We slept in front of the fireplace and used bottled water. I have three kids — 7, 9, and 13. We roasted hot dogs on the fire and ate s’mores one night. The whole town is going through this.â€

Among the places on Earth that best know calamity born of severe ecological disruption, Texas ranks near the top. In 2011, an earlier deep freeze caused blackouts. That same year, Texas was ripped by a harsh drought that wrecked crops and caused panics over water shortages. In 2017, a hurricane drowned Houston.

Still, as power outages, water scarcity, and cold battered all of the state’s 254 counties, the absurdity and danger of the latest emergency appeared to hit Texans with more weight and urgency than any other. One reason is that the deep freeze featured multiple crises that unfolded simultaneously: heavy snow and single-digit temperatures paralyzed cities and cost at least 30 lives, according to the latest tally; utilities failed all over Texas, leaving at least 4 million people in the dark and several million without reliable water service; and the Covid-19 pandemic killed more than 700 Texans last week.

On Saturday, President Joe Biden declared a major disaster, making federal funds available for relief in Texas and two more states affected by the freeze –Oklahoma and Louisiana. “Assistance can include grants for temporary housing and home repairs, low-cost loans to cover uninsured property losses, and other programs to help individuals and business owners recover from the effects of the disaster,” said a statement from the White House.

Even as the snow melted and the lights flashed back on late in the week, the harshest and most lingering lessons emerged, all of them expressed through the essential element that Americans take for granted: clean water. Thousands of Texans broke their pandemic safety bubbles to invite marooned friends and family into their warmer homes, though many had no running water for handwashing. It will be two weeks before Texans know whether such generosity will cause more Covid-related cases and deaths.

It wasn’t a matter of scarcity. Water was everywhere. Undrinkable water dripped from faucets. Texans drew water from swimming pools and collected it from streams and lakes. Where bottled water was available, buyers bought it by the case and hauled it home on foot.

Rather, like so many billions of people around the world, what Texans encountered after the lights turned on was unsparing difficulty in gaining access to clean water. Though it occurred in some of the world’s wealthiest cities and most exclusive suburbs, the image of Texans scavenging for water was hardly different in its basic form and drama than what occurs daily in rural India and Kenya.

Everybody in Texas has a story. “We didn’t lose power but we lost water in part of the house,†said Michael Young, a research scientist at the Bureau of Economic Geology, a University of Texas research organization, who lives in Austin. “Pipes froze downstairs and we thawed them out carefully. We got water running again. Not hot water, though. We just have to wait until temperatures rise to see if any real damage occurred.â€

Young also reported that apartment buildings all over Austin lost water. He invited two friends who lived in apartments to stay in his house. “We have four adults and seven dogs in the house now. This is happening all over the city.â€

Low-income families and the elderly were particularly burdened. Electrical and water infrastructure are not nearly as stout in low-income communities as they are in wealthy neighborhoods. Marleny Almendarez, a single mother of two who lives in a Dallas home with five other people who lost water and power, sheltered her family in a bus that the city set up as a warming station. After a year of joblessness for the adults and disease that affected every member of the household, Almendarez told the Texas Tribune: “It has been infinite sadness. Many people have lost their jobs, have lost relatives. You feel helpless, not being able to do anything.â€

Just as scientific models predicted, ruinous meteorological events in Texas – rain, wind, droughts, floods – now occur with much greater intensity. There is a theory, being hashed out in peer-reviewed journal articles, that the deep freeze that leaked cold air into the state last week is the product of a warming Arctic and a more unstable jet stream. Testing that theory is the object of intense scientific scrutiny and robust debate, but the trend of more severe weather is clearer in the Earth’s other high-energy and unstable climate-affected zones.

Californians contend with deeper droughts, hotter wildfires, mudslides, and earthquakes. Glaciers are melting in India’s Himalayan states, causing deadly floods. Australia’s Murray-Darling basin nearly dried up from 2002 to 2010, and fires now routinely ravage coastal highlands. China’s Yellow River Basin is steadily drying.

In each of these regions residents and lawmakers started to develop collective responses. California embraced new water policies and seeks change in urban land use and forest management. India curtailed its Himalayan hydropower development. Australian states reversed course and allowed the federal government to manage water supply and irrigation. China enacted quotas on how much water provinces could draw from the Yellow River.

The question Texans face is whether to continue electing lawmakers who ignore the consequences of climate disruption, which many state leaders consider a scientific hoax. Mid-week, Gov. Greg Abbott, following the lead of the state’s powerful fossil fuel and utility sectors, falsely asserted that the power outages were caused by frozen wind turbines. The unfounded attack, amplified by Fox News and reactionary Congressional legislators, was specifically intended to weaken state and national support for a renewable technology that is helping to slow climate change.

The blackouts were not caused by wind energy, which typically supplies 10 to 15 percent of total demand in the winter. The primary culprit was competition for natural gas between utilities and homeowners, and transmission and distribution networks that froze and failed to deliver their goods. Gas accounts for about half of the state’s 90,000 megawatts of electrical generation capacity; coal and nuclear contribute around 27 percent of capacity. Texas lost some 45,000 megawatts of power, more than enough to cause power outages that lasted for days.

The same problem occurred during a cold snap a decade ago. But state authorities declined to require gas suppliers or utilities to weatherize their equipment. And Texas operates an electrical transmission grid that embodies the state’s go-it-alone spirit and distrust of federal regulation. Most of the state is served by the Texas grid, which is not connected to transmission networks beyond its borders. Even if they wanted, utilities could not secure any power from other states.

“Folks I’ve talked with point to poor weatherizing of equipment, wind included, leading to multiple systems failure,†said Young of the Bureau of Economic Geology. “Private utilities that generate electricity are making decisions based on probabilities of these types of weather events and the cost to protect systems that insure against them. We can see how the systems reacted during this low probability event.â€

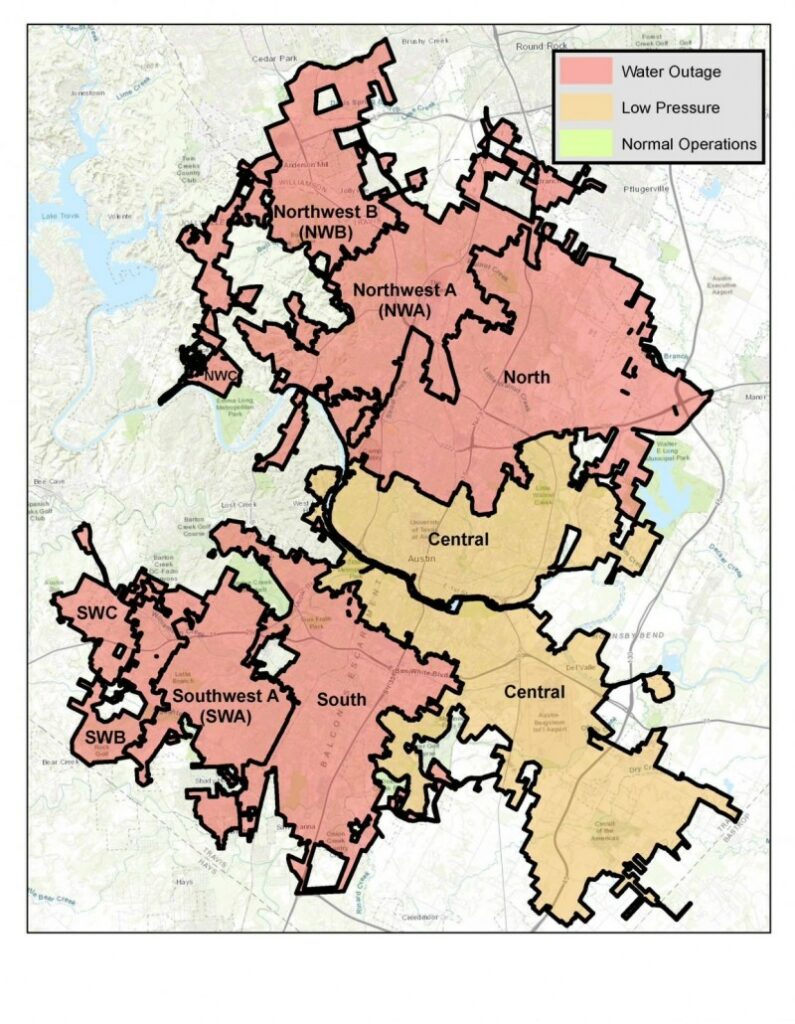

Here’s what happens in Texas when nature so easily overwhelms years of poor decisions. As the week ended, more than 1,100 of Texas’s 7,000 water utilities alerted their customers to boil their water. Almost half of the state’s 29 million residents were affected.

There was no running water in much of Austin. In San Antonio, water was shut off to 30 percent of the city. A big apartment development in San Antonio burned to the ground because fire hydrants were inoperable.

Many small cities were unable to supply water to all or a portion of their customers. San Angelo, a West Texas city of 100,000 residents, alerted residents through its Twitter feed that water trucks would deliver to neighborhoods until 10 p.m. nightly. “They will start back up tomorrow morning to go by areas that they were not able to get to tonight,†the city said. “We ask residents to either leave their containers out or place them early tomorrow so that they can be filled.â€

“A lot of neighborhoods, straight up, don’t have water,†said Sharlene Leurig, an Austin resident and chief executive of Texas Water Trade, a water market research and innovation group. “Has there ever been so many people cut off from water in this country?â€

Likely not. Circle of Blue was not able to identify a comparable statewide disruption in water supply, and especially in the country’s second largest state. The deep freeze and its accompanying electric blackouts, water line breaks, and interior flooding also are bound to produce the largest weather-related financial losses in state history, according to the Insurance Council of Texas. The highest loss to date was the $20 billion in damage (in 2020 dollars) that Hurricane Harvey produced in 2017.

A sizable slice of those damages will unfold along the Gulf Coast, where temperatures were the lowest in 126 years. Scientists said the freeze will lead to a giant fish kill and harm the region’s multi-billion dollar recreation and sport fishing sectors. As waters warm, the extent of the damage will become clearer as tens of thousands of dead speckled trout, red fish, black drum, and all the fish they feed on float to the surface. “It collapsed the food chain from top to bottom,†said Dr. Larry McKinney, former director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, a unit of Texas A&M University in Corpus Christi. “It will be the biggest fish kill we’ve ever seen.â€

Over the weekend water utility executives said they still did not know how long it will take to repair their supply networks – a few more days in some cities, maybe another week or so in others. Executives and government authorities were similarly baffled following extreme weather events in the Himalayas, California, India, Australia and other regions battered by the planet’s 21st-century truculence.

The end to the Texas water crisis is still out of view. When the emergency subsides, though, a seminal question will emerge. Will Texans express the imagination and resolve to reduce the threat from the inevitable next deep freeze, drought, or hurricane?

A version of this article was posted by Circle of Blue on February 21, 2021.

— Keith Schneider