rely on to measure progress in Lake City. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

LAKE CITY, MI – Two facts about Michigan agriculture are scarcely recognized outside the fences and beyond the drainage ditches of the state’s 45,000 farms. The first: farming is among the most technologically sophisticated industrial sectors in Michigan and every other state. Second: livestock farms are the state’s largest source of water pollution from toxic nitrates and phosphorus, and air pollution from methane, a powerful climate change gas.

Here on Michigan State University’s 1,100-acre livestock research farm, technology and pollution prevention have converged in a $19.2 million project that has national implications. The goal: prove the value of advanced cattle production practices to stem environmental damage while simultaneously enhancing farm financial statements.

The five-year, multi-state project, which launched in 2021, is led at M.S.U. by Jason Rowntree,

professor of animal science and the C.S. Mott Endowed Chair of Sustainable Agriculture. Rowntree has devoted his career to studying how rotational grazing systems that move cattle from pasture to pasture reap benefits for water, air, soil, and climate that have largely eluded mainstream agriculture.

“I start with this premise,” Rowntree said in an interview. “Here are the outcomes we need. We want organic matter to improve soil health and build carbon. We want to improve water infiltration to reduce erosion. The rain you get is the rain you keep. We want to increase ground cover. We want to enhance biodiversity.”

All worthy outcomes, but how will livestock producers know if they are being achieved? That’s the gap that Rowntree and his collaborators have identified and are working to fill.

“There really isn’t anything in place that quantifies the outcomes of these implementations,” Rowntree continued. “Not until we can more aptly quantify these outcomes in water, carbon, biodiversity, soil health, and do that on a watershed and state scale, are we going to get our arms around this. That’s the crux of the research here.”

Cattle and Grass

Rowntree’s laboratory spans 570 acres of fenced pastures where a herd of Fido Red Angus cows and calves, a hearty grazing breed from Montana, feed on abundant stands of tall grass. In the last 15 years, Rowntree has turned the MSU farm into a nationally prominent center of environmentally sensitive livestock production practices that also reduce costs and improve farm profitability.

His work has been methodical. When he first arrived at MSU in 2009, Rowntree halted the use of chemical fertilizers and relied instead on manure and nitrogen-fixing legumes — clove and alfalfa — to supply nutrients to pastures thick with tall grass. He and his colleagues build paddocks and move the herd from one to another, essentially mimicking the behavior of American bison or African wildebeest.

The practice allows grasses to grow in abundance and sink deep roots. Keeping the land covered instead of overgrazed allows rain to seep deeper, reduces erosion, and adds organic matter that improves the health and carbon-storing potential of growing plants and soil. Grazing cattle drop fertilizing manure across a pasture, limiting the flow of nitrates and phosphorus into water.

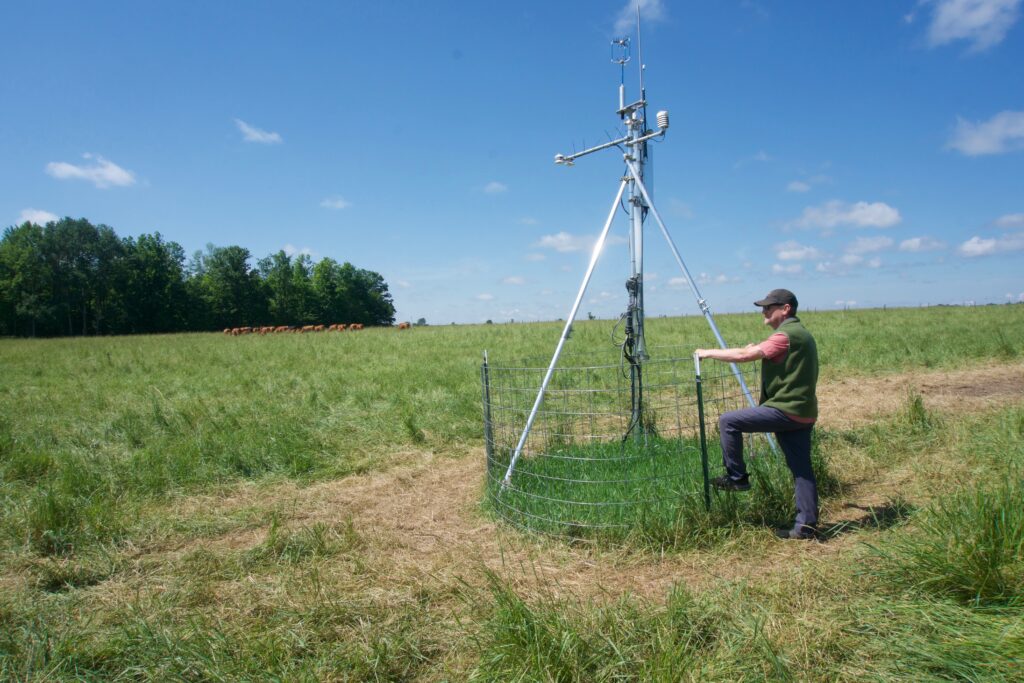

Rowntree installed all manner of monitoring and sampling devices to measure changes in ecological performance over time. The instruments monitor organic matter in soil, water quality, grass growth, and the health and development of the animals. He documents costs and measures the efficiency of rotational grazing, arguing that the technique improves farm profitability.

As causes and solutions to climate change have climbed to the top of public priorities in recent years, Rowntree has also set out to prove that rotational grazing enhances carbon storage in growing plants and in soil. As part of the new project, Rowntree turned to earth science sensing instruments and drones linked to orbiting satellites. The equipment measures wind speeds, concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide, water vapor, temperature, and pressure in order to calculate the amount of carbon dioxide and water moving from the atmosphere into the soil and from the soil into the atmosphere.

The data is meant to test Rowntree’s thesis that grazing cattle in rotational systems stores more carbon than it releases, improves water quality and supply, and can be part of the solution to our warming Earth.

atmospheric carbon dioxide, water vapor, temperature, and pressure. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

Across the U.S.

A crucial piece of the five-year project is its national scope. Rowntree has recruited university researchers and 60 additional rotational cattle operations in Michigan and four other states — Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, Wyoming — to document similar measures of ecological and economic performance. In essence, Rowntree has developed the most intensive research project in the country to understand how livestock management affects ecological function.

The findings not only apply to the 10,000 farms raising Michigan’s 238,000 beef cattle in a $650 million annual industry. They also are relevant to the 30 million beef cows and calves raised on U.S. farms and ranches, and the 655 million acres [BW1] of rangeland and pasture across the country.

“Dr. Rowntree’s research addresses critical challenges and opportunities in the beef production industry, aiming to create a more sustainable, resilient, and profitable future for beef producers,” wrote Isabella De Faria Maciel, systems researcher at Oklahoma-based Noble Research Institute and co-leader of the project, in an email message.

Noble Research, The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research, Greenacres Foundation, Jones Family Foundation and ButcherBox funded the project. De Faria Maciel added: “His project explores ways to make beef production more resilient to climate change. This involves developing strategies for managing cattle and pastures in the face of extreme weather events and shifting climate patterns.”

In a project devoted to metrics and measurements, the true test will be whether proven techniques are adopted. Other land grant university researchers have also developed crop and livestock practices that lower costs and are less environmentally damaging. Most have been rejected by mainstream agriculture, which is the largest water polluter in U.S. history. Moreover, when it comes to environmental protection, agriculture is so politically influential that state and federal governments ask little more from livestock and crop farmers other than that they voluntarily curb the amount of fertilizer, pesticides, and manure that flow into state and national waters.

Rowntree thinks the study results will provide a compelling case: “If we can indeed show this carbon being absorbed and stored in the soil over a greater period of time, we offset a tremendous amount not only of the greenhouse gases going up in the atmosphere. We strengthen resilience of that system. Those systems that are getting enhanced have higher functioning water cycles. They’re more productive and farmers can be more profitable. So that’s the drivers behind it. It’s improving wellbeing in rural communities through management of ecosystems.”

Big Challenge

Cattle production is particularly damaging to land, water and climate. Big conventional cattle feedlots are major sources of pollution almost everywhere they are located, according to state environment departments. The World Resources Institute, a respected Washington-based environmental think tank, found that cattle, dairy cows, and other livestock are responsible for over 30 percent of global methane emissions — a greenhouse gas that has global warming potential 80 times higher than that of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

Rotational grazing, while attracting increasing numbers of American ranchers and farmers, is not close to becoming mainstream in U.S. cattle production.

Rowntree is not discouraged. “I like our goals,” he said. “I see huge, huge opportunities to enhance education to increase management of these systems that give us the triple bottom line responses we want — environmental, profitability, and socially improving our communities. Our goal is to understand how much carbon is possible in these systems. How much carbon can we actually build? We have 600 million acres to work with. It’s a huge terrestrial storage of carbon.”