Like divers surfacing above a sea of noise and ambivalence, negotiators in Paris on Saturday reached an agreement that commits nations to develop new energy strategies that hold “the increase in the average global temperature to well below 2 degrees C” and to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C.”

The Paris accord is momentous for innumerable reasons, not the least of which is because it recognizes, at last, that three powerful and unyielding economic and ecological trends have merged to relentlessly push governments to act. All are prompted by the collision between the resource-abundant development approach of the 20th century, and the increasingly dire environmental conditions of the 21st.

Since 2008, as a correspondent reporting on the global confrontation between rising demand for energy and food in the era of diminishing freshwater reserves, I’ve been a frontline eyewitness on five continents to our rapidly evolving circumstances.

By far, the most important change in our circumstances is that Mother Earth is fuming. The planet is pushing back hard, very hard, against mankind’s industrial depradations. Hurricanes drowned two American cities.  Mammoth wildfires race across the West, burning hottest in the fuel-stoked forests where fire was deliberately suppressed. Toxic algae contaminates drinking water drawn from warmer and more polluted rivers and lakes all over the world.

A Rein of Global Disorder

An earthquake this year damaged 14 hydropower dams in Nepal. In June 2013, a vicious flood that scientists linked to climate change killed thousands of people in Uttarakhand, India and wrecked that Himalayan state’s hydropower sector. A tsunami in the Pacific Ocean in 2011 killed 16,000 people and shut down Japan’s seawater-cooled nuclear sector.

Deep droughts have been especially dangerous. Brazil’s largest city, America’s largest state, and nearly all of South Africa contend now with serious water scarcity. A 12-year dry spell in Australia’s food-producing Murray-Darling basin ended in 2010, but not before it caused the largest rice industry in the southern hemisphere to collapse. More than 1 million metric tons of rice vanished from world markets. Australia’s wheat growers, typically the world’s sixth largest exporters, managed to harvest just over half of the 20 million metric tons of grain they normally produced. Both harvest failures contributed to rising grain prices. Recall that the Arab Spring in 2010 was touched off by rising food prices.

This year, a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States added fresh, peer-reviewed details about how a malicious four-year (2007 to 2010) drought in Syria played a role in igniting the calamitous civil war in 2011. The long rein of water scarcity ruined the farm economy, and drove over 1 million farmers and their families into unstable resource-scarce cities inspired by the Arab Spring to rebel against authoritarian rule.

The second piece of the global transition is the development of influential civic campaigns to push for climate action, and against big infrastructure projects, especially in the energy and mining sectors around the world. In the U.S., in response to powerful citizen protest, President Obama in November rejected the Keystone XL oil pipeline from Canada. In India, farmers and activists, afraid of flooding and loss of farmland, blockaded access roads and brought construction of the 2,000-megawatt Lower Subansiri Dam to a halt in 2010. In Peru, villagers in the Andes highlands near Cajamarca halted development of Newmont Mining’s $5 billion Conga gold and copper mine because of local concerns about water pollution. In Mongolia, a grassroots campaign by desert livestock herders who are linked online to international advocacy organizations and foundations, forced Rio Tinto to design and build a state-of-the-art gold and copper mine that recycles water and limits pollution with a closed loop manufacturing process.

Trouble in Finance Markets

The third and newest piece of the narrative is the apprehension about approving big energy development loans that is accumulating in global finance markets, especially those intent on funding carbon-based projects, and to a lesser extent hydropower development.

Summed up by “leave it in the ground†messages affixed to posters waved this month at the Paris Climate Conference, the attention that big energy projects are attracting in the finance world owes its influence to three reports:

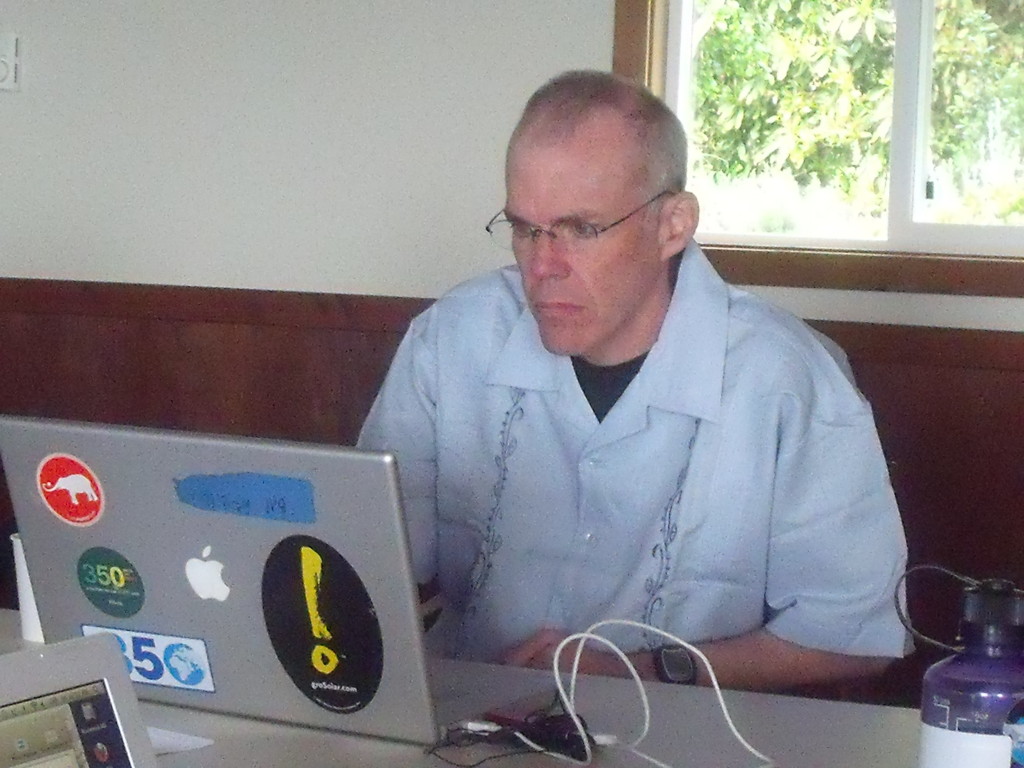

In 2009 researchers at the Pottsdam Institute, a German research group, determined that keeping the rise in global temperatures within the 2 degrees Celsius survivability limit that has been embraced by most nations meant that no more than 565 more gigatons of carbon dioxide could be poured into the atmosphere.  In 2011, the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a British research group, found that 2,795 gigatons of carbon is held in the coal, oil and natural gas reserves of fossil fuel companies, and carbon-rich countries. In 2012, author and climate activist Bill McKibben explained “global warming’s terrifying new math†in an article in Rolling Stone. In order to prevent what scientists project could be disastrous planetary heating, 80 percent of known fossil fuel reserves cannot be developed.

Big banks and other finance institutions have spent the three years since coming to terms with the market risks of stranding fossil fuel assets valued at more than $US 20 trillion. A disinvestment campaign led by McKibben has recruited over 500 institutions, with assets valued at over $ 3.4 trillion, that have pledged to remove their funds from fossil fuel companies and projects.

For the time being, the global coal sector is most imperiled. Natural gas and renewable energy sources are replacing coal-fired plants in the U.S. and Europe. American coal production and exports are declining, along with international prices for coal. Europe’s largest insurer, Allianz SE, recently joined California’s pension funds and Norway’s sovereign wealth fund to sell its coal investments.

In August, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, that nation’s largest bank, announced it would not fund the proposed Carmichael mine in Queensland, the biggest coal mine ever proposed in Australia. The mine’s role in adding to carbon emissions, potential damage to the Great Barrier Reef from coal transport ships, and a vigorous opposition campaign led by Greenpeace were factors in the bank’s decision.

Last month, the United States and other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which represents the world’s richest countries, agreed to eliminate export subsidies for the least efficient coal plants. It’s a measure that takes effect in 2017.

Also in November, the Financial Stability Board, which oversees global financial regulation for the Group of 20 (G20) economies, announced it was establishing a task force, chaired by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to encourage businesses to voluntarily disclose how much risk they face from adjusting practices due to climate change.

And New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman last month concluded a long securities investigation and won an agreement to require Peabody Coal, the largest publicly traded coal company in the world, to more honestly and accurately disclose to investors the risks the company faces from new regulations and coal market turbulence as a result of climate change. Peabody’s stock value, which four years ago reached nearly $US 1,100 a share, is now trading at under $US 10 a share.

The indifference that for too long distinguished global attitudes about the Earth’s safety is giving way to needed measures of responsibility. Still, there’s one vital place on the planet where the sediments of illusion remain undisturbed: the U.S Congress.

The tissue of Republican dogma about climate change and climate science will eventually rupture. The California drought, the Australian drought, the Uttarakhand flood, the Sao Paolo drought, Syria’s civil war, and so many other recent ecological and economic disasters formally linked to climate change, are pouring the waters of inescapable reality into the party’s dark grotto of denial.

A version of this article appeared in the December 16, 2015 editions of the New York Times and the International New York Times.

— Keith Schneider