NEW YORK — In the evenings the sidewalks along First Avenue, between 10th and Houston Streets, are a jammed bustle of young people crowded into bars, lined up for tables at good restaurants, or walking fast with heads bowed and faces lit by incoming smart phone texts.

First Avenue, like so many other neighborhoods in New York, is a tableau of urban revival, an example of what happens when smart investments and informed entrepreneurism foster economic and environmental transition. New York City, you may recall, was in such dire shape in the 1970s and 1980s that crime ruled the streets, fiscal collapse was ever-present, and people and companies left in droves. First Avenue in those days was dirty, dark, and dangerous.

New York is not that place anymore, and hasn’t been since the start of the century. New York is an engine of growth and job opportunities, a city with clean air, ample and safe parks, improving water quality, slim people, improving schools, and an attitude of confidence and hope. In all of these attributes New York also resembles Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Louisville, Pittsburgh, Washington, Denver, Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, Boise, Dallas, Charleston, Cincinnati and most other major American metropolitan regions.

In each of these cities job growth is climbing rapidly, crime is stable or declining, unemployment rates are lower than the state at large, and real estate values are heading up, in many instances swiftly. In other measures American cities are a study in improving social conditions and prosperity. Wages are rising. Young adults attend college and are getting married. And, just as First Avenue’s businesses and watering holes are busy with customers, so too are the mercantile streets of big cities across the country.

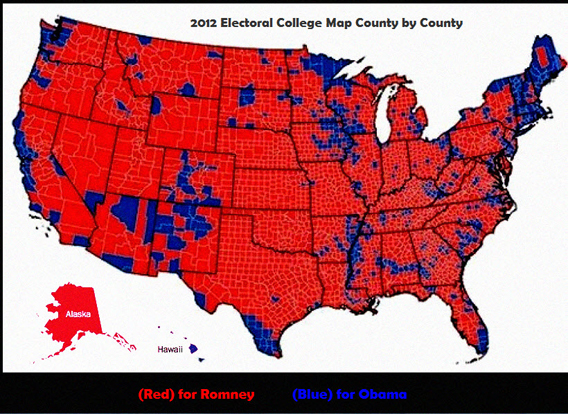

Oh! There’s one more distinction. American cities are overwhelmingly filled with adults who support Democrats for state and national offices. They are also filled with adults who not only generally believe that the rest of America is getting along better like they are, they have just the scantest idea of the depth of the dismay, the anger, the resentment that people in the far suburbs and rural regions have for cities and their residents.

Those divisions now express themselves in dangerous ideas harbored in the Republican party about limiting state and federal investments in transit, education, streets, law enforcement, housing, business loans, and environmental safeguards. But even as they support a risky agenda of tax-cutting and smaller government, many of those very same voters and their families have also chosen you’re-on-your-own results — limited job opportunities, low wages, and hardship.

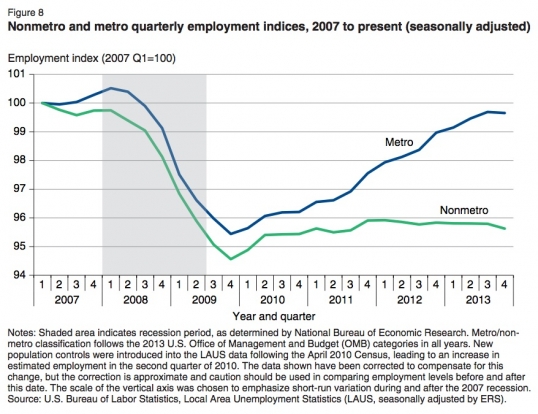

The gap between urban wages and rural wages is widening. So is the gap between job growth in cities and job growth in rural and suburban areas. Crime is mounting in outer suburbs and rural areas, principally driven by the outcomes of despair — unemployment and drug addiction.

Over the last decade and a half 25 million American jobs were lost. Cities have recovered and are adding new jobs. Outside cities, job growth has not recovered and some 5 million jobs are missing. In thousands of counties a $10-an-hour job without benefits is all that’s available.

Cities succeeded because they had to go it largely alone in raising funds to modernize or build big public projects — parks and waterfronts, transportation, housing, schools and the like. But they also need federal support and are having a hard time receiving it.

Here in New York, for instance, the rail tunnels carrying hundreds of commuter and interstate trains under the Hudson and East Rivers are over a century old and in need of expansion in an era of rising traffic congestion, climate change, and higher energy costs.

Federal grants were made available in the early part of the century to add two new rail tunnels at a cost of $10 billion or so. Four years ago, though, New Jersey’s Republican Governor Chris Christie killed the grants largely to prove his cost-cutting bona fides to the austerity-infatuated far right.

It was a move that Christie believed would firm up his 2016 presidential candidacy. But causing those funds to vanish also is injuring the economy of his state, New York City, and could affect the Washington to Boston passenger rail corridor, the busiest in the United States.

Two years ago Hurricane Sandy drowned New York, filled the existing rail tunnels with brackish water, and caused deterioration in brick and concrete work that is over a century old. In August, in what is likely to be a painful and persistent indication of long delays to come, a piece of concrete in one of the tunnels broke free from the roof, shattered on the tracks, and slowed rail service to a crawl for more than a day.

Hundreds of thousands of people in and outside New York depend on trains for work. So do millions of Americans in other major metro areas. Passenger counts on rail systems are steadily rising.

But tens of millions of Americans in outer suburbs and rural areas could care less. Trains are a piece of public transport infrastructure deemed by voters outside metro areas to be so expensive, elitist, and unnecessary they ought not to receive any federal and state funding at all. That’s why the Republican governors of Ohio, Wisconsin, and Florida turned back billions of federal stimulus funds in 2009 that were intended to develop faster rail service in the Midwest and South.

Very clearly, if limited rail service hurts the economies of the cities of the Northeast, it hurts the economy of the nation. If giant climate-disrupting hurricanes drown the nation’s financial capital, it raises costs for the nation. If urban roads aren’t repaired and schools crumble it hurts the competitiveness of the nation.

America’s city residents care about those investments and generally support lawmakers that approve of making public investments for public purposes. Cities are making those investments and have emerged this century as the most important engines of economic performance in the United States.

They also have become prosperous, multi-cultural, and technologically competitive islands surrounded by a seething sea of conservative social and economic distress, and the radical dogma those conditions inspire.

In places far from the tall buildings too many voters see in public investment a waste of money, a violation of their principles, an attack on the values of hard work and independence. That is, of course, unless it’s their public money. The farm price support subsidies, after all, cost taxpayers $168 billion over the last decade.

A juvenile politic has gained priority that covets guns, believes the Earth was created 10,000 years ago, is suspicious of people of color, discounts sound scientific research, believes in “traditional family values” — whatever they are — fears the future, and doesn’t think much of the contributions of cities and their residents.

Unfortunately for America, that view prevails. Tax-cutting, austerity-loving conservatives are expected to do well in next month’s national and state elections. New York’s crumbling rail tunnels will have to wait to be rebuilt.

— Keith Schneider

The Democratic problem is that it doesn’t believe that the juvenile gains you speak of have been something that they themselves have allowed to happen as much as the republicans have made happen. People aren’t born coveting guns or believing the earth was created 10,000 years ago. They have been taught that.

From a friend who served in state government in the South:

Actually, about ten years ago, the House Republican Study Committee did a map that compared population density with partisan preferences. Even in bright blue California, the relationship was very strong, and so they opted for a very sophisticated strategy based less on “rural†and more on density. Large lot developments in urbanized areas tend to be very affluent Republicans. Further out, single family suburban developments are more likely to be republican than a town house development down the road—and election districts are carved to capture those “pockets of opportunity.†This analysis has even colored their chose social and hot button issues—they understood that people who live close together have to be tolerant……of religions, foods, noise, smells, appearances, etc. They are perfectly happy preaching a gospel of intolerance, not so much because they believe it, but because it wins with “their†voters.

Your article is great, and the history is even darker. This is not a play on dark, primal emotions. It is a function of deliberate research.

So, density and tolerance are bad. What’s good? “Liberty,†me in my own goddamn auto, me and my own goddamn gun, me in my house where I never see or hear a neighbor, etc. etc.

“In places far from the tall buildings too many voters see in public investment a waste of money, a violation of their principles, an attack on the values of hard work and independence.” Of course, some of the largest public investments have been made in the suburbs. They would not exist but for huge federal investments in highways, water & sewer systems, etc.

Of course, when infrastructure works well, it becomes invisible. We don’t notice the road until we hit a pot hole. We don’t notice the traffic signals until we get stuck at an intersection where the signal timing is off. We don’t notice electricity until the power goes out. Also, when the suburbs were new, their massive infrastructure systems required little funding for maintenance or rehabilitation. So new suburban residents enjoyed pristine infrastructure and low taxes.

During the same period after WWII as the suburbs were being manufactured, government finance moved away from user fees toward more general revenue sources like income and sales taxes. Thus, people lost a sense of connection between the taxes that they were paying and the governmental resources that they were receiving. Imagine the difference between paying a per-gallon fee for water (as most of us do) and paying for water via a sales tax.

Today, suburban infrastructure is beginning to crumble. The federal largesse that built it is not available to maintain and replace it. Suburbanites sense that they are paying significant taxes, but don’t feel that they know how their money is being spent. And due to deterioration of their infrastructure, they feel that it isn’t being spent on them.

Part of the solution to the political disconnect is to replace general taxes with user fees and access fees (“value capture”) that can help reconnect people to the services that they receive in exchange for the taxes that they pay.

For more info, see “Funding Infrastructure for Growth, Sustainability and Equity” at http://media.wix.com/ugd/ddda66_d46304b5437c178e2f092319a6f30364.pdf

The elitist, the world-revolves-around-us attitudes displayed in this article are precisely why people in the suburbs and rural areas dislike city residents. If you’re doing so well, raise your own darn funds to build tunnels.