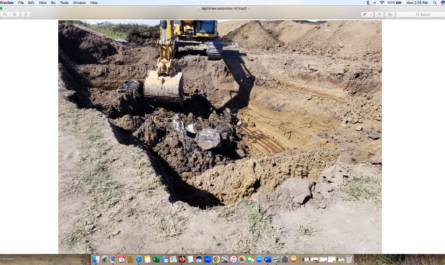

and animal agriculture is over half the problem. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

LANSING. Mich. – Because lawmakers and regulators embrace the principle that agriculture’s primary objective is to feed people, farming is a sacrosanct industrial sector in the United States.

Understand that every industry in the U.S. except for agriculture is required to limit water pollution. But ever since 1972, when Congress exempted farming from most of the water-cleansing requirements of the Clean Water Act, farms have been perfectly free to discharge into the environment some of the most dangerous chemical compounds known to man. Billions of pounds of toxic pesticides were sprayed on crops and orchards. Hundreds of millions of tons of bacteria-fouled and nutrient-saturated manure were spread on fields and pastures.

The primary defense offered by government and allies in America’s agricultural universities: farmers can voluntarily take steps to cultivate cover crops and plant grassy absorbent buffer strips along ditches and streams. It is guidance that most farmers disregard. The terrible consequence is that farm chemicals are fouling drinking water wells and streams in every important farm state. Nitrates from chemical fertilizer and manure are now the nation’s most widespread water pollutant, and one of its most hazardous.

Agriculture, in short, is the source of the worst and most dangerous water contamination in U.S. history.

Michigan Takes Action

That’s why what happened in Michigan late in 2025 is so encouraging to those of us convinced that agriculture doesn’t have to be as reckless with its discharges as it has been. On October 29, Phillip Roos, director of the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, known as EGLE, issued new requirements to the state’s big livestock and poultry producers to more safely manage the brown tide of manure they spread each year on farm fields.

Several of the new measures include actual prohibitions – almost unheard of in agriculture – to halt practices that cause contamination.

For instance, Michigan now bars producers from spreading manure on fields from January 1 to March 19. Pouring cattle and hog poop on ice and snow is a slippery slope for contamination to slide straight into drainage ditches and from there to streams and rivers.

Michigan now bans producers from hauling manure in winter from their dairies and hog facilities to fields owned by other landowners. This common practice, known as “manifesting,” would have been the central strategy enabling farmers to evade the winter-spreading prohibition.

Michigan requires large facilities that confine and feed thousands of animals to have six months of storage capacity for manure. But the state has new authority to require producers to install groundwater monitoring capacity to ensure they aren’t leaking into state aquifers.

Reducing Pollution in Already-Polluted Watersheds

A fourth group of new restrictions focuses on not allowing dairy, hog, and poultry producers to worsen the condition of already-polluted Michigan streams. There are more than 130 so-called “impaired” waterways in Michigan. A number of them flow in watersheds in which large confined animal feeding facilities contribute to pollution. Fourteen are impaired specifically by farm nutrient contamination. Nearly 26,000 miles of rivers are impaired by E.coli, the dangerous intestinal bacteria associated with human and animal wastes.

With the exception of requiring dairy cattle to be fenced off from streams none of the impaired watersheds where farming is the primary source of pollutants have yet been successful in reaching targeted levels for reducing pollution.

Director Roos set out to change that circumstance. EGLE’s recent rules give state regulators new authority to issue operating permits individually tailored to reduce manure contamination from the state’s 290 large livestock facilities. The intent, Roos said in his order, is to ensure water quality standards. The new measures include requiring producers to sample soil in fields and not spread where the ground is already too saturated to absorb more animal waste.

Court Action

All of these changes in policy and practice are the result of five years of litigation between the state, the farm industry represented by the politically powerful Michigan Farm Bureau, and an alliance of nonprofit environmental law groups, among them the Environmental Law and Policy Center of Chicago and Flow Water Advocates in Traverse City.

The Farm Bureau, a foe of regulation, challenged EGLE’s attempt in 2020 to tighten and lessen manure spreading practices. Attorney General Dana Nessel, assisted by the non-profit groups above, defended the state environmental agency’s authority to protect state waters. In the summer of 2024, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in the state’s favor, issuing what is arguably its most important environmental decision this century.

By a 5-2 margin, the Court said environmental regulators have full authority to require big livestock and poultry operations to improve their slipshod manure management practices that cause serious contamination of state waters.

In 2024, EGLE also made one more critical decision to limit pollution from manure. It determined that the new generation of manure digesters being developed across Michigan are industrial facilities. Digesters cook manure to produce marketable supplies of methane for use as fuel in vehicles and power plants. Michigan ruled that the byproduct wastes, known as “digestate,” would be regulated in the same way discharges are regulated if they came from a factory. The decision is a sharp departure from other farm states, which regard digesters as ordinary farm equipment and are thus exempt from oversight. In most states, digestate – which is more toxic than ordinary manure – is allowed to be spread in fields without restrictions.

Phil Roos deserves a lot of credit for the decisions he made in October. They are the third clear and decisive step Michigan has taken to curb the industry responsible for so much of the state and nation’s water pollution. No surprise. On December 18 the Michigan Farm Bureau and operators of 163 large livestock operations filed a case in state circuit court to prevent Roos’s rules from going into effect. The operators threatened to leave the state if they did. With all the land, equipment, money and expertise they already invested in their operations, those threats appear hollow.

In issuing such determined measures to tackle the rising tide of manure pollution, Phil Roos joins Dana Nessel, the state Supreme Court, nonprofit groups, and the staff of the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy in pushing Michigan to the forefront of the exceedingly difficult work of reducing the terrible contamination of America’s waters from agriculture.

— Keith Schneider