I met Stewart Udall, and his wife Lee, in 1988 when I was a national correspondent for the New York Times and he was in the midst of seeking compensation for American victims of the nuclear weapons industry. It was the start of a friendship of 22 years that ended today with Stewart’s death.

Stewart, who was 68 at the time, and Lee were getting ready to move into a beautiful adobe-style house they were building in the hills above Santa Fe. He managed a law practice that represented Navajo uranium miners injured by radiation exposure, as well as the families of miners who’d died. They both were active in promotion of the arts, a facet of the expansive Udall interests that the couple brought to the Kennedy administration in the early 1960s.

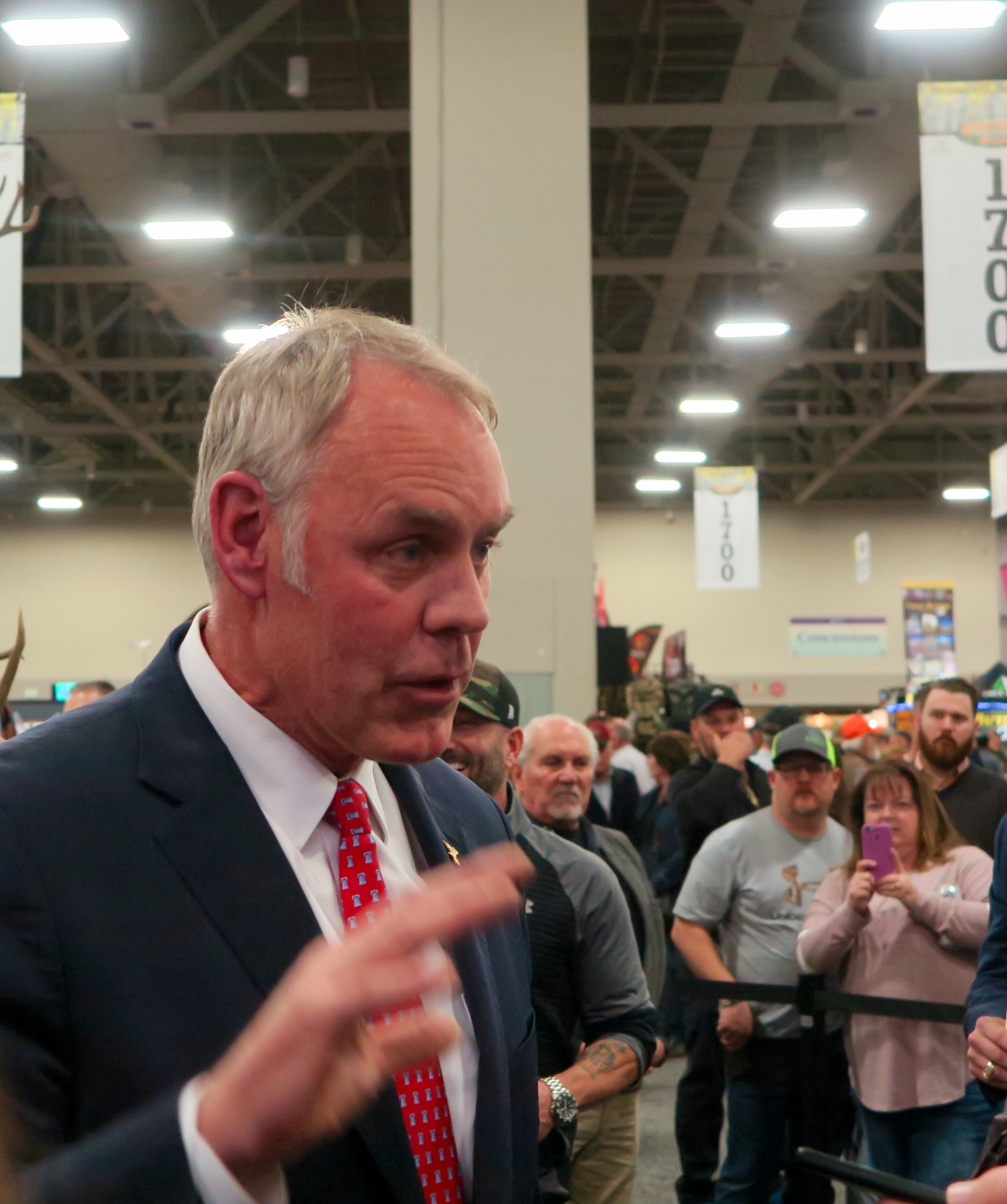

I wrote several articles about Stewart in the Times and we got to know each other well. He invited me to get to know his children – Tom, now a United States Senator, Lynn, Lori, Denis, Scott, and Jay. And in June 1998, three years after I left the Times to launch the Michigan Land Use Institute, Stewart responded to my invitation to speak in northwest Michigan by spending the weekend and appearing at a fund raiser for the Institute, and at an emotional standing room only public gathering at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. He was the first Secretary of the Interior to ever visit the park, which he helped to establish. It was one of the most memorable weekends of my life. The picture above was taken that day by J. Carl Ganter.

President Obama honored Stewart today with this statement from the White House. “For the better part of three decades, Stewart Udall served this nation honorably. Whether in the skies above Italy in World War II, in Congress or as Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall left an indelible mark on this nation and inspired countless Americans who will continue his fight for clean air, clean water and to maintain our many natural treasures. Michelle and I extend our condolences to the entire Udall family who continue his legacy of public service to this day.”

Stewart Udall made his life count for principles, especially the respect he and his family shared for the land, the arts, and justice that are now embedded in the nation’s culture and economy and way of life. It’s not much of a leap to note that the work he executed during his life, like the wild ground he preserved in national parks and refuges, will endure for as long as this nation endures.

In our many conversations, especially those over the last year, I often suggested how lucky he was to serve when he did. It was a golden age of policy making and Stewart was right at the center of it.

I still write for a number of desks at the Times and prepared the first draft of Stewart’s obituary. The edited piece that appeared in the paper on Sunday, March 21, 2010 was based on this draft, which appears here in its entirety.

—————————————————————

Stewart L. Udall, who as Secretary of Interior in the 1960s helped to invent innovative new safeguards for the nation’s natural treasures and added vast holdings to the public domain with statesmanship and flair rivaled only by President Theodore Roosevelt, died today of natural causes. Mr. Udall, who celebrated his 90th birthday on January 31, was surrounded at his death by his six children.

Mr. Udall was 40 years old and a three-term Democratic congressman from Arizona when President John F. Kennedy asked him to become the first person from that state ever to serve in the cabinet. A resolute liberal from the conservative West, he was the last surviving member of Mr. Kennedy’s original cabinet.

In the more than eight years that he led the Interior Department, a tenure that also spanned the entire administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, Mr. Udall was the federal government’s most tenacious advocate for environmental conservation. He forged strong personal ties with the small group of lawmakers, attorneys, conservation leaders, and writers then working in Washington who helped lay the foundation for a generation of landmark statutes to secure the nation’s air, water, and land.

Few corners of the nation were left untouched by Mr. Udall’s principled approach and his ability to work collaboratively with Congress. He added 3.85 million acres to the public domain, including four national parks – Canyonlands in Utah, Redwood in California, North Cascades in Washington state, and Guadulupe Mountains in Texas – six national monuments, eight national seashores and lakeshores, nine national recreation areas, 20 historic sites, and 56 wildlife refuges.

Mr. Udall also was the government’s primary advocate for the 1964 Wilderness Act, which permanently ensured that millions of acres of wild land would remain “untrammeled by man.” He was the intellectual force behind the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which directed fees and royalties from offshore oil and gas drilling to pay for wilderness protection and recreation. Mr. Udall also campaigned to preserve America’s historical heritage, and played a big role in saving New York’s Carnegie Hall from the wrecking ball. Among his rare missteps, which Mr. Udall readily acknowledged, was approving federal oil and gas leases off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, which led to a devastating 1969 oil spill.

Following President Kennedy’s assassination, Lady Bird Johnson urged her husband to retain Mr. Udall. The two had become close and worked together on a program to plant flowers and beautify Washington, D.C. Near the end of the decade he helped to write and actively promoted the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which protected some of the nation’s most beautiful rivers.

Although Mr Udall cultivated congressional allies, his most important friend on Capitol Hill was his younger brother, Representative Morris Udall, who succeeded him as an Arizona Congressman, rose to become chairman of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, and in 1976 ran for president in a campaign that his older brother managed. Most of the significant environmental and land protection statutes that became law in the 1970s and 1980s, including the Endangered Species Act, bore their stamp and influence.

“That was a wonderful time and it carried through into the Nixon administration, into the Ford administration, into the Carter administration,” Mr. Udall said. “It lasted for 20 years. I don’t remember a big fight between the Republicans and Democrats in the Nixon administration or President Gerald Ford and so on. There was a consensus that the country needed more conservation projects of the kind that we were proposing.”

President Kennedy’s murder in 1963, followed by Robert Kennedy’s assassination in 1968, were personal blows that marred his optimism. In many ways, though, Mr. Udall represented the most enduring legacy of the Kennedy administration’s promise and its attitude.

He engaged his work with a sense of adventure, dynamism, and sheer delight that reflected the administration’s youth and idealism. It was Mr. Udall who made the suggestion, embraced by President Kennedy, to invite Robert Frost to recite a poem at the young president’s inauguration. Mr. Udall accompanied Mr. Frost to the Soviet Union in 1962, a trip meant to foster better ties with Premier Nikita Kruschev. He held evenings at the Interior Department with poet Carl Sandburg and actor Hal Holbrook.

A man who prided himself on his fitness – he was an all conference guard on the University of Arizona basketball team – Mr. Udall climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro in Africa, and Mt. Fuji in Japan while heading U.S. delegations to both regions. When he was 84-years-old, at the end of his last rafting trip on the Colorado River, Mr. Udall hiked up the steep Bright Angel Trail from the bottom of the Grand Canyon to the south rim, a 10-hour walk that he celebrated at the end with a martini.

Mr. Udall, and his wife, Lee, were especially friendly with Jacqueline Kennedy, and were close to Robert and Ethel Kennedy, whose children were about the same age as Mr. Udall’s six children. Mrs. Udall, who died in 2001, once pushed the historian, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., into the pool fully clothed during a rambunctious party at Robert Kennedy’s Hickory Hill estate in Virginia, a moment that delighted her husband for years afterward.

But it was Mr. Udall’s sense of fairness, his allegiance to the land, and his admiration for those that spoke out in its defense that most distinguished his life and work. He invited Pulitzer Prize-winning author Wallace Stegner to be the department’s writer in residence. Mr. Stegner’s presence prompted Mr. Udall to write The Quiet Crisis, his best selling 1963 book on the new environmental ethic taking shape in the nation. Their friendship ended tragically in 1993 when Mr. Stegner was killed in an auto accident in Santa Fe, New Mexico while visiting Mr. Udall at his home.

In 1962, when Rachel Carson’s critical analysis of the risks of pesticides, Silent Spring, was denounced as specious by the chemical industry, Mr. Udall publicly defended Ms. Carson’s scholarship, personally introduced her to President Kennedy, and convinced Mr. Kennedy to appoint a presidential science advisory committee, which a year later confirmed her findings. In April 1964, Mr. Udall served as a pallbearer at Ms. Carson’s funeral at the Washington National Cathedral.

Mr. Udall applied the same doggedness and loyalty to his important work in the late 1970s and through the 1980s as a lawyer representing thousands of uranium miners, nuclear weapons industry workers, and citizens exposed to radiation from atomic weapons manufacturing and testing in the West. Operating on a scant budget, and with the assistance of his wife, three of his children, and a small team of lawyers, Mr. Udall filed class action lawsuits that pried open the government’s secret Cold War legacy of scientific deceit and mismanagement within the multi-state American nuclear weapons industry.

Though he won the first case in 1984 in federal district court, an appeals court overturned the ruling and the U.S. Supreme Court declined in 1988 to hear arguments. Mr. Udall then turned to Congress, working with lawmakers of both parties, particularly Republican Utah Senator Orrin Hatch and Democratic Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy. In 1990 President George H.W. Bush signed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. The law, administered by the Department of Justice, provided up to $100,000 for those sickened by radiation exposure, and issued a formal apology for the “harm” done to American citizens who were “subjected to increased risk of injury and disease to serve the national security interests of the United States.” In 1994, Mr. Udall published the sixth of his eight books, The Myths of August: A Personal Exploration of Our Tragic Cold War Affair With The Atom, a highly regarded account of the weapons program and the struggle for justice.

Stewart Lee Udall was born on January 31, 1920 in St Johns, Arizona during an era when the tiny settlement still bore much of its remote, tough, old West character. His grandfather, David K. Udall, helped to settle St. Johns, arriving there in 1880, seven years after its founding as a way station for wagoneers hauling U.S. Cavalry supplies from Santa Fe to Fort Apache. His father, Levi S. Udall, was a justice on the Arizona Supreme Court. His mother, Louise Lee Udall, was active in civic affairs and a gifted writer who instilled in her son the love for ideas and the words to express them.

Mr. Udall’s great grandfather was John D. Lee, who was convicted and executed in 1877, 20 years after 120 California-bound emigrants from Arkansas were slaughtered by Mormon zealots in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. In 1989, at the urging of descendants of the Arkansas victims, Mr. Udall agreed to bring about reconciliation, helping to organize a memorial event in 1990 and erect a monument to what he called the greatest tragedy in the history of the West.

Mr. Udall served as a gunner for the U.S. Army Air Force during World War Two. In 1948 he graduated from the University of Arizona with a law degree and went into private practice for two years, then formed Udall & Udall, a joint practice with his brother. In 1954, Mr. Udall was elected to Congress.

He is survived by his son Tom Udall, a Democratic Senator from New Mexico and his other children, Lynn, Denis, Scott, Lori, and James. He also is survived by a nephew, Democratic Senator Mark Udall of Colorado, and eight grandchildren.

One of Mr. Udall’s last essays was his “Letter to My Grandchildren,” which the Michigan Land Use Institute originally published in 2005, and has done so every December since on its Web site. It reflects his penetrating insight about grievous risks to the economy and environment from global climate change, and his judgment about the capacity of his heirs to respond. “Operating on the assumption that energy would be both cheap and superabundant, I admit, led my generation to make misjudgments that have come back and now haunt and perplex your generation,” he wrote. “We designed cities, buildings, and a national system of transportation that were inefficient and extravagant. Now, the paramount task of your generation will be to correct those mistakes with an efficient infrastructure that respects the limitations of our environment to keep up with damages we are causing.”

Keith, thank you for this moving and enlightening remembrance.