chemical waste at the Sievers Family Farm in Iowa. (Photo/Iowa DNR)

The Iowa Capitol Dispatch, one of the fine non-profit online news organizations at the center of the country, posted an article last week by Jared Strong that caught my attention. Following more than a year of administrative pondering the Iowa Department of Natural Resources on November 30 fined a prominent cattle farm in Stockton $5,000 for illegally burying barrels of chemical waste on its land.

Why, you ask, would such a modest fine issued by a Corn Belt natural resources department generate even the slightest ripple of interest? A couple of reasons. First as a career-long environmental journalist who came of age reporting on Love Canal and the discovery of toxic dumps across the country, I’m sensitive to any discovery of buried barrels of waste.

Second, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, according to a number of former and current staff members I talked to this year, has basically abandoned its responsibility to regulate air emissions and water discharges from agriculture. This year, for instance, the DNR had the opportunity to protect groundwater by requiring better construction and oversight of manure storage lagoons at large livestock operations. The agency dropped the effort in November. There’s a reason that commercial fertilizer and livestock waste have produced widespread surface and groundwater contamination in Iowa.

Third, I know the recipient of the fine — Bryan Sievers, a former Republican state representative who owns and manages Sievers Family Farms in Scott County west of Davenport. I interviewed him last spring for an article in The New York Times.

The Sievers operation is well-known In Iowa and other states for its innovations in manure biodigestion. Sievers’ biodigesters slowly cook liquid feces and urine from 2,400 cattle in an oxygen-deprived (anaerobic) bacterial broth to produce methane. Sievers uses the gas to fuel generators that produce electricity for the cattle feeding operation and the Iowa grid.

In November, Sievers was among the most prominent participants at a conference on manure biodigestion at Iowa State University that was sponsored by Chevron and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. His farm is a partner with Roeslein Alternative Energy, which developed efficient manure biodigesters on huge hog farms in Missouri and several more states and is one of the country’s largest producers of so-called “renewable natural gas.” Federal authorities think so highly of Roeslein that the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded the company an $80 million ‘Climate Smart’ grant last year to oversee a multi-state project to prove what the government believes is the virtue of manure biodigestion to the climate, land, and water. Sievers’ cattle operation is one of the installations involved in the project.

In our NY Times interview Sievers told me how satisfied he is with generating fuel from manure. “I like the model of a closed loop system,” he said. “Let’s just start with the corn that feeds the cattle. The cattle feed us and the digesters. The digester feeds methane to the electric grid. We spread the remainder, the digestate on our soils to feed the crops, which then turns around and feeds the cattle again. I just love that story. That’s basically what we’ve been pursuing and implementing.”

I wasn’t aware, when I interviewed Sievers, of the farm’s clouded operating record. In June 2021, a 54-year old contract scuba diver was killed in one of the farm’s biodigesters. Due to the regulatory coddling that agriculture has won from states and the federal government, Sievers’ digesters are exempt from workplace safety oversight. No investigation occurred to understand what happened.

Almost exactly a year later, in late June 2022, an anonymous source reported to E.P.A. that as many as 100 barrels of waste were illegally buried at Sievers Farms. According to records made public by the Iowa DNR, and in an interview with Jake Forgie, the state DNR environmental specialist who investigated the case, the agency reacted quickly to the tip. Forgie made a visit to Stockton to conduct a visual inspection and to interview Sievers, who told Forgie “he was not aware of any drums buried on the property.”

“Based on the findings of the initial visual inspection, the complaint was thought to be unfounded,” Forgie wrote in a letter to Sievers in October 2022.

It turns out that Sievers was either unaware of what was happening on his farm or he wasn’t being candid with the state inspector. A month after Forgie’s visit Roeslein executives got wind of the anonymous tip and sent in their own investigative team. There was ample justification for the company’s concern. The Iowa DNR also staffs an active Contaminated Sites division that is expert in federal and state statutes overseeing the disposal of toxic and hazardous wastes. Illegally disposing chemical wastes in buried barrels can be prosecuted as felonies, resulting in large fines and potential imprisonment.

Given such penalties, and anxious to protect its reputation and the large Climate Smart award it was expecting from the U.S.D.A., Roeslein’s inspection turned up a burial ground for barrels of waste. The company alerted the DNR. In an online meeting with Forgie and his colleagues on August 2, the company told state authorities that it found “2 blue poly drums, buried 3 feet down in an old burn pile area.” Roeslein agreed to voluntarily excavate the burial pit and dispose of the barrels.

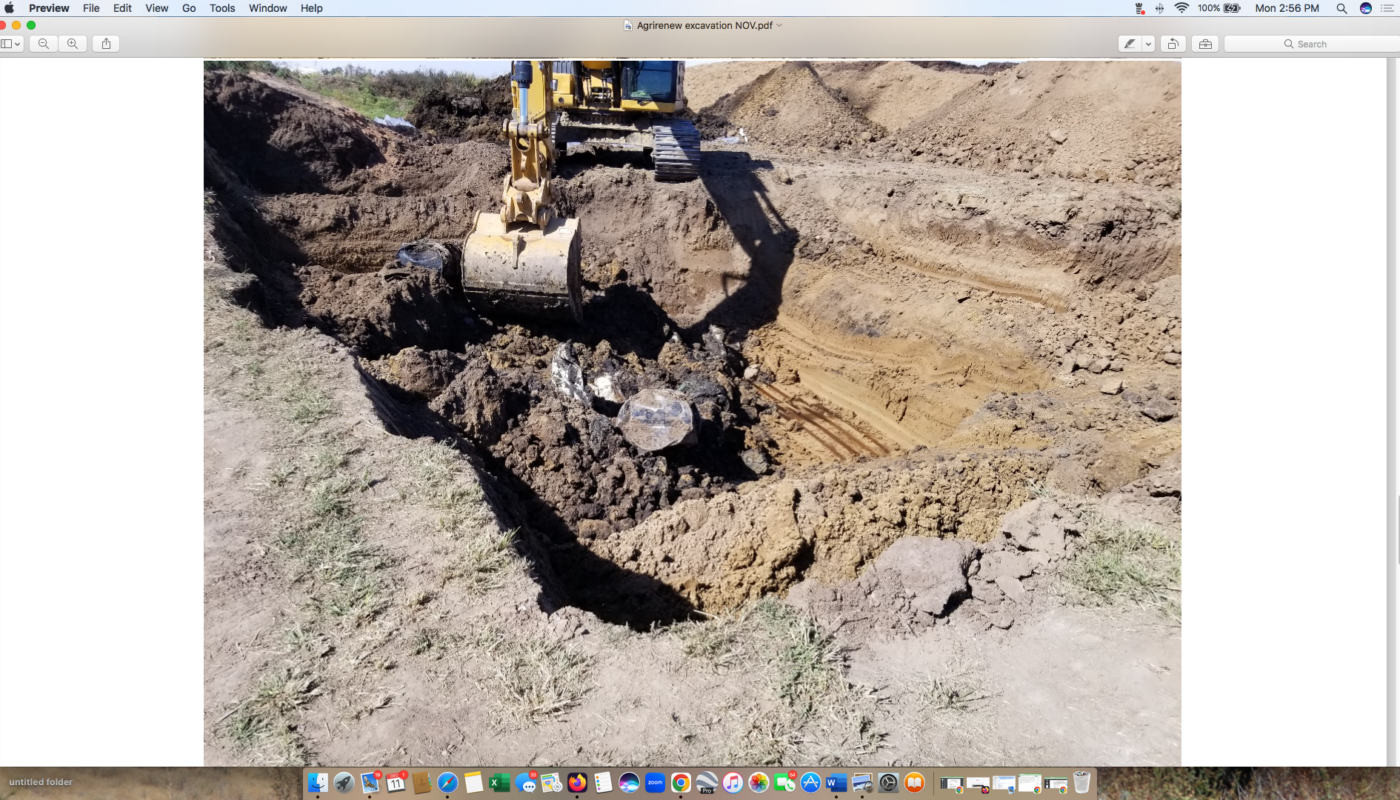

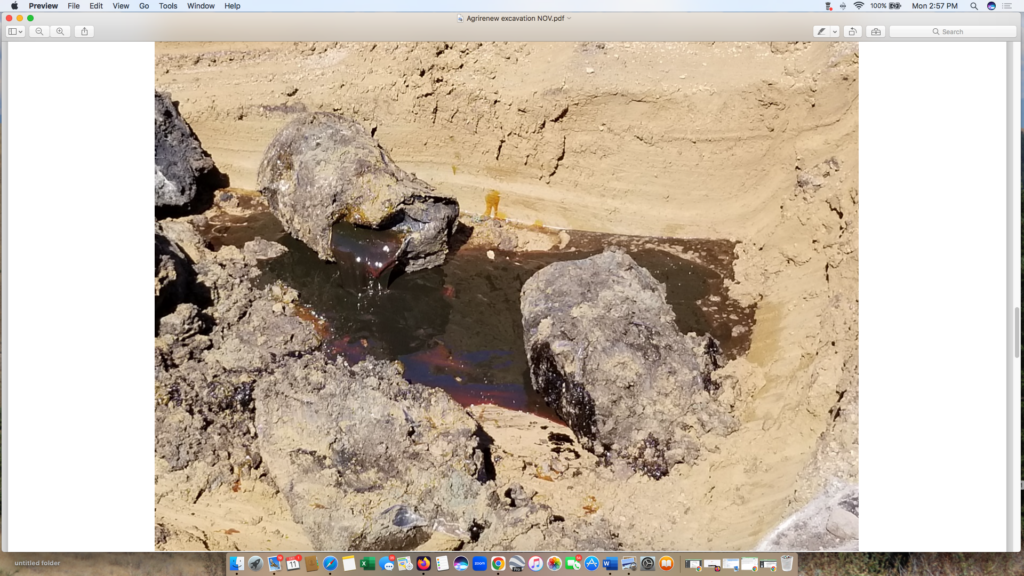

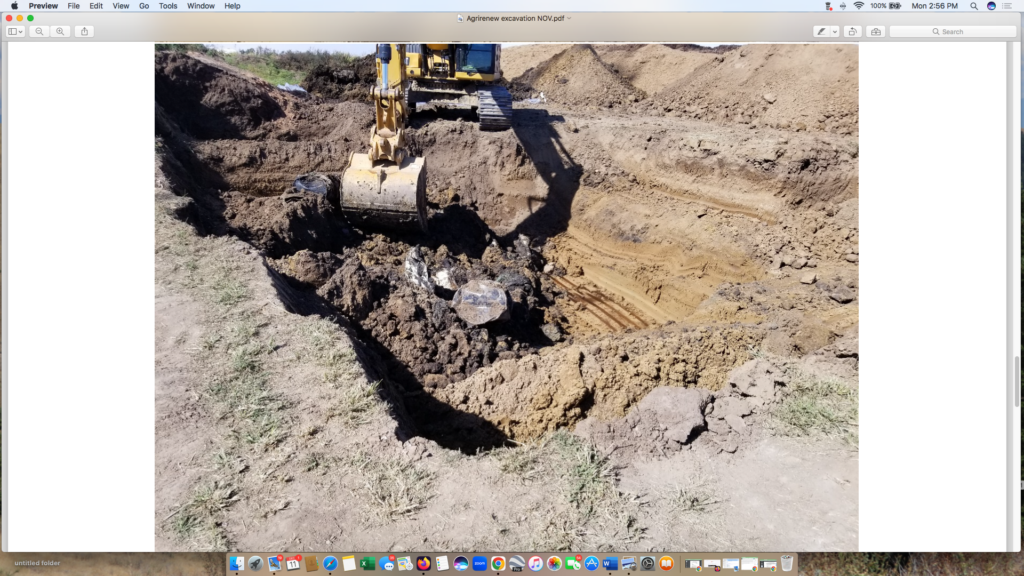

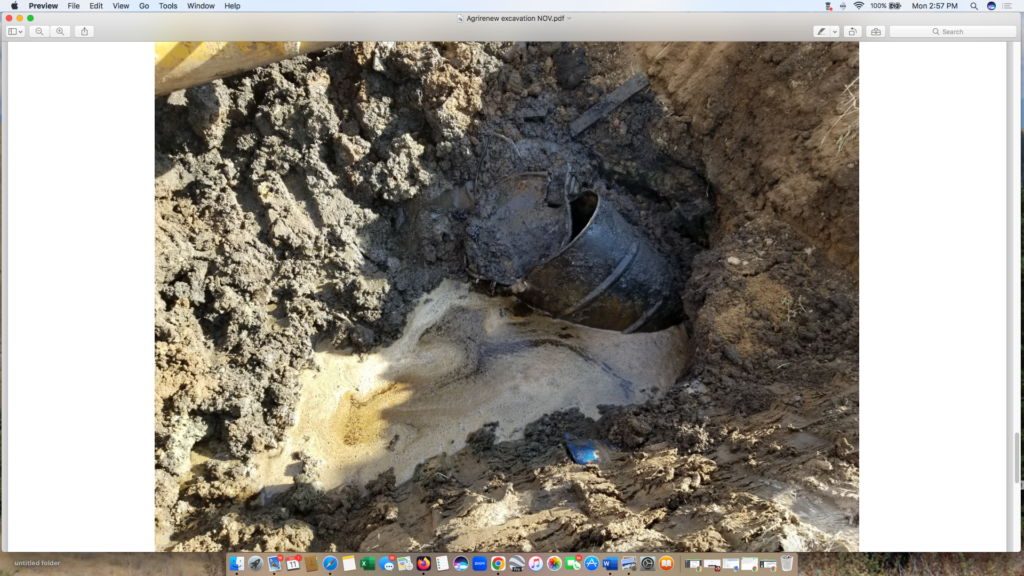

But the company’s assurance that the site contained just a few barrels turned out to be as fictitious as Sievers’ initial response to Forgie. On October 4, Forgie was at the farm to observe the cleanup. Excavators uncovered at least 20 drums buried in a pit 20 feet wide, 40 feet long, and 14 feet deep. “Many of the drums were not empty, but instead contained what appeared to be petroleum-based waste fluids,” he wrote. The administrative order issue by the DNR contained a more complete description: “A few of the drums that appeared early in the excavation contained a foamy liquid that had a very rancid, or rotten odor. Some of the drums deeper in the excavation area contained brownish-black fluids.”

And here’s where Iowa’s regulatory mettle dissolved and its allegiance to big agricultural companies took precedent. Neither Roeslein nor Sievers were required to sample the “brownish-black fluids” to determine what they actually were. Forgie said in the interview that the pit was unstable and too dangerous to take samples. “The pit was freshly excavated,” he said. “We didn’t want to get anybody down there and risk getting trapped. They didn’t take any direct samples of the contents of the drum.”

Instead, the state accepted Sievers’ explanation that the barrels contained soy lecithin, a non-toxic feed additive. That designation enabled the DNR to treat the buried barrels as a solid waste, and not a chemical waste infraction even though soil samples taken from the burial site showed low levels of barium in groundwater and soil, and traces of chromium and lead in the soil. “No petroleum-based substances were found in samples,” the state determined.

The Iowa DNR issued an order of violation and the $5,000 fine for “dumping or depositing any solid waste at any place other than a sanitary disposal project.” Bryan Sievers signed the order on November 30, 2023.

— Keith Schneider