CENTRAL LAKE, MI – There is no sprawl in Central Lake, a northern village of 942 residents in magnificent Antrim County. At this time of year rows of feed corn await harvest and the green white pine and multi-colored hardwood forests pour down the hillsides to the deep blue waters of the lake that gives the village its name. (see pix above and below)

Central Lakes possesses an asset all-too rare in American communities – a clear center. But there are a number of empty storefronts, and a closed pizza restaurant and bar, that signal the economic emergency that has engulfed this region and much of the rest of Michigan has gotten no easier and actually looks to be getting worse. There is no scenario of aspiration evolving in the governing sector. The dark windows reflect a persistent inability to reckon with the era of stalemate and stagnation that is scarring this state and the rest of the United States.

One seemingly insurmountable problem here, as in so many other places, is that residents and the people they elect to state and national office are consistently unable and unwilling to make a fateful choice. That is the decision between the grim consequences of austerity, and the commanding logic of investment, entrepreneurism, and imagination. People are confused about the appropriate role of the public sector in encouraging private sector development. They hear from one party that government is the problem. They hear next to nothing from the other.

And because people don’t know they also can’t fathom the complexities of winning the fierce contests in two arenas that require highly developed levels of definition and understanding.

The first contest is external. Technology, foreign competition, and terrorism have unnerved Americans. The nation’s customary feeling of command and control has been disrupted. Taking its place is a state of reaction that whipsaws between fear and thoughtless decisions that are eroding the country’s self-confidence. The nation’s two century-old democracy suddenly seems immature, and its leadership both ineffective and reckless.

The second confrontation is internal. How does a community like Central Lake reach agreement on a development and business retention strategy when all people want to do is rant about ideology. And while the clashes escalate the town arrives at the same economic dead end of argument and grievance that has damaged so many other places in the United States. Paraphrasing New York Times journalist Tom Friedman, Central Lake is not just facing a few tough years. It may be contendingwith a bad century.

To be fair, it’s understandable that Central Lake citizens and a good number of its elected officials exercise caution and seemed so ready to hug tightly to the old patterns and economic ideals of the 20th century. For a long time those tools worked. The prevailing market conditions shaped a national purpose, a big target of where to aim, and a clear picture of what economic success looked like.

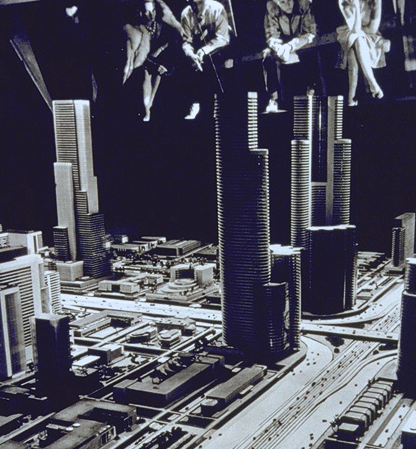

That picture, which came to be known as the American Dream, was first introduced at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in the General Motors-sponsored Futurama exhibit. Futurama was a huge diorama of a highway-heavy, congestion-free, car-dependent, time-efficient, leafy green all-American suburban pattern of development that no one had ever seen before.

A Pattern of Civilization Fit For One Century That No Longer Works

The exhibit was a smash. Visitors were transported in egg-shaped seats on a soaring conveyor belt across a landscape of innovation, creativity, and optimism. What astute observers recognized was that GM’s new American geography needed enormous public investments in the roads, sewers, education, research, planning, and industrial infrastructure to make it reality.

The shining and mobile American way of life displayed by GM, moreover, was eminently achievable. It fit the essential market opportunities of its time – cheap energy, low cost land, moderately rising population, competitiveness in core industries, rising family incomes, growing government wealth, and the willingness of taxpayers to invest in the nation’s future.

Over the next two decades voters elected to Congress and the White House lawmakers of both parties who cooperated in steadily enacting big and expensive bills – the GI bill to educate veterans, lending bills to put them in new homes, the 1956 Highway Act to start the Interstate system, water and sewer spending bills, research grants for engineering – that changed the way America looked and functioned.

The problem Central Lake and the rest of the country confronts is that the American way of life no longer fits the times. All of the underlying market trends that produced the drive-through economy have flipped. Energy prices are high and steadily rising. Land is expensive. Entire core industries, and millions of jobs, have moved beyond our borders. Median incomes, in real dollars adjusted for inflation, have fallen 10 percent since the late 1990s. Governments operate with enormous deficits. Taxpayers are unwilling to invest in a collaborative future.

The result is a town and a nation with fewer choices and less mobility, a nation that is uncharacteristically hesitant and afraid. And while ideologues on all sides shout past each other, and make holding office a thankless and grueling experience, the real danger in our governing circles is the entrenchment of the politics of stasis. Doing nothing. Holding the line. Not deciding. Not acting.

On a beautiful fall day, warm and clear and colorful, that outcome seems so sad.

— Keith Schneider