KUALA LUMPUR — I had no idea what to expect from Malaysia when I accepted an assignment from Mongabay to report on the consequences of a prodigious wave of infrastructure development that is remaking this country’s economy and geography. What I’ve found is a nation contending, like so many others, with political disruption, but fully competent to develop the new muscles and bones to support the contemporary needs of this century.

People here are suspicious of their leaders. But the questions about corruption and competence of Malaysia’s political leadership are infinitely easier to answer than those being asked in the United States about America’s ruling class. The notion that the U.S. is exceptional isn’t a ruse. It’s just changed radically in the last several decades. We’re such a rich nation. But we don’t deploy our wealth to enhance civic well-being. The U.S. is exceptional now for the miserable way our political system has crumbled, our public schools and infrastructure have deteriorated, our sense of confidence and purpose have weakened.

The American century likely ended on 9/11. The Asian century began soon after. It’s more than apparent in Malaysia.

For a journalist who’s spent a decade reporting on ecological and economic transformation around the world, I have one overriding observation about Malaysia. Malaysia is different than China, India, Mongolia, the Philippines and several more countries that are determined to achieve western-level measures of growth. Malaysia did not wreck its land, water, air, and marine environments getting there.

Clean rivers still flow here. Half of the country’s tropical forest cover is intact and will remain so under commitments Malaysian leaders made in the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. Near shore marine environments have not been ruined by mining disasters, as they were in the Phillippines, or soiled in tides of fetid urban wastewater, as they have been in India and China.

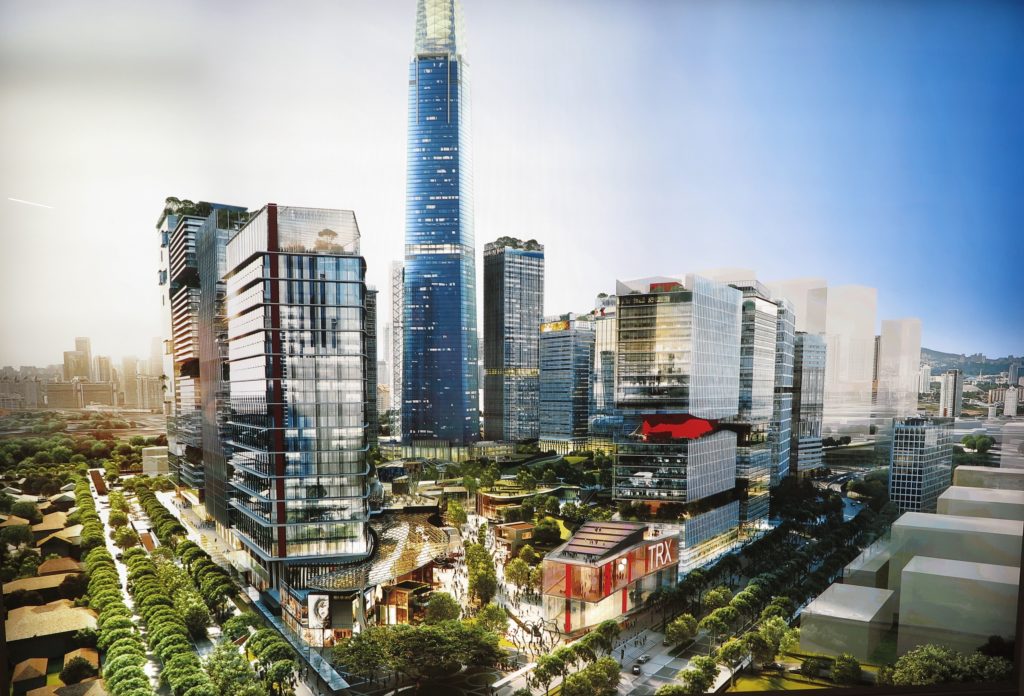

Malaysia has had a lot of help. Japan and Korea financed a wave of development in the 1980s and 1990s that began to turn Kuala Lumpur, the capital city, from a developing world backwater to a showcase of contemporary tall towers, shopping malls, clean neighborhoods and excellent electrified public transit.

China is now investing even more in the second decade of this century. It is helping Malaysia finance and build new ports, a new electrified urban and national rail transport network, new industrial manufacturing bases, colossal residential and office developments, and clean energy electrical generating stations to thrive in a warming, hydrologically unstable world.

I’m impressed. A fast train carried us directly from Kuala Lumpur’s distant airport to the central city. It is every bit as swift and comfortable and reasonably priced as the train from Stockholm’s distant airport to Sweden’s capital city.

Metro service trains and buses are cheap and fast and convenient. So are the GRAB taxis, hailed online like Uber, which arrive quickly and cost less than $2.

There are other details about this country’s rising stature in Asia that bear notice. For instance, public bathrooms are clean. Alleyways are free of litter and debris. So are streets and highways. Highway medians and rights of way are landscaped, and shrubs are kept neatly trimmed.

Elevators to convey passengers to public areas, like train station platforms, work. So does every escalator I’ve seen. Not a single one was out of order.

The streets can get crowded with vehicles but drivers don’t honk. This is the first Asian city I’ve been in that isn’t a cacophony of car and truck horns.

There is an orderliness in Malaysia that’s cultural and directed. Rental car companies forbid eating in their vehicles. Highway toll plazas are cash free. You buy a trip card from any fuel station and “Touch and Go” at the toll booth. People are pleasant, well-mannered, and exceedingly helpful. Malaysian meals are good, especially seafood.

Lastly, there is no sense of menace. It’s illegal to have a gun in Malaysia without a license. Violators face long prison sentences if they are caught. Drug dealers are prosecuted and some are executed. You don’t walk into a mall, or stroll in a park and worry about some Malaysian nut case with an assault weapon. They essentially don’t exist here and nobody is ranting about defending the public’s right to have one.

My sister wrote to me here, reacting to my Facebook posts. She expressed surprise at how cosmopolitan, contemporary, colorful and interesting Malaysia seemed from my photographs.

Let me tell you, I’ve been delighted by what I’m finding here. It’s exceptional.

— Keith Schneider

The biggest cave, reachable after climbing 272 steps, is as big as New York’s Grand Central station. (Photo/Keith Schneider)[/caption]

The biggest cave, reachable after climbing 272 steps, is as big as New York’s Grand Central station. (Photo/Keith Schneider)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_7032" align="aligncenter" width="525"] An idol guards the entrance to Batu Caves, reachable after climbing 272 steps. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

An idol guards the entrance to Batu Caves, reachable after climbing 272 steps. (Photo/Keith Schneider)