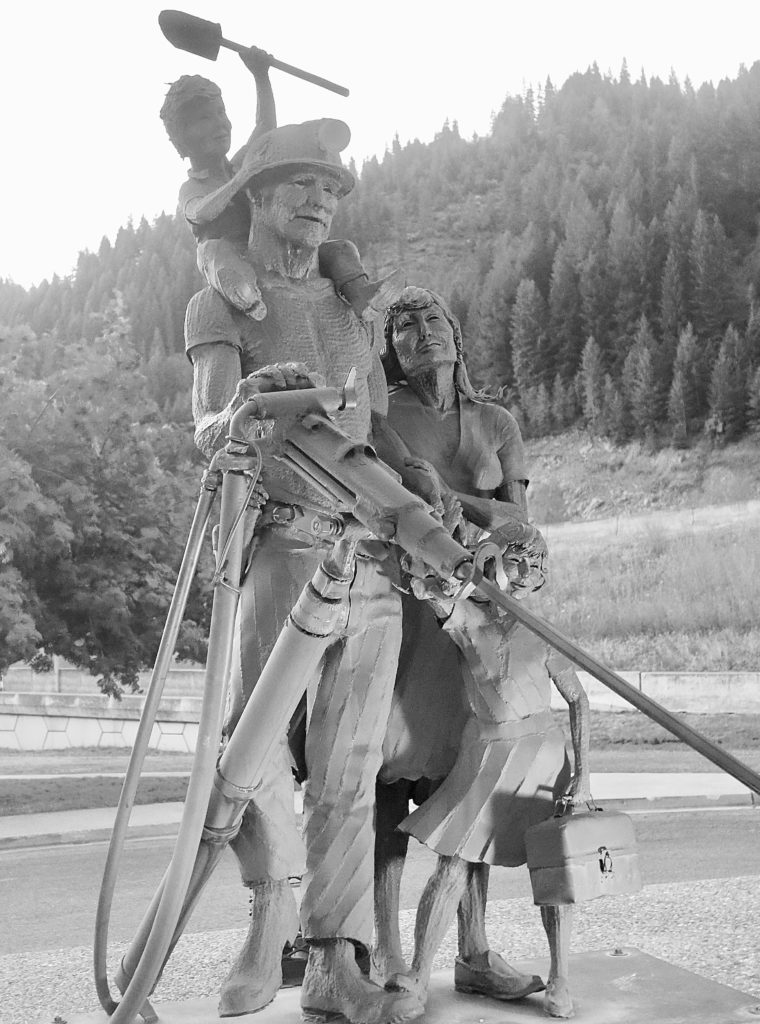

putting 2,000 people out of work and ending a century of mining prosperity in northern Idaho. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

KELLOGG, Idaho — Completed at a cost of $30 million and opened in 2004, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes cuts a paved path across Northern Idaho, from Mullan to Plummer, following the course of a long-abandoned Union Pacific line. One of the country’s magnificent rails-to-trails, it’s ordained by natural flourishes that exist in abundance in this part of the Mountain West — tall peaks, forests of fir and spruce, big farm fields, wetlands, clear blue and emerald waters.

Still, what I found more intriguing during a six-day cycling trip in July was that so much of the 73-mile trail is flanked by manmade shrines to a 100-year legacy of industrial exploitation, union organizing, and mortal danger that started in the 1880s. Nearly 40 years of rigorous data-gathering, legal wrangling, prodigious investment, and environmental restoration followed. Just like coming upon the broken wooden bones of shipwrecks on a stormy coast, the paved path unveils a collection of silver, lead, and zinc mines cut into steep slopes. They once were among the world’s largest and deepest. Mouldering processing and administrative buildings still stand in the shadows. Close by are immense piles of contaminated rock and soil, contoured and mounded in precise block-like geometry and capped in table-flat meadows of tall yellow grass.

I never intended to write anything more than a travelogue about the trail and the ride with my wife and daughter, which was lovely. But I’ve also made a living telling stories about people and communities in North America and on five more continents where industries operate — most poignantly about how time, technology, changing markets, and evolving public sentiment converge to produce the drama of memorable consequences.

Barely an hour’s drive east of Coeur d’Alene, this region of mountains and rivers and small towns that once housed thousands of miners and their families are the stage and central characters in a saga of brawny mineral development, industrial innovation, environmental renovation, and economic reckoning that was entirely unexpected. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes cuts a clear path through a great story that has enduring relevance.

It starts in the centuries before the first white miners reached the tight valleys and swift streams that rushed out of the Coeur d’Alene Mountains in the 1860s. Much of the region now known as Idaho’s panhandle was settled by the Lemhi Shoshone. Sacagawea, who guided the Lewis and Clark Expedition from North Dakota and across Idaho in 1804 and 1805, was born to the same tribe, whose members masterfully fished the fast-moving streams and hunted bison and elk in the steep mountains cloaked in tall trees. Spanish explorers introduced the 8,000 Native Americans in the region to horses. The Lewis and Clark expedition crossed the mountains 200 miles south in 1805, and a bit later, mountain men introduced trapping techniques.

The pastoral and ancestral calm ended pretty quickly in the 1850s and 1860s when placer miners, who found gold in the stream beds and banks, introduced rapacious practices and conflicts. The first wave of placer miners was replaced in the 1880s by hard rock miners who steadily cut deep and long drifts into the mountains to extract a motherlode of silver, zinc, and lead. Dozens of mines opened, along with crushing and processing mills. A rail line was constructed along the banks of the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River to haul people, equipment, and ore. Men and their families migrated to Shoshone County where the trees were stripped from the hillsides, the air was black, the rivers were mucked up with mine spoils, and much of the limited flat ground was inundated under blasted rocks and waste.

The string of towns and mines came to be known as the Silver Valley, recognizing the most valuable mineral. But a more accurate name could have been Black Basin, an honest acknowledgement of the presiding color of the air, water, ground, and streets polluted by mine drainage and atmospheric fallout from active smelters. In a century of gross imbalance between the economy, the environment, and public health, mine revenues outweighed any other consideration. And there was huge money to be made. Over the 100 years that it operated at peak and near-peak production, Silver Valley mines and processing plants produced more valuable metal than almost any other place on Earth ever – 1.2 billion ounces of silver, 3 million tons of zinc, and 8 million tons of lead. Total value in current dollars: over $50 billion.

Given such wealth, and the stingy manner with which it was hoarded by mine owners, the Silver Valley also produced a century-long epic of labor unrest, natural calamity, workplace tragedy, and environmental injury matched by no other region in the United States, and perhaps anywhere else, for that matter. A vicious war over pay, workplace safety, and unionization between the miners and mine owners lasted over a decade in the 1880s and through the 1890s that involved bombings, kidnapping, and murder before being quelled by federal security forces. A former governor of Idaho was assassinated in 1905 by a bomb. Mine union organizers were charged with the murder but acquitted in 1907.

Three years later a monstrous wildfire, one of the deadliest in U.S. history, burned through 3 million acres of northern Idaho and Montana, destroying much of Wallace, Kellogg, and other Silver Valley towns and killing 87 people. In 1972, a fire erupted in the Sunshine Mine outside Kellogg, killing 91 miners in one of the worst mine disasters in the U.S. Later that decade air pollution control equipment failed at the valley’s major lead smelter. The company continued to operate, contaminating air and ground so egregiously that lead levels in children soared to concentrations that affected their central nervous systems. And in 1981, as federal health authorities closed in to address the health risks, mine safety inspectors combed the drifts for violations. Global markets capsized, and the Bunker Hill lead mine closed, taking with it 2,000 jobs.

The valley’s population, employment, per capita income, and prospects fell like a barrel of lead heaved over a cliff. Over 6,000 people left, a third of Shoshone County’s residents. The region has since been among Idaho’s leaders in rates of unemployment, poverty and suicide, and at the bottom of the chart in income. Though three big mines are still in operation, the Bunker Hill closing ended one of the West’s signature eras of raucous industrialization.

In its place, an entirely new epoch emerged, one just as characteristically American, and likely to last just as long. Call it the first green new deal, a never-before-tried pact between the United States, industry, and citizens intended to set a new equilibrium between economic, environmental, and public health interests. For the first time, polluting industries would be compelled to clean up after themselves. The Silver Valley was one of the first test cases, an early arena for lawyers, prosecutors, and activists to apply clean up provisions of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, otherwise known as Superfund.

Signed in December 1980, the law was a response to the public health threats and ecological messes produced by companies across the country that buried, hid, drained, and disposed of their toxic wastes in ways that celebrated the efficiency of the free market economy but utterly lacked respect for human and natural health and life. The law was prompted by the discovery of seeping chemical wastes in 1978 at the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, N.Y. Love Canal simultaneously alerted the country to the proliferation of unregulated toxic waste dumps, and the systemic result of the myriad ways that executives distanced themselves from the dangerous byproducts of manufacturing almost everything modern society used.

The new law, administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and state environmental departments, provided powerful legal tools to recover the cost of excavating, treating, and disposing such wastes from industrial companies. It did so by giving government lawyers the authority to 1) put particularly dangerous waste sites on a National Priorities List for urgent remediation, and 2) recover monetary damages for expensive cleanups if they successfully linked the wastes to deep-pocketed polluters.

Though unwieldy in its application, and often consuming years of litigation between the discovery of a waste site and its eventual cleanup, the nearly 40-year-old law has recovered tens of billions of dollars to close and safely reclaim thousands of toxic waste sites across America. We are a safer people because of the Superfund.

In 1983, the EPA put the Silver Valley on its National Priorities List, commencing one of the country’s largest, most ecologically complex, and most expensive Superfund projects. Four decades later the project, named after the Bunker Hill mine, has expanded from an initial 21-square-mile zone to scrape lead-contaminated soil from 3,500 properties in and around the city of Kellogg, to a more than 1,500 square-mile region of mine sites and sediments permeated with heavy metals. Some 2,500 more lead-contaminated yards have been excavated, and work is ongoing to identify and halt the flow of arsenic, lead, and other toxic metals from watersheds across Northern Idaho into the Coeur d’Alene River and Lake Coeur d’Alene.

The project over the years attracted ample resistance from some residents and local government leaders for the scale of excavation activities, costs, science, and the lingering presence of federal managers. The project also is seen as a demoralizing curb on new development because of the stigma of its toxic foundation.

But the project also is supported by state and local elected leaders and many of the region’s businesses and families. The reason is that what started as an ambitious and disputed project to protect health and natural assets has expanded over four decades into a jobs and economic recovery program. It could reasonably persist for another 20 or 30 years. The Bunker Hill Superfund project, in sum, is a study in the long-term economic relevance of practices meant to safeguard natural systems as a replacement for heavy industry dedicated to dismantling them.

and capped in table-flat meadows of tall yellow grass near Kellogg. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

I’m no stranger to the Superfund. As a young writer I reported on how administrators at the Environmental Protection Agency in the first years of the Reagan administration illegally directed federal dollars to clean up toxic sites in Congressional districts that supported the G.O.P. Later I visited a Superfund site in Arkansas where the E.P.A. decided to burn thousands of tons of soil contaminated with dioxin at a cost of more than $100 million. The soil had already been excavated and stored in big barrels in a hastily constructed warehouse. I reported that the E.P.A. remedy was a rebuke to reason and science. For every barrel of dioxin-contaminated soil burned in the incinerator, the government received two barrels of slightly less dioxin-contaminated ash that had to be stored in a second big warehouse.

In another Superfund site in Mississippi I reported on how thousands of tons of soil contaminated with pine tar and pitch — wastes from a Naval manufacturing site during World War Two — were being excavated and transported by a fleet of trucks to a waste recovery site in Louisiana. Thousands of loads of soil were being dug up by backhoes, emptied into trucks and hauled across the Mississippi River at a cost exceeding $40 million. The biggest danger from that site, I found, wasn’t exposure to the soil. It was from being killed or injured in a traffic accident with one of the dump trucks.

The Bunker Hill Superfund project is a much different scenario. During the time I spent in Idaho, and in the reporting I’ve done online and by phone in the days since, it initially seems to me that the Bunker Hill cleanup represents a formidable example of the original intent of the Superfund program. The first and most significantly risky features of pollution have been excavated and contained around Kellogg at a cost of $263 million. The work took over a decade. More work is proceeding in surrounding communities, especially to stem heavy metal drainage into Lake Coeur d’Alene. The government recovered sufficient financial support to undertake the project. I’m pitching The New Yorker to assign me to dig deeper.

What I saw, though, was impressive. The hillsides have been replanted and new forests are growing. Rivers run cleaner. Kellogg, Wallace, and Harrison are holding their own. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes was more than a pleasing bike ride. It turned out to be a compelling tour through an economic and environmental transition unique to Idaho, yet so distinctly American.

Sounds like you “dug deep” on your trip out to the northwest, Keith, as you usually do. Good work! Hope you get the Times to let you go deeper!

I lived there the in 1965 – 1966. My dad worked the mine.