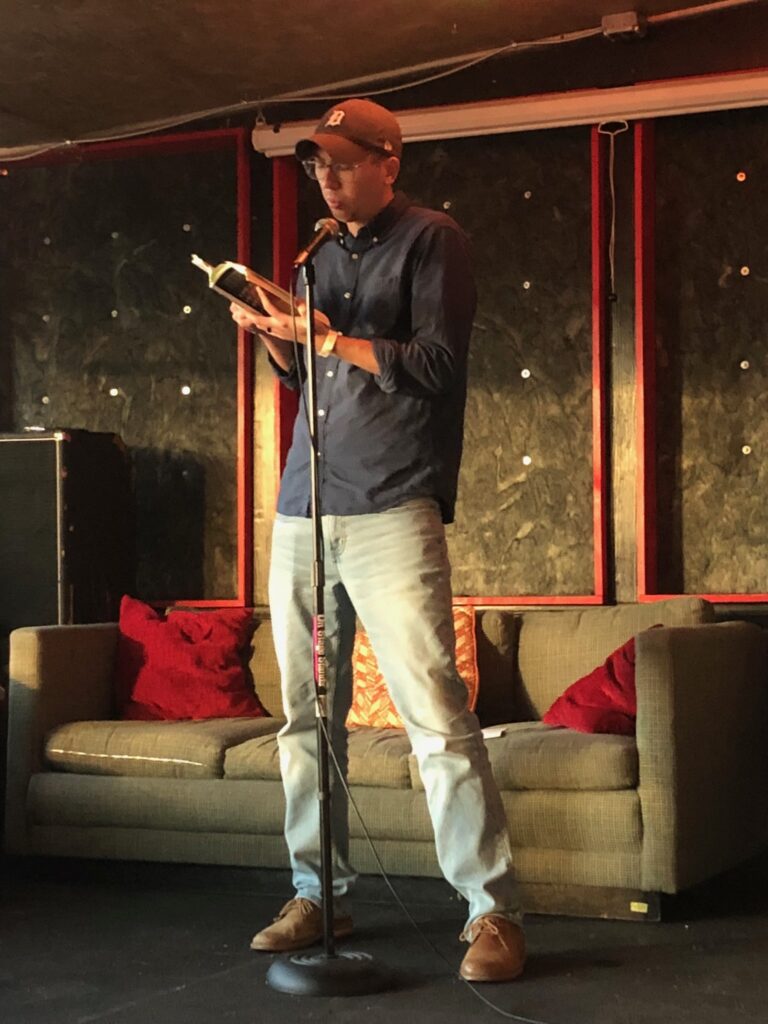

his national award-winning first book of poetry. (Photo/Mara Bates Rushton)

“When the celestial passes close everybody will stop and want to be the comet.

Maybe then the type of mattress won’t matter.”

Brandon Rushton from What If There’s Something Out There

BENZONIA — Brandon Rushton, who is 33 years old and a poet of national distinction, writes with the awareness and power of a young man determined to diagnose America’s endemic bafflement. His collection of essays and poetry, “The Air in the Air Behind It,” was published in September by Tupelo Press, which also honored Rushton with its prestigious Berkshire Prize for an outstanding poet’s first book.

The prize selection committee and judge demonstrated keen awareness of Rushton’s capacity. He’s a chronicler of deconstruction. His poetry encompasses the millennial generation’s distress about the century’s disembodied geography, the pretension of stability and security amid the reality of profound disruption. Never mean-spirited, Rushton’s pursuit is to see everything anew with eyebrows-raised, and often with the lip-curling disappointment of people his age.

“All the things we vowed to change, changed without us,” he writes. “It was like mankind and like mankind it was all unmemorable. It felt important. To that importance we applied a plaque, the last relic of our remembering. Seriously, what are we to make of the landmarks.”

Where does such acute inspection come from in a young man born in Flint and raised as a single child in Clio, Michigan by a mother who was a computer lab teacher and a father who worked for 35 years in GM’s Truck and Bus Assembly plant in Flint?

Beyond Rushton’s intelligence and sensitivity the answer is plain enough. Until he graduated in 2012 from Saginaw Valley State University with a degree in history and creative writing Rushton spent virtually all of his time in two worlds in conflict. The first was his secure, close, adoring family living in a home built by his father a few minutes away from another Clio home where his grandparents lived. Lawns regularly mowed. Vacations at the family cabin. Fishing and hunting along the magnificent Au Sable River in Up North Michigan close to where Hemmingway spent his summers.

The second was the cauldron of disruption and anxiety occurring everywhere else in the world. When he hadn’t even turned six years old in 1995 Timothy McVeigh, a product of the Michigan Militia, bombed the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. When he was 12 the Twin Towers fell. Michigan lost 800,000 manufacturing jobs in the first decade of the century as GM and almost every other Michigan maker of consumer and industrial products closed plants and shipped jobs out of the state and country. State unemployment reached 15 percent during the Great Recession when Rushton was 19. Clio lost 600 residents, a quarter of its population. And then came the moral MAGA void, the years of unprincipled allegiance to what had always been the principles of facts, truth, family, and rights that America once regarded as sacrosanct.

All of this, and much more, served as ingredients for the rich creative soil from which Rushton’s artistry blooms. “So then lastly the land allows us this,” he writes, “the children who insist on sprinting through whatever light is left. All of the parents making their way out of the water, afraid of what they’ll miss. “

I encountered Brandon Rushton for the first time in the late spring of 2010, a few months after my daughter, Mara Bates, met him during a college spring break trip to Florida and informed us she was developing a relationship with a poet. I followed his work in the years since, admiring his skills as a writer and his depth as an observer. He’s a classic Michigan man. Quiet. Patient. Self-effacing. I’ve only been with him twice when he wasn’t wearing a baseball cap, visor turned forward. The first was the day they married in 2018. The other occurred last spring when Brandon delivered the most stirring eulogy I’ve ever heard in honor of his father.

Following a post teaching writing at the College of Charleston in South Carolina, Brandon joined the faculty at Grand Valley State University as a visiting professor of writing.

Both Gabrielle and I were raised in families that marked big events with celebrations. The publication of Brandon’s first book qualifies as a big event. So on the last weekend of September, Gabrielle and I were joined by Mara and Brandon, his mother Joyce Rushton, and 22 other friends here at the house to hear Brandon read from The Air in the Air Behind It. We followed the reading with a sit down dinner. Keeping Covid risks in mind we gathered under pop up tents, and set dinner on tables in the garage.

The weather held and the event was fitting and memorable just like Brandon’s poems. I’m not the exquisite master of language and concept like my son-in-law. But I am a writer mindful of detail and data. Brandon read beautifully and sold 52 books that day. Terrific for any writer.

— Keith Schneider