There have been 50 Interior secretaries since the department was established in 1849 and President Zachary Taylor named Thomas Ewing its first secretary. On Tuesday, September 21, 2010, in a Washington dedication ceremony that brought Republicans and Democrats together for an all too rare moment of inspiring reflection, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar formally declared that his predecessor, Stewart Lee Udall, was the “greatest secretary of the Interior in United States history.”

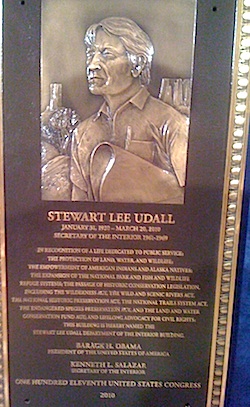

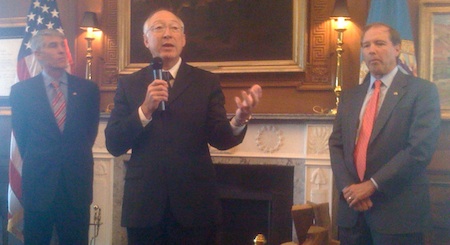

Salazar — in pix below with Senators Tom Udall (right) and Mark Udall (left) — delivered this insight a few moments before dropping a blue drape and unveiling the bronze plaque that will soon be affixed to the agency’s headquarters in Washington. In May, Congress passed, and on June 8 President Obama signed a bill that names the headquarters the Stewart Lee Udall Department of Interior Building. Joining Salazar on the Interior Department auditorium stage were a good number of Stewart’s large family including two sisters –Elma and Eloise; the two senators from New Mexico and Colorado; three more children – Lynn, Lori, and Denis; and a number of grandchildren plus wives and husbands.

In sports, the ultimate honor is to retire a star player’s number. In government, it’s naming the agency headquarters after its most distinguished leader. It’s a rare event. The FBI and Labor Department headquarters are named for leaders. The Senate and House office buildings also are named for honorable lawmakers.

Stewart Udall served as the 37th Secretary of the Interior from 1961 to 1969 under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and at a time when bipartisan values enabled Washington’s elected leaders to govern in the public interest. Stewart’s mission to more sensitively manage the nation’s resources even as he alerted the country to what he called the “quiet crisis” of pollution and degradation yielded a legacy of land preservation and environmental safeguards that changed the nation for the better. Stewart died on March 20, 2010 at the age of 90.

Each of the seventeen men and women who delivered remarks, song, and poetry at the dedication described in often funny, and always telling detail how Stewart’s life, and his work in and outside government, delivered to every corner of the nation parks, wild lands, natural rivers, refuges, clean water, clean air, arts, cultural institutions and justice. They also recounted how he did so with humility, reverence for beauty and prose, and a stubborn optimism about the promise of America.

Robert Stanton, the National Park Service director from 1997 to 2001 and the agency’s first African American leader, recalled how in 1961 Stewart purposefully recruited students from historically black colleges to work summer jobs at the Interior Department. Stanton heeded the call from “my secretary” and ended up as a seasonal ranger in Grand Teton National Park.

Lynda Johnson Robb, the daughter of Lady Bird and Lyndon Johnson, revealed to the more than 200 people that attended the ceremony, that “Mother and Stewart, you know, had an affair” and that “Daddy was so jealous because Mother was spending so much time with Stewart.” Her cheeky observation, of course, reflected the close relationship Stewart had with Lady Bird, who shared with the young Interior Secretary the same goals of conservation and stewardship. The two traveled together to parks in the west, said Robb, and down rivers on rafting trips.

Douglas Brinkley, the Rice University historian, noted that President Johnson, who Stewart served as Interior secretary for more than five years, deserved more respect and recognition for how his Great Society programs laid the foundation for the era of environmental policy making that occurred in the 1970s. And he noted that President Johnson, who was raised in the beautiful Texas Hill Country near Austin, also heard nature’s call of distress. “One day President Johnson called Stewart in his office,” Brinkley said. “Stewart, he said, I hear that Lake Erie is getting dirty. It’s dying. Is that true?”

Brinkley said that Stewart confirmed the lake’s diminished condition and explained that the Interior Department has wild lakes in its jurisdiction but doesn’t oversee water quality. “Stewart,” said Johnson, “do something about it. When I think about dirty water I think of you!”

Patty Limerick, a historian at the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado, who was a friend of Stewart’s, described the breadth of his interests – the law, the arts, writing, the environment, government, politics, the West, commitment to justice — and his capacity to weave them into visible gains for the country. She asserted that of all the people who have served the United States in an executive capacity only Thomas Jefferson exceeded Stewart in so successfully applying all of his varied interests and skills in service to America.

I met Stewart in 1988 when I was a national correspondent for the New York Times and he was a private attorney working on behalf of uranium miners and residents of the West downwind of the Nevada Test Site who’d been injured or killed by exposure to radiation from the government’s atomic weapons production and testing industry. In many ways, Stewart’s 12-year battle for justice for American victims of the atomic bomb, which culminated in a 1990 law signed by President George H.W. Bush, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, was the most heroic work of his life.

That’s saying something since Stewart was a machine gunner on board U.S. bombers during World War Two, one of the most dangerous assignments. He took up the cause of justice on behalf of Americans who’d been put in harm’s way by a government operating a dangerous radioactive enterprise in suspicion and secrecy.

Rebecca Adamson of the First Peoples Worldwide spoke to Stewart’s fealty to Native Americans, including the Navajo miners injured and killed by exposure to low-level radiation from the mines. His official portrait, which hangs in the gallery leading to the Interior secretary’s executive office, was painted by Allen Houser, a Chiricahua Apache artist. The portrait of Stewart, with his long hair brushed by a western breeze, and slightly longer lines of the chin and higher cheeks than he had, is meant to wrap him in the ceremonial embrace of the Navajo and Hopi tribes. The portrait, which also includes the transcendent browns, and greys and reds of the Colorado Plateau, is the dominating visual image that graces the bronze plaque naming the Interior building in his honor. “The First Nation lost a hero when we lost Stewart,” said Adamson. “We mourn his death and what he meant to us.”

Senator Mark Udall, Stewart’s nephew and son of Mo Udall, Stewart’s brother who he adored, provided some of the most fitting comments about his uncle’s stubbornness and stamina. In short, when Stewart set his mind to a goal there was no stopping his progress, whatever it took. If the Supreme Court was arrogant enough to deny downwinders and miners justice, Stewart would take it to Congress and win compensation for the families and a formal statement of apology from the U.S. government. “I never thought Uncle Stew would ever die,” said Senator Udall.

The last breath left Stewart Udall on the first day of spring this year. Yet as long as there is a United States of America, everything that Stewart did for the land and its living communities, wild and settled, will pulse with life. Denis Udall composed a song in his father’s honor, performed by a grandson, Jonah Udall, that made the same point:

He hiked canyon trails; ran rivers, too.

Climbed glaciered mountains just for the view.

If when we die, we go somewhere.

I bet you a dollar, he’s walking there.

Has anyone seen my old man?

Has anyone seen my dad?

Look where the mountains meet the sea,

And bring him home to me.

— Keith Schneider