HONOR, Michigan — From the place where it slips out of Lake Ann in Benzie County’s northeast corner, Platte River haunts a landscape of forest and open fields, steals past this village of 330 residents, crosses a mighty and silent wetland, fills a big lake, and then, nearly 30 miles from where it started, reaches a curved sand inlet where it empties into Lake Michigan. One of the 49 blue ribbon trout streams in Michigan’s lower peninsula, the Platte’s clear waters sparkle in the sunlight of a blue sky day. Cedars along the banks open their branches, as if to salute the splendor.

Still, there’s considerably more to the river’s story than its compelling beauty. In the 160 years since the watershed was settled by immigrants from the East Coast and Europe the river has flowed through three distinctive eras in Benzie County. The decades of rapacious logging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distinguished the first. That was followed by a half century of healing the waters and the forests, helped by the thousands of red pine seedlings planted by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps. The third era, when Benzie’s restored natural character inspired public policy to protect it, opened in the mid-1960s and has been unfolding ever since with increasing urgency, intelligence, and commitment. The banks of the Platte River, logged, healed, and now secure, have served as a stage for every era.

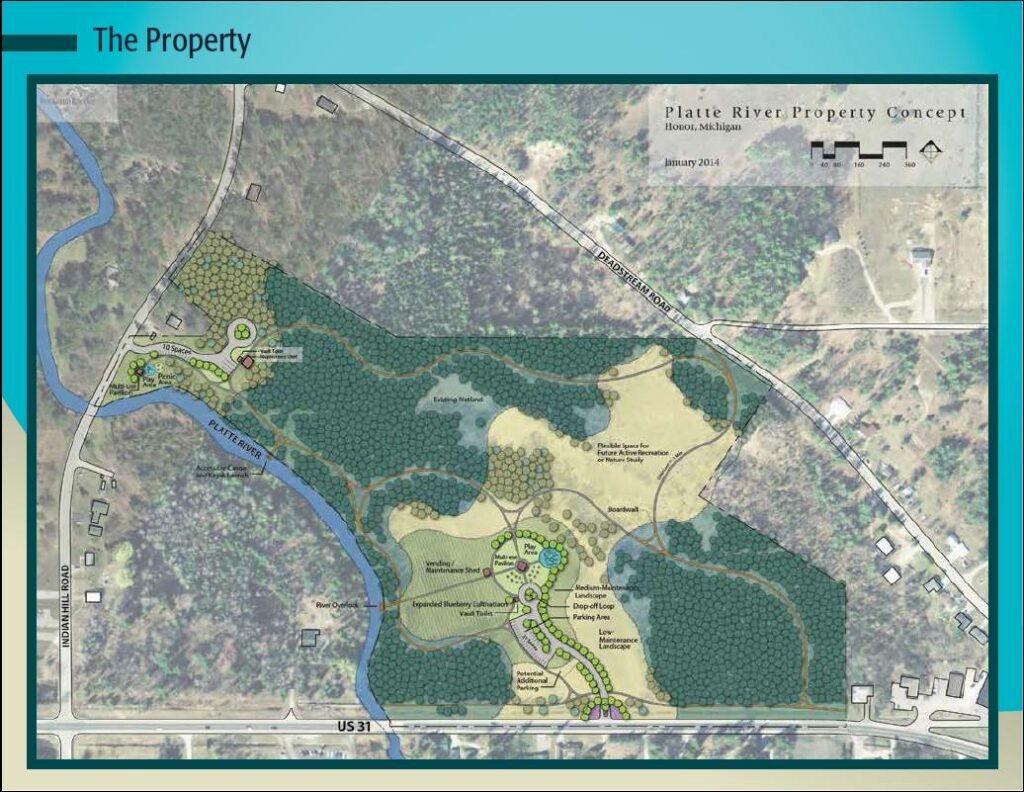

On May 18, 2024, a new act in the drama occurred when the Honor Area Restoration Project (HARP) culminated nearly a decade of citizen engagement and a keen public-private financing strategy and formally opened Platte River Park. The 52-acre expanse of forest, blueberries, and meadow flanks 1,550 feet of undeveloped riverfront. Platte River Park adds to the legacy of stewardship that’s helped make Benzie the greenest county in Michigan.

Before illustrating the steps that led to the new park let’s briefly describe those other environmental successes along the river. In the late 1960s, under the leadership of Howard Tanner, a fisheries scientist and director of the state Department of Natural Resources, the coho, chinook, and steelhead fishery launched from the state hatchery along the Platte just north of Honor. The purpose: curbing the alewife plague soiling Lake Michigan beaches.

In 1970, Congress acted on the idea from former Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and established Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, which protects the last miles of the river.

The Conservation Resource Alliance, led by Amy Beyer, raised state, federal, and private funds since the 1990s to rebuild road crossings and take other measures to halt erosion along the river. In the 2020s, the Platte Lake Improvement Association, led by Wilfred Swiecke, completed a 40-year campaign to clear Platte Lake of an annual toxic algae bloom. The Association won a court victory that compelled the state salmon hatchery upstream to change its fish feeding and waste management practices to dramatically reduce phosphorus discharges that caused the blooms. Platte Lake is the only major water body in Michigan, and one of the very few across the country, where harmful algal blooms were solved in this century.

All told, the conservation initiatives along the Platte River are important chapters in the meta-narrative that’s developed in Benzie County over the last half century. Nature’s healing of forests and waterways damaged by the 19th and early 20th century logging era merged with the local, state, and national environmental protection policies since the 1960s. The consequence is an uncommonly beautiful county that’s the foundation of a flourishing economy, a place where people act on opportunities to safeguard the land, the waters, and their small towns.

In every way imaginable Platte River Park fits into that story. It genesis was a public meeting at the Platte River School convened in 2011 by the Honor Area Restoration Project to decide on community economic development goals. Formed a year earlier by Honor residents Ingemar Johansson and Bruce Wilde, the Restoration Project sought to energize business in a community disrupted by the Great Recession in 2007 and 2008.

Clearly, Johansson and Wilde weren’t the only residents interested in that goal. The meeting attracted 150 participants who reached consensus on two salient projects. The first was renovating Honor’s streetscape, including a walkway from the town center to the shopping plaza south of town. The second was leveraging the magnificent reach of the Platte River close to the town center as an economic asset.

No one was clear at the time what that really meant. In 2017, though, Esther VanHammen, the owner of a cottage resort on Platte Lake, alerted the Restoration Project that Oral Kuck’s big parcel along the west bank of the river was on the market. Kuck was a much-loved character in Honor, who was born in 1910, and spent his life in the house built, and on the land developed, by his father, J.C. Kuck. The younger Kuck farmed blueberries and tended bees. Before he died in the 1990s he helped Kirk and Sharon Jones get started on their Sleeping Bear Farms honey business in Beulah.

“Esther came to us and said, ‘Hey, do you guys know about this property that’s for sale? Wouldn’t that just make a great public park?'” said Johansson in an interview. “So we took her word and went over to look at it. She was so right. Look at this — 52 acres, 1500 feet or river frontage. Perfect for a park to highlight the Platte River. That’s how that it came about. She had the vision for this early on.”

VanHammen’s alert and the availability of the Kuck farm came at a good time for HARP. Already seven years old, the citizen group formed a capable board, recruited a peerless Manistee-based fund raiser named Tim Ervin, and established itself as a community facilitator for new projects in town, including eight new units of affordable housing. In one memorable event former Senator Carl Levin attended a HARP meeting and awarded the group a $20,000 federal grant.

HARP also had a capable president, Ingemar Johansson. Johansson, an executive for 30 years with the county’s Community Mental Health agency, had already distinguished himself as a civic leader during a decade of organizing and advocacy that led in 2005 to the opening of Benzie Bus, the county’s public transit agency. He and his wife, Lisa, are peerless musicians and in 1982 formed Song of the Lakes, a popular folk music band whose bright sea shanty catalog serves as the soundtrack of Benzie County.

In other words Johansson was a noted citizen advocate when he sought $350,000 to buy the Kuck property. He found a willing audience at the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy in Traverse City, which has been active in land conservation in Benzie since its founding in the early 1990s. The conservancy purchased the property in 2018 under an agreement that it would be reimbursed. The payback came fairly quickly from grants awarded by the state Department of Natural Resources and several foundations.

celebrates the formal opening of Platte River Park on Saturday May 17, 2024. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

HARP has raised almost $900,000 more to establish a paved trail, several river bank viewing platforms, and a kayak and canoe launch. The new infrastructure was displayed on Saturday in the park opening. HARP donated the park to Homestead Township and is intent on raising an endowment to ensure the township has a permanent source of funds for its maintenance. Johansson also says $2 million more is needed to complete other assets including a new entrance, a pavilion and picnic area, a trail system, a riverside boardwalk, and a walkway to the Honor village center.

“We’re not finished,” said Johansson. “The whole gist of doing all this stuff is not just because it’s nice, and it’s fun and it’s beautiful. It’s about economic development, right? It’s about attracting new people to stop in the village — you know, the whole thing that happens when people stop in a place. Place making is what the whole park is.”

There’s two more inspiring details about Platte River Park. Its development occurred during a particularly raucous period in Michigan and the United States. The COVID pandemic slowed but did not stop the fundraising, design, and construction of the park’s initial infrastructure. Nor was the idea of a new public park, a big one at that, snared in the ugly web of contemporary politics that hangs over Benzie, the state, and the nation. From the outset Platte River Park made sense to Honor residents because it featured goals that matter. A persistent group of visionary residents succeeded, with public acclaim, in conserving a beautiful place as a durable asset to their community. Bravo for a job very well done.

— Keith Schneider