to play the Blues in Chicago. In March he toured Australia.

Before the country scrambled itself into an almost unrecognizable mess. Well before actually, there was a place on Chicago’s South Side called Theresa’s Lounge where every weekend the city’s best Blues were played in a deep song voice and a melancholy tone. Junior Wells and Buddy Guy were regulars. So was James Cotton. I was once at Theresa’s in 1982 with a friend when Cotton walked in off the street, took his spot on stage, and played with such joy all the ever-shaming swirls of sadness you ever heard.

That was Theresa’s. The club embodied two central elements of the Chicago Blues. Its setting in a South Side basement showcased the best of the music of misfortune and betrayal that developed during and after the Civil War and was hauled by magnificent African American musicians, on train and river boat, to what was then the country’s second largest city. And when Theresa’s closed in 1985, after stirring audiences for 40 years, it was a clear signal that Chicago Blues was transitioning from its Black Deep South roots to something else.

It’s been a long time but Theresa’s settled back in my mind a few years ago when I met Keith Scott, a Chicago bluesman who played the basement club when he first arrived in Chicago in 1981, and is now emerging as a leading figure in the evolution of Chicago Blues. Keith’s guitar, more electric, is also more funky than the moaning guitars of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Junior Wells. In Keith’s hands, though, it’s still a magic wand of Blues – all bent notes and wailing sound.

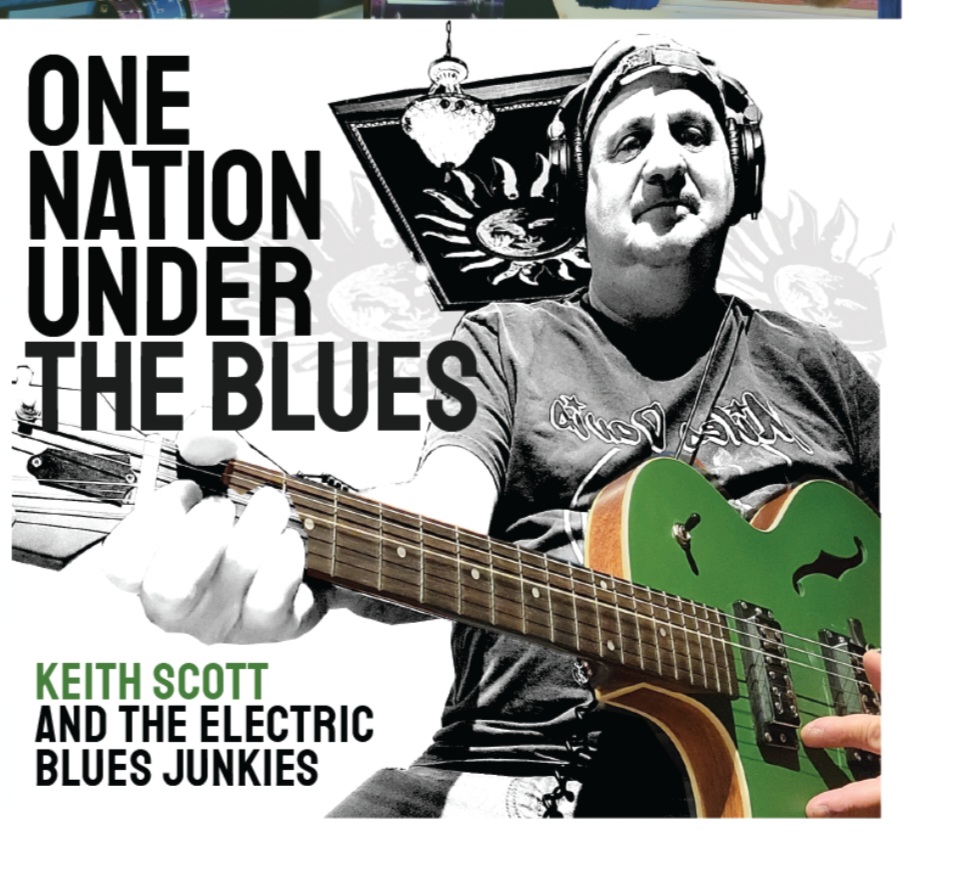

His playlist encompasses an astonishing number of tunes, from Muddy Waters to B.B. King, Ella to Aretha, and his own songs. Keith developed his strong voice under the tutelage of Hip Linkchain, another famous Chicago bluesman, who took Keith on tour to Kansas City as a backup guitarist. At one gig, Hip called Keith to the front of the band and told him to sing. He’s played all the clubs and is a regular at the House of Blues in Chicago. He’s recorded nine CDs. Hs latest is the just released One Nation Under The Blues.

In other words Keith has assembled all the musical pieces for his well-earned prominence. But it’s Keith’s back story that makes his career, and its demonstrated value to Chicago Blues, so distinctive. Other than the years of hard work perfecting his craft Keith doesn’t share in any way the hardship, upheaval, and racism that shaped the African American musicians who developed the city’s Blues scene.

He was born 60 years ago in White Plains, a suburb of New York City, and spent his early childhood in New Rochelle, a few miles away. When he was 12 years old the family moved to West Palm Beach, Florida where Keith attended an exclusive private school and got serious about teaching himself how to play electric guitar, a Univox he picked up one day. He was first attracted to Led Zeppellin and Pink Floyd, the sounds of the record albums he played at an uncle’s house. By the time he started college at the University of Florida he’d developed sufficient proficiency to attract the attention of a classmate whose boyfriend had a rock band. Keith joined it and fell in love with music and the lifestyle of a working musician. His academic life began to close as his life in music blossomed.

His pivot to the Blues occurred after he was introduced to Steve Arvey, a young and well-regarded Florida band leader and Bluesman. He met Muddy Waters and Matt Guitar Murphy, who’d just starred in the Blues Brothers movie. He also missed classes and his grades diminished as Keith fell for the Blues sound and its history. “The origins of the music, the roots, and their approach to music,” Keith said in an interview for this article. “It changed around what I wanted to do. I just pursued it.”

When Arvey invited Keith to play in Chicago, and settle there, Keith agreed. He dropped out his junior year, went to Chicago to live in a small apartment with Arvey and Arvey’s girlfriend. They played Blues clubs all over the city. Keith’s skills led to invitations to sit in with Jimmy Dawkins and Sammy Fender and Hip Linkchain, and in bands led by their friends. His career as a Chicago bluesman, a white bluesman from the suburbs, was launched.

“I went around to different clubs. The Checkerboard, Theresa’s. I just went out every night and tried to sit in and jammed,” Keith said. “I met so many legends those first few weeks, I thought this was just meant to be. People took my number and they started calling. The next thing you know I was playing all over the place. It was amazing.”

like Iron Fish, a craft distillery in Manistee County, Michigan. (Photo/Keith Schneider)

“He’s different,” said Arvey in an interview. “Keith can play. He’s never going to be known to people like Jimmy Dawkins or Sammy Fender. But he’s definitely part of the Chicago Blues. He’s earned that.”

“You get guys that come to Chicago with their guitars and they say I’m gonna learn the blues and play the blues,” added Carl Snyder, a peerless Chicago Blues pianist. “They bring a lot of ego with them before they learn anything. Keith was never like that. He was very modest, easygoing. He was relaxed about the whole business. I remember him telling me that his mother was a musician. He started playing gigs with her in Florida at a very young age and that experience soaked in. He just had kind of an easygoing approach to things.”

A friend introduced Keith about a decade ago, not long after Stormcloud, our fine local brewery, opened in Frankfort, Michigan. It was winter and after Keith’s set we had a chance to talk. Along with bearing the same first name, I immediately learned Keith and I were tied in other ways. He confirmed what I already knew – Keith is Jewish. Bar mtizvahed in West Palm Beach. He is, in Yiddish, a “landsman” (pronounced lunds-man), a Jewish man. At that moment Keith and I were likely the only two Jews in Benzie County.

I quickly learned that we had other common flourishes. He and I were born six years apart in White Plains. His mother spent part of her career as a social worker. Same for my mother.

I learned that along with the $250 or $350 (plus tips) that he earned from booking regular gigs at Stormcloud and other pubs in this region, what drew him to northern Michigan was his devotion to fishing. He asked if I fished? I told him, no, I was a writer. I spend enough time alone in my head. In fact, I said, he was only the second Jew I ever knew who liked to fish. Howlin’ Wolf fished, he replied. Bluesmen, he said, took their rods with them when they toured.

Keith surprised me with what he said next. Fly fishing was like music. He liked the sound of the cast, the flowing stream, the splash a fish makes when it hits the fly. He liked the work it took to master casting a fly precisely where he needed it to go, just like he’d worked hard to command the sound a skilled blues musician makes with his guitar.

I asked Keith about it again during an interview for this article. “When I was growing up I remember seeing books around the house and pictures of people fishing in Montana, on those famous rivers like the Yellowstone,” he said. “I was always fascinated with cold water and trout. I’ve fished that river. I think I’ve fished almost every great trout stream in the country. I play to pay for the fish.”

“I get the kick out of fly fishing,” Keith added. “It’s just like the music. Fly fishing has rhythm to it. You have to have rhythm to do it right. It’s funny, you know? There’s people that can’t get the music. Some people can’t get the fly fishing. I never say anything to anybody, but I know.”

Before the pandemic when Keith’s schedule coincided with mine he stayed at our house in Benzonia. During those visits he talked about the other dimensions of his life as a working musician.

Music is an instinct, a passion, as it must be for professional musicians. And because talented musicians are everywhere and competition is ferociously keen pursuing a professional career requires discipline and entrepreneurship. He learned those skills from his father, a salesman for Krebs Stengel, a family-owned furniture company based on Lexington Avenue in New York City.

heard him play at a festival last year in Ireland. (Photo/Keith Scott)

As his career as a backup guitarist began to change at the start of this century Keith started to book solo gigs for himself. They fit his life as a single man who likes to travel and fish. They pay well enough to provide a decent annual income. And the Internet has made the enterprise much easier. He developed a Website, markets himself on all the social media, and identifies places to play on Instagram and Facebook. He sends club owners and managers a message with a link to his Website and lets them know he’s available to play. The technique works very well. Keith’s booked annual tours on the West Coast and Canada, played big festivals and toured Europe. In March he spent two weeks touring Australia at the invitation of Dean Bird, a promoter who heard him play at a festival in Ireland. He’s playing the Calgary Blues Fest in August.

Keith’s bread and butter is playing the Chicago clubs, and the brew pubs and bars in towns on the Lake Michigan shoreline in two states. He’s happy and satisfied. “I’m not like a New York salesman,” he said. “I’m successful in what I’m doing. Maybe I should be doing more? Getting better known? I don’t know. I’m excited, though about where I am with the music. I travel. I meet a lot of great people. I get to fish when I want. It’s good.”

— Keith Schneider