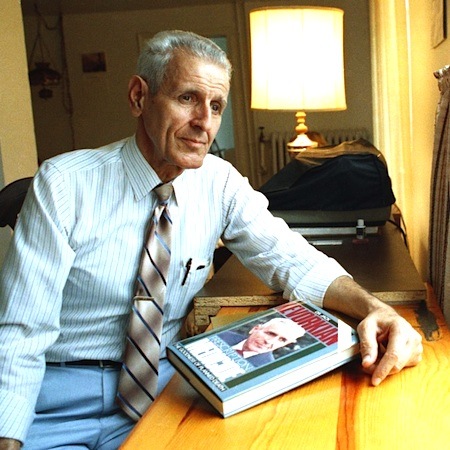

Jack Kevorkian met death on Friday without any assist. Three years ago I wrote his advance obituary for the New York Times, which published it on the front page on Saturday.

Kevorkian was an odd and immodest man of scant talent who became a signpost of his time principally by being an untiring zealot. He lived alone. He had no other responsibilities other than himself. That made it possible for Kevorkian to focus such uncompromising energy on a specific objective — making the case for better choices at life’s end. He did some good. But his life seemed so cheerless, so parched, so pathological.

Here’s the start of my unedited piece sent to the Times in 2008:

Jack Kevorkian, the crusading medical pathologist from Michigan who challenged social taboos about disease and dying, willfully defied prosecutors and the courts, courted national celebrity, and spent eight years in prison after being convicted of second degree murder in the death of the last of the 130 terminally ill patients whose suicide he assisted, died today in Royal Oak, Michigan where he’d lived for years. He was 83 years old.

From June 1990, when he assisted the first suicide, until March 1999, when he was sentenced to serve 10 to 25 years in a maximum security prison, Dr. Kevorkian was the central figure in a tumultuous national drama about the medical ethics, legal rights, and religious morals of enabling sick and suffering people to end their own lives.

His critics and supporters generally agree that as a result of Dr. Kevorkian’s stubborn and often intemperate advocacy for the right of terminally ill patients to choose how they die, hospice care has boomed in the United States. Physicians have become more sympathetic to pain, and more willing to prescribe medication to relieve it. In 1997, Oregon became the first state to enact a statute making it legal for physicians to prescribe lethal medications for terminally-ill patients to end their lives. In 2006 the United States Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that found Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act protected a legitimate medical practice.

During those nine years, Dr. Kevorkian’s confrontational strategy turned his cause into a running media story, consuming thousands of column inches in national newspapers, gracing the covers of national magazines, and serving as the focus of popular television news programs, including CBS News’ “60 Minutes.” Moreover, his nickname, Dr. Death, and his self-made suicide machine, which he variously called the “mercitron,” or the “thanatron,” became fodder for late-night television comics.

Given his obdurate public persona and his delight in flaying medical critics as “hypocritic oafs,” Dr. Kevorkian invited and reveled in the public’s focused attention, regardless of its sting.

The American Medical Association in 1995 called him “a reckless instrument of death” who “poses a great threat to the public.”

Diane Coleman, the founder of Not Dead Yet, a right-to-life advocacy group that once picketed Dr. Kevorkian’s home in Royal Oak, a Detroit suburb, criticized his approach. “It’s the ultimate form of discrimination to offer people with disabilities help to die,” she said, “without having offered real options to live.”

But Jack Lessenberry, a prominent Michigan journalist who closely covered Dr. Kevorkian’s one-man campaign, said, “Jack Kevorkian, faults and all, was a major force for good in this society. He forced us to pay attention to one of the biggest elephants in society’s living room: the fact that today vast numbers of people are alive who would rather be dead; who have lives not worth living.”

See the published obituary here.

— Keith Schneider