CAJAMARCA, Peru – North of Lima, 350 miles, this regional capital is spread across a high mountain valley near the northern terminus of the Andes Mountains. Spanish conquistadors began their conquest of Latin America here in the early 16th century when they murdered the last Incan emperor. The room where the Incan chief is said to have spent his last days is a half-block from Cajamarca’s central square. Roman Catholic cathedrals flank the southern and northern boundaries of the square, which is alive with strollers and skateboarders and people warming themselves in a bright winter sun.

The scene of order that greets visitors, the clean streets and the shops that stay open well past sunset, is a display of order that while not new isn’t all that old either. In the 1980s this city, which today numbers 250,000 residents, was one-third as large and engulfed by the same national economic depression that produced rampant joblessness, and inflation that essentially rendered the currency worthless. In the 1990s, Cajamarca and the villages in the surrounding Andes became a place where leaders and soldiers of the Shining Path, the leftist insurgency, came to heal during the nearly decade-long civil war that killed 70,000 people, according to government estimates.

Members of the Shining Path were a murderous bunch. With death threats, coercion, and targeted killing they sowed fear and disorder. Those who could leave the country, did. Peru’s president, Alberto Fujimori, responded by forming death squads that attacked the insurgents and also murdered a good number of innocent citizens. Fujimori was prosecuted for crimes against humanity, convicted, and in 2009 sentenced to a 25-year prison term.

Earlier this month a social scientist from Australia, Martin Scurrah, who’s spent much of his adult life in Peru, explored the history of Peru’s dark era with me. As his narrative neared its end I remarked that in its basic details — severe economic pain, political insurgency, social disorder, rampant death — it resembled what the United States is now experiencing. Peru’s recent story also produced a contemporary chapter that could hold lessons for the United States.

Peru is no longer a nation of paranoia and doubt. Its economy, driven by a strong minerals and agriculture sector, is growing. Incomes are rising. The middle class is expanding. No doubt there are endless problems here, as in any country. But the central national government is gaining credibility and introducing important reforms, including approving legislation to secure natural resources and strengthen the management of water. Since 2009, Peru has formed two new environmental regulatory agencies to pursue both objectives.

The narrative of the U.S. isn’t nearly as sanguine. A political insurgency, financed in large part by the producers of fossil fuels, has overtaken Congress and too many state governments. Their aim is to foster agitation and fear, and as we learned last year, government shutdown and default.

The consequences for the country have been profound. Just six years ago the economy collapsed. Economic depression still exists for tens of millions of American adults, many of whom — if they vote at all – support the delusional lawmakers who are lowering their wages, eliminating opportunities for their children, and weakening rules so that workplaces are more dangerous, water is more contaminated, air is dirtier, and cities are more prone to being drowned by hurricanes or blown apart by tornadoes.

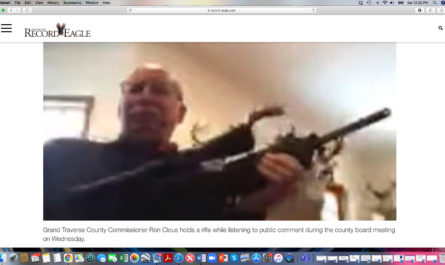

Yet even with this steady erosion in the American way of life, the most visible and dangerous element of America’s political insurgency right now is its fidelity to guns. That national deviancy has produced an unusual era of civic bloodshed that is tightly wrapped in what too many Americans think is the armor of cultural values and seemingly bulletproof Constitutional protections. That can be the only explanation for why Americans tolerate the massacres — in public schools and universities, on the streets, in malls and theaters and even high school reunions — that have become weekly events.

Severe economic pain. Political insurgency. Social disorder. Rampant death. Peru found a path out of its darkest decades in the 1980s and 1990s. In Peru’s story is hope that the United States will do the same.

— Keith Schneider

2 thoughts on “Peru’s Recession and Insurgency Revives Its Democracy; Example For the U.S.?”