PANAMA CITY, Panama – It was an elaborate, even theatrical display of national pride and elite engineering. On January 19, Panama’s four-quarter, red and blue star flag gleamed in bright morning sunlight as a 2,300-ton steel gate slid into place inside a colossal new lock of the Panama Canal.

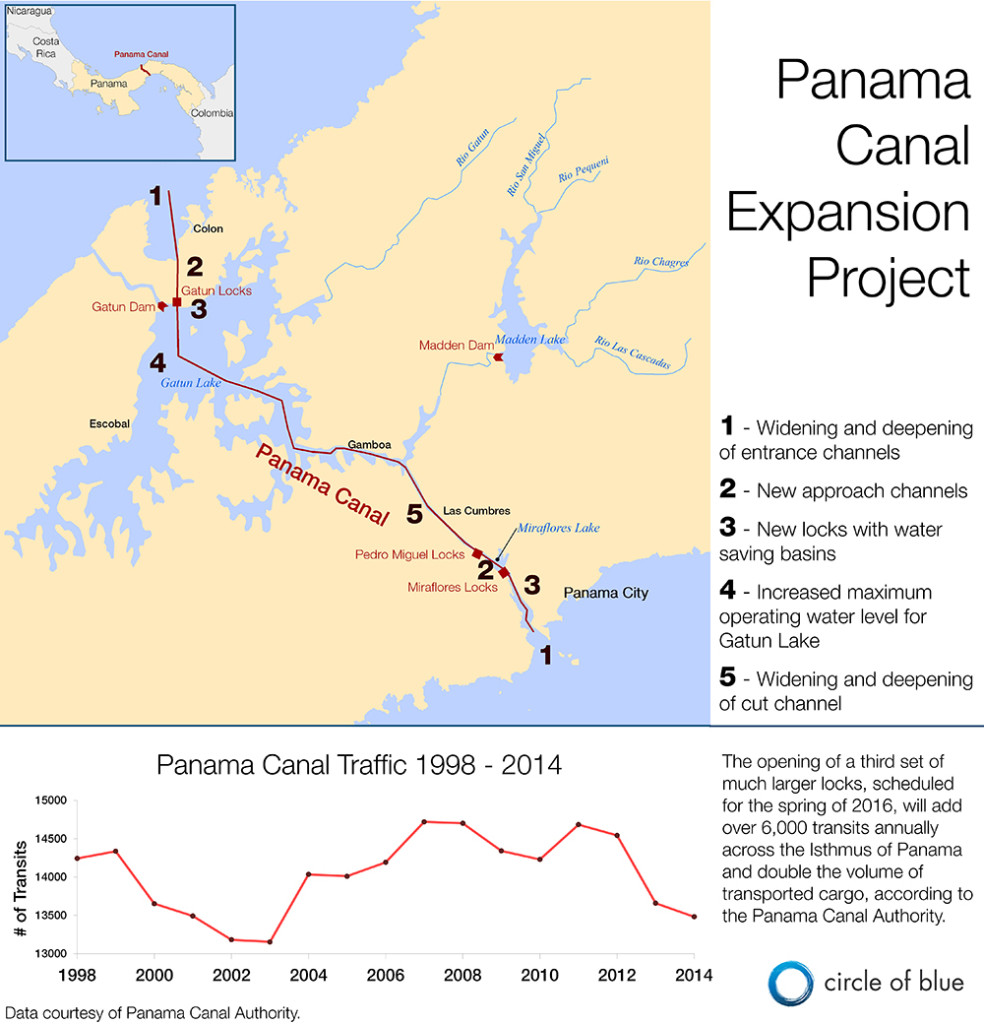

It was the first of eight mammoth gates, ranging in height from seven to nine stories, to be installed in the three concrete locking chambers near the canal’s Pacific entrance. Almost 90 percent complete and scheduled to open for commercial traffic in the spring of 2016, the roughly $US 6 billion canal expansion is expected to double the amount of cargo that crosses the Isthmus of Panama, to 660 million metric tons per year.

Thousands of men and hundreds of trucks and excavators, like a colony of motorized ants, swarm through the construction site to bend steel and pour concrete. The scale of the project to excavate new channels, widen existing shipping corridors, and complete three new lock chambers on the Pacific side and three more close to the Caribbean make the canal expansion a 21st-century parallel to building the Egyptian pyramids.

With its much larger locks lifting and lowering much bigger ships for the day-long crossing, the expanded canal is projected to alter global patterns of energy and food production and trade. Analysts also anticipate that the additional transport capacity will shift water use and supply, particularly in the United States and China, the primary producers and consumers of goods shipped through the canal.

The expansion project’s effects on Panama’s economy and management also are extraordinary. Both the Caribbean and Pacific entrances are swollen with new construction. Proposals for big power generating, fuel storage, logistics, and transport projects in the canal corridor are under review by national authorities.

The canal’s ability to drive economic growth is evident in Panama City, the capital, where an impressive skyline of seaside white towers bloomed in the last decade. The Pacific coast city of 1.5 million people has quickly become a modern maritime hub where jobs are plentiful and employees are needed for almost 100 banks holding over $US 100 billion in assets, hundreds of shippingfirms, and busy container terminals.

The canal expansion also is attracting developers of mega-projects along the Caribbean coast who are testing Panama’s regulatory agencies with proposals that could have substantial effects on the nation’s water resources and tropical landscape. The projects include a $US 6.4 billion open-pit copper mine powered by a 300-megawatt coal-fired power plant, a $US and a $US 4 billion residential resort.

“The expansion project is pushing the country in new directions,†said Onesimo V. Sánchez, the manager of the Panama Canal Authority’s economic research unit. “It’s been a long road to discovery of yourself. It’s changing Panama.â€

Contractors here and in the United States say that the expansion project also can be seen as a global model of astute construction management. The opening of the expanded canal is expected to cost under $US 6 billion, just 10 percent more than the original $US 5.25 billion price tag.

Its commercial opening, now projected to occur in the spring of 2016, comes a year later than anticipated. In contrast, the construction of the $US 3 billion Olmsted Locks and Dam on the Ohio River, the largest inland navigation project in the United States, is more than $US 2 billion over budget and decades late in opening.

“We had a lot of experience in construction, moving equipment, applying our experience in managing the canal before the expansion,†said Ilya R. Espino De Marotta, the Panama Canal Authority executive vice president who oversees the project. “It’s helped give us the know-how to do this project well. It’s not easy. Redoing a bathroom is not easy. For a project this size, we’re doing well.â€

Effect on Trade

In every major study that assesses the new canal’s influence on trade, including a 2013 report by the U.S. Maritime Administration, researchers find that among the project’s big effects will be increasing the flow of American energy products to China and Japan.

The reason relates to the canal’s size. The new locking chambers, of which there are six, are longer, deeper, and wider than their forebears, which translates into a three-fold increase in a chamber’s holding capacity. The supersized locks enable contemporary Capesize bulk ore vessels, big liquid natural gas carriers, and much larger liquid petroleum and bulk chemical tankers to make the run from American ports to Asian ports.

Natural gas, propane, and petroleum liquids shipments from the United States to Asia are expected to grow substantially. Coal exports from the United States to China also could expand.

The Maritime Administration study noted that because the expanded canal and larger ships will make it less expensive to export American harvests of soybeans, corn, and wheat to Asian markets, American grain production should increase.

How much less expensive is unclear. Shippers await the Canal Authority’s new toll structure for the expanded locks. In August 2012, Alberto Alemán Zubieta, the canal’s former administrator, illustrated the projected cost savings.

A shipment of eastern U.S. coal from the Port of Baltimore to Xiangang, China in a Panamax vessel that fits the existing canal costs about $US 35 per ton, said Zubieta. Shipping the same amount of coal between the same two cities in the larger post-Panamax vessels would cost approximately $US 25 per ton.

Zubieta also estimated that grain transported to Asia from the American Midwest and Great Plains would cost about $US 50 per ton in the larger bulk carriers, or $US 5 less per ton than in the Panamax vessel.

“Grain exported from the U.S. Midwest, and new opportunities for exports, such as coal, oil and petroleum products, and liquefied natural gas (LNG), may be able to capitalize on expanded Panama Canal capacity,†said the authors of the U.S. Maritime Administration study. They added: “Impacts are likely to be significantly different by geographic region and by the type of product transported.â€

Effect on Water Reserves

The effects of these trends on global water supplies could be substantial. International trade in farm and industrial products accounts for 2,320 cubic gigameters of water use annually, according to a study in 2011 by UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, a water research institute in Delft, the Netherlands. (A gigameter is 1 billion cubic meters, or 264.1 billion gallons.)

Trade in crops contributes 76 percent to the total volume. Trade in animal and industrial products contributes 12 percent each, according to the UNESCO-IHE study.

The Panama Canal currently accounts for 3 percent of global trade volume, a share that is expected to increase to 6 percent to 7 percent over the next decade. In terms of water use, 7 percent of global trade equals roughly 174 cubic gigameters of water annually, or 46 trillion gallons. That’s equivalent to a third of all the water used in the United States annually, according to the most recent assessment of American water use by the U.S. Geological Survey.

The authors of the UNESCO-IHE study found that global use of water in trade was not evenly distributed, especially because the trade in energy and agricultural products – the largest users of water – involves producing countries using their waters, and consuming countries saving water. “Several countries heavily rely on water resources elsewhere,†said the report’s authors, “and many countries have significant impacts on water consumption and pollution elsewhere.â€

Two cases in point involve energy and agricultural products transported through the expanded Panama Canal. In the United States, coal production to serve the increased exports to China would exacerbate water pollution from acid mine and toxic metal pollution in the eastern coal belts of Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana. It also would put more pressure on already scarce freshwater reserves in Asia to cool coal-fired power plants in China.

The heightened trade in petroleum products and natural gas from the United States is likely to affect water supplies needed for fracking in the oil and gas fields of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and the Great Plains. Under current weak and largely voluntary water treatment measures, an increase in hydraulic fracturing could increase water pollution from fracked wells.

In China, though, increased use of American natural gas to fuel power plants would reduce water consumption. Generating a kilowatt of electricity from natural gas uses 60 percent less water than generating an equal amount of power from coal, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Similarly, increased grain trade between the United States and Asia has consequences for water use in both places. The Midwest grain belts, which stretch from Ohio to Missouri and Iowa, are water rich. But the eight-state Great Plains, which supports a $US 30 billion agriculture and livestock industry, could experience canal-related water supply pressures.

The Great Plains, which relies on the Ogallala Aquifer to produce one-fifth of the 410 million-metric-ton annual U.S. corn and wheat harvest, faces a new era of reckoning. The Ogallala’s users pump significantly more water out of the aquifer than filters back into the ground. Increased grain production to serve Asian markets will put more pressure on the Ogallala.

Shipments in Energy and Grain

As it is, shipments of American grain and energy resources through the canal are increasing. In 2014, 48.6 million metric tons of grain, most of it produced in the United States, moved through the canal from the Caribbean to the Pacific side for shipment to Asia, an increase of more than 50 percent compared to 2013.

Shipments of petroleum liquids from the Caribbean side to the Pacific, most of them refined and processed along the U.S. Gulf Coast, reached 32.3 million metric tons in 2014. Coal and coke shipments, principally from Colombia and eastern U.S. coal fields, totaled almost 14.3 million metric tons.

In all, bulk container shipments to Asia totaled 89 million metric tons or 27 percent of the tonnage handled by the canal. When the much smaller reverse Pacific to Caribbean trade is included, bulk chemical and energy shipments accounted for $US 687 million in tolls, or 36 percent of the $US 1.9 billion that was paid to the Panama Canal Authority by merchant ships last year, according to authority figures.

Panama Effects

From her office in the American-built Panama Canal Authority headquarters, decorated with a coat rack that holds her pink construction helmet and pink safety vest, Ilya R. Espino De Marotta patiently supervises the mammoth project that is shaping her country.

Appointed two years ago to succeed Jorge L. Quijano, who became the authority’s administrator and chief executive, Marotta is one of the highest ranking women in the country, and is so well-respected she’s a candidate for the Canal Authority’s top job as administrator, or the nation’s top job as president. The next presidential election is scheduled for 2019.

Marotta’s reputation rests on her characteristic unflappable and engaging demeanor. Those personality traits served her and the Canal Authority well during several strikes by construction workers, and very difficult disagreements over contract provisions and payments to the international consortium of companies building the new canal.

“People keep asking me that,†she says in an interview with Circle of Blue. “Do I want to be president? Do I want to do something that difficult? That different from what I do. It’s not something I think about. We have to finish this project, which is hard enough. We’re close. It takes all of my attention right now.â€

Inside The Project

It should hold Marotta’s attention. Constructing the third set of locks is one of the largest and most complex construction projects on Earth right now. Like almost every other facet of the Panama Canal, the expansion is a study in history, fluid dynamics, and keen water management.

The United States took over the original canal construction project from the French in 1904 and completed it in 1914. The result is a 77-kilometer (48-mile) water route across the isthmus with groupings of side-by-side locks; one group on the Caribbean side and two more groups on the Pacific side.

In the late 1930s, the U.S. military began construction of a third set of locks but halted the effort in 1939 at the start of World War Two.

President Jimmy Carter launched the process to turn over the canal to Panamanian ownership and management in the late 1970s. Panama gradually assumed ever more management authority and expertise, and gained full control on December 31, 1999.

The contemporary expansion builds on the previous work but with 21st century principles of water use and water management, which are defined by the need to conserve water and safeguard the canal’s expansive 345,000-hectare (1,332-square mile) watershed.

Almost half of the canal’s route crosses Lago Gatun, a freshwater reservoir fed by the Chagres River and held in place by Gatun Dam. Lago Gatun, and a second big reservoir nearby, Lago Alajuela, supply the 7.6-million cubic meters (2 billion gallons) of water needed daily for 35 to 38 ships to complete the transit on the existing locks, or what is known here as “lockages.â€

Water is used to fill the old locks with water to raise ships 26 meters (85 feet) and then lower ships by the same amount. It takes 208,000 cubic meters (55 million gallons) of water per transit or lockage, according to the Canal Authority.

Before 2006, when 80 percent of Panamanian voters cast ballots in favor of the canal expansion, the authority’s engineers considered building a third reservoir to supply water for the third set of locks. Reason: filling the new locking basins would take 483,600 cubic meters (128 million gallons) cubic meters of water per lockage.

That would have meant high expense, enormous changes in land use, and evicting some of the 150,000 people who live in the watershed.

A better way involved an idea proven in Germany. Canal officials installed storage basins alongside the new locks to recycle 60 percent of the water used in lockages before it is discharged. The recycling technology enables the new locks to use 7 percent less water than the existing locks, or 193,500 cubic meters (51 million gallons) per lockage. The water savings nullified the need for a new reservoir, said Carlos A. Vargas, the Canal Authority’s executive vice president for water and energy.

“It’s smarter. It’s cheaper. It uses less water,†Vargas said.

Still, the new locks will also use more than 7 million cubic meters of water for the 13 to 15 big ships that will cross the isthmus each day. With a roughly 15 million cubic meter daily demand for water, the authority still needed a larger water supply. That problem was solved in large part by raising Gatun Dam and raising Lago Gatun’s maximum operating level by 45 centimeters (18 inches).

The authority also is dredging deeper navigation channels and controlling sedimentation by replanting tracts of forest, controlling tree cutting, and improving farm cultivation practices.

“The whole idea is not to waste water,†said Vargas. “Even in this country, with so much rain, water is a concern. When you save water, use less, it amounts to not having to build more dams.â€

The New Locks

Standing on the bottom of the canal’s nearly completed locks is an exercise in feeling small. Three lock chambers unfold in a concrete canyon nearly two kilometers long. Graders and haul trucks at one end are so distant they appear as small as pencil points. Hanging from the sides of the chamber, here and there, are men on platforms drilling bolts in the concrete. The sound of groaning diesels and whining drills fills the space.

Well over 100 million cubic meters of earth was excavated for the project. Tens of millions of cubic meters of concrete were poured, enough to construct a sizable city.

“From the start of construction in 2007 to when the first ship goes through here, it will be nine years,†said Luis Ferreira, an architect and engineer who has worked for the Canal Authority for 40 years. “It’s big. But it may not be big enough. There are ships out there already that are too big for the new locks.â€

“Imagine,†Ferreira says, spreading his arms wide. “Bigger than this. There are some people around here that think we need a fourth set of even bigger locks.â€

— Keith Schneider

One thought on “Panama Canal Expansion Will Have Big Effect on Energy, Water, and Grain in U.S. and China”