FRANKFORT, MI – The public event of the year in Benzie County, Michigan occurs here on July 4. The day begins with a parade on Main Street, continues with an art fair, a carnival, and this year a sand castle design contest on the Lake Michigan beachfront. Thousands of people roll into town while the sun is high. And as it sets thousands more come for the meteoric spectacle – the fireworks show that lights the town’s harbor and fills the sky with an escalating tempest of white sizzle, and red and blue flare.

Along with the day’s expert choreography another facet of Frankfort’s July 4 is its staging in a Lake Michigan shoreline town that dates to the 1850s, houses 1,280 residents, and has gradually emerged, like an oaf who’s worked himself into six-pack peak condition, as one of the truly handsome small ports on the Great Lakes. It’s an evolution, decades in the making, that was delayed in part by an indecorous period in Frankfort’s history when residents chased out Jewish vacationers in the years after World War Two. Had the town not made it clear with signs in restaurant windows, golf courses, and lodges — “Gentiles Only” — it certainly would have been enriched by the energy, ideas, loyalty, and investment that Jewish visitors bring.

Instead, befuddled by a short seasonal economy, content to plug along even as its population grew old and dropped by 31 percent from its 1950 peak of 1,858 residents, Frankfort withered. When I first arrived in Benzie County in 1990, Frankfort was a town preserved in clouded amber. Though it was friendly and quiet, the town felt like an antique parlor that needed a good dusting.

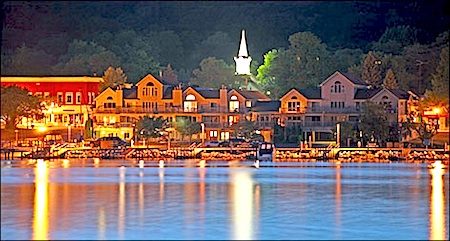

In the last five years or so, even with a national recession that worried shopkeepers and investors, Frankfort has more than perked up. The town’s leafy streets have been repaved and are accompanied by lovely early 20th century homes with gables and porches. All major avenues have broad sidewalks and lead west to the city’s beach and harbor, and the wide breakwater that ends at the black and white steel base of the Frankfort Lighthouse.

The new economic activity on and near Main Street is impressive. The Stormcloud Brewing Company just opened at 303 Main Street. Another group of civic-minded entrepreneurs bought and renovated the 90-year-old Garden Theater, the town’s sole movie house. The city and state renovated 56 affordable apartments in Patterson Crossing, near the beach, and built 37 more new workforce housing units at Gateway Village. The aptly named Gold Coast Marina, with new luxury apartments, was built along Frankfort’s marina. Last year a three-story mixed-use retail and residential building, designed by Traverse City architect Michael Fitzhugh, opened next door to the theater and the new brewery. A short walk away is the Oliver Art Center, which opened two years ago in a renovated Coast Guard Station at the harbor entrance. Several good restaurants are doing well and open all year.

On July 4, Frankfort marks Independence Day with all the pomp and delight that a small town can muster. Almost completely forgotten are the years of discrimination, the direct strike at liberty that once greeted Jewish visitors here and that played a role, maybe a bigger role than anybody ever anticipated, in impeding the town’s modern development.

Frankfort, of course, was not alone in expressing its allegiance to discrimination and anti-semitism in the years after the war. Ethno- and racial-centric resorts, and resort communities developed all along the west Michigan shoreline, from South Haven (a popular Jewish summering destination) to the hey day of Idlewild, in Lake County, where prominent African Americans summered from 1920 to the 1970s.

Frankfort’s turn against its Jewish visitors came pretty suddenly, according to people I’ve talked to who were here. Many of Frankfort’s homeowners lived in their above-garage apartments, and in similar accommodations during the summer while they rented their houses to Jewish families from Chicago, St. Louis, and Detroit. The urban Jewish culture, its particular dietary restrictions, its energy and volume and class distinctions are said to have irked Frankfort residents at a time when the town was at a postwar peak in population and economic activity.

Anti-semitism was already a widely accepted principle in the region, a civic value. Crystal Downs, an upper crust golf resort and residential area north of Frankfort, memorialized its antipathy with a message at its entrance that was carved, literally, in stone: “Gentiles Only.”

That same message began to appear in the town’s restaurants, and at some of the inns and lodging businesses, and at retail stores, said people I talked to. Jews got the message straight away and stopped summering in Frankfort in the early 1950s. They left the rest of Benzie County alone, too, and never returned except for a family here and there that rents a cottage for a week or so. I’m the only full-time resident of Benzie County that I know who’s Jewish.

I feel secure and welcomed in this county, which I am also convinced is the most beautiful place in Michigan, and one of the most beautiful in the world. It’s not easy to live here, though discrimination and bad behavior are not the reasons why. Rather, it is tough to make a living here, a goal that requires constant evaluation and persistent execution. But once you’ve figured it out, and if a rural lifestyle is intriguing, then there is no better place to be.

Frankfort’s development as a destination for art, film, dining, and craft beer adds to its evolving history as a summering resort. It’s the kind of quaint, authentic, reasonably priced, safe, and engaging beachfront town that Jewish families really like. I imagine that pretty soon more Jewish vacationers will alight here. When they do Frankfort will open its arms and say, “Glad you’re back.”

— Keith Schneider