Montgomery, which has occupied one bank of the Alabama River since 1819, never deliberately set out to distinguish itself as the white hot furnace of American racial injustice, or the historic hearth of reconciliation. That’s what Alabama’s capital has become, though.

Yesterday the city of 200,000, where slaves were sold and where the Civil Rights movement was born, took another memorable step. It elected Steven Reed, Montgomery County’s first African American probate judge, as its first black mayor.

In the age of a maniac in the White House whose words enflame white supremacist hatred, Montgomery is a welcome lesson in cultural evolution. The city’s reckoning with its cruel past, and the opportunities afforded by its civil advance also has produced two more well-earned outcomes.

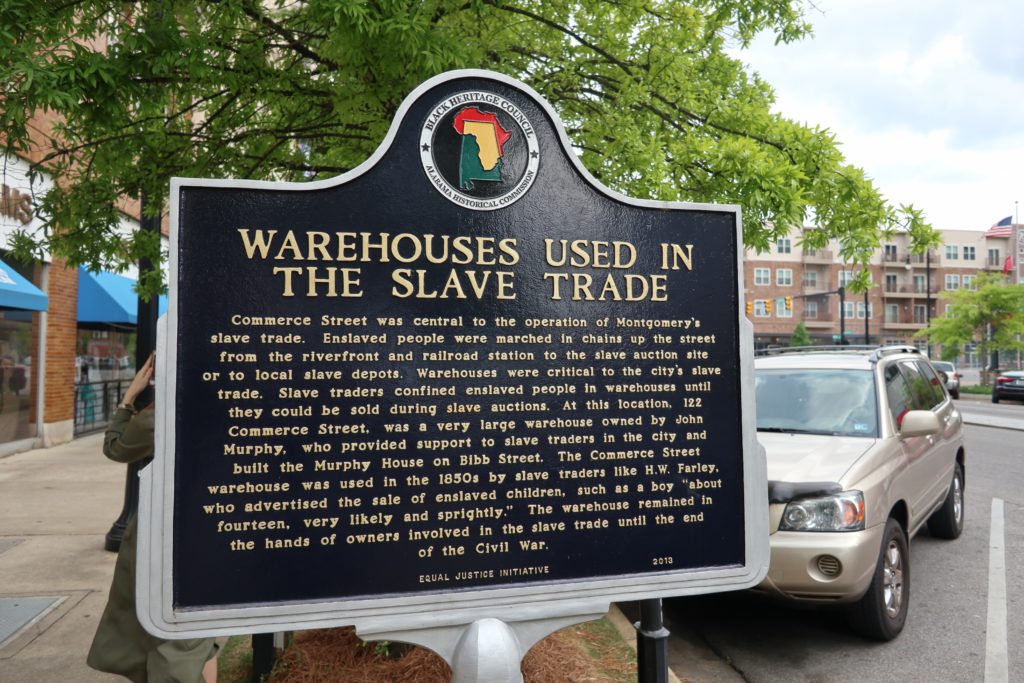

The first is the flourishing tourism trade centered on dramatic new expressions of racial injustice that are articulated in an emotionally gripping national monument to victims of lynching, and a sister museum of slavery and mass incarceration. Both opened in April 2018. The two attractions express a more urgent and contemporary narrative of bigotry that ties slavery, the Civil War, lynching, segregation, and civil rights to the current era of street shootings and mass incarcerations of African American men.

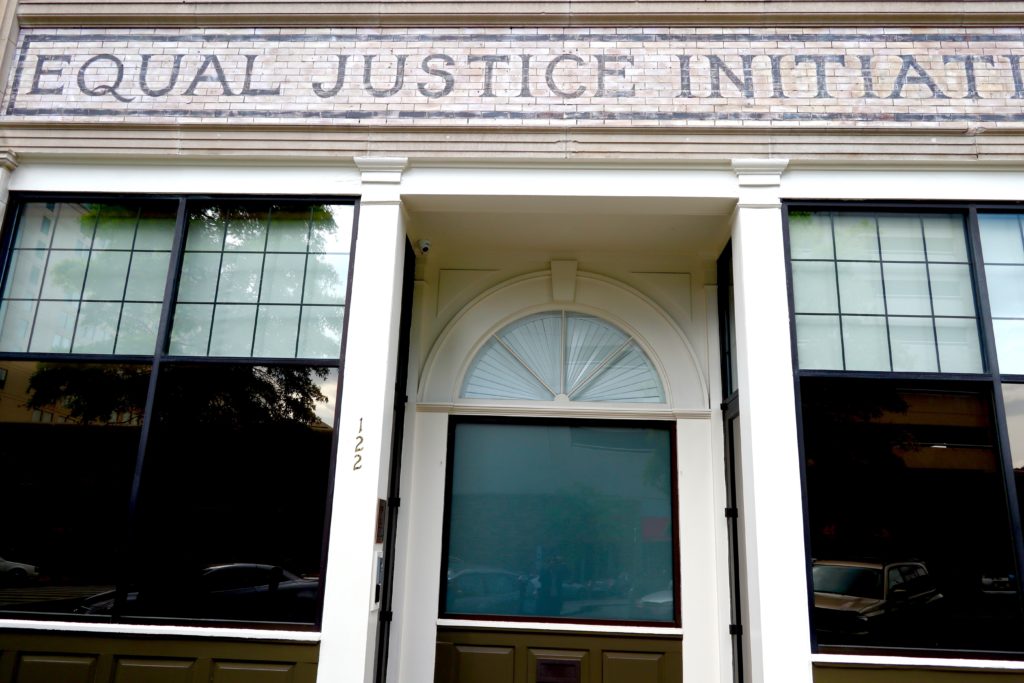

The second is the emergence of Bryan Stevenson as a national human rights hero. Stevenson is a decorated civil rights lawyer who founded the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery to defend and liberate wrongfully convicted black death row inmates in Alabama. Stevenson was barely known in the city and state as recently as three years ago, even though he won a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (the ‘genius’ award) in 1995.

A lot changed since. Stevenson published a best-selling memoir about his work, “Just Mercy,” in 2014. The new museum and memorial, which he inspired and helped to design, are attracting throngs of visitors and encouraging a surge of downtown construction. The Equal Justice Initiative campaign to install historic markers at sites where lynching occurred gains momentum in counties across the country.

This year HBO broadcast a documentary on Stevenson, and Hollywood produced a major motion picture, “Just Mercy,” that stars Michael B. Jordan as Stevenson and Jamie Foxx as one of the book’s central characters.

As if the United States needs another reason to liberate the White House from its current occupant, here’s one more. Electing a Democrat as president would elevate Stevenson as a legitimate and logical nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court.

I interviewed Bryan Stevenson last spring for a New York Times article on the surge in Montgomery’s downtown development galvanized by his inspiration. He was informative, gracious, and determined. I asked him how his new role as a developer fit. He said he had no choice. No one else had stepped up to do what was so plainly needed in educating America about the horror of lynching and the racially motivated scourge of mass incarceration.

He became a developer by necessity. “I became focused on cultural spaces for people to deal honestly with the past. We’ve done a terrible job in America of talking honestly about slavery and segregation,†said Stevenson, who moved from Atlanta to Montgomery in 1989. “I knew it was going to be significant because it hadn’t happened in America and it needed to be done. I just wasn’t sure how much interest there would be.â€

He built it, and they came. From the steps of the State Capitol, overlooking a historic business district where the Confederacy and Civil Rights movements were born, the ripple effects of the museum and monument projects are visible on almost every street. New hotels, and thousands of square feet of retail spaces, offices, entertainment venues, and residences are under construction.

Montgomery’s burst of development, the second wave of downtown construction since 1990, is reinventing the city. The once-empty and dilapidated late 19th and early 20th century brick commercial buildings on Dexter Avenue, end point of the 54-mile civil rights protest march from Selma in 1965, are being restored and put to new use as retail, office, and residential spaces.

Blocks away, and close to where Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus, the 112-year old, 12-story Bell Building, once the city’s tallest office structure, is being remodeled into 88 apartments at a cost of $25 million.

Around the corner, within easy walking distance of a museum to the Freedom Riders that is housed in the same Greyhound station where civil rights activists were attacked in 1961 by a white mob, a 114-room, $12.5 million, Staybridge Suites hotel is nearing completion.

Intriguing personalities and relationships, consistent with the Civil Rights movement’s history in the city and the South, are being formed in Montgomery around the development. Mark Buller and his wife, Sarah Beatty Buller, are Jewish developers who live in Manhattan and own Marjam, a construction supply business that operates in Brooklyn and 49 other cities in the United States and Canada.

Mr. Buller bought a failing lumberyard in Montgomery in 2009. During a visit downtown, he was struck by the beauty of a square and fountain at the foot of Dexter Avenue, and the handsome federal-style exterior of the empty Kress Building, once a bustling department store. Inspired by the city’s history and business opportunities, the Bullers paid $5.2 million to buy the Kress Building, 10 other empty buildings near the square, and several city-owned lots.

They plan to invest $100 million to turn the 247,000 square feet they own along Dexter Avenue and adjoining Montgomery Street, and 55.5 undeveloped acres elsewhere in Montgomery, into mixed-used residential, retail, office and entertainment projects. All will be designed by local professionals and constructed by Montgomery tradesman and contractors.

Their first impressive project on Dexter Avenue is the $25 million renovation and expansion of the 92-year-old Kress Building, which reopened last year as 110,000 square feet of retail space on the first and second floors, office space on the third floor, and 28 residential units on the newly added fourth and fifth floors.

“The city has wonderful bones for redevelopment,†Mark Buller told me. “We’ve met wonderful people. I feel strongly that we are on track to make things better, including for our family and our business.â€

Sarah Buller added this: “It’s a personal journey as much as professional,” she said. “I’m a Yankee from Boston. It’s been enriching to go and work in this place. From a personal perspective, it’s like wow!”

The Equal Justice Initiative just spent almost $1 million to buy an empty city lot and an empty 25,000-square-foot warehouse near the museum for 150 parking spaces and a $4 million visitor center for the museum ticket office, store, and a soul food restaurant.

I talked to the former mayor, Todd Strange, about the fire that’s been lit under his city. “We’re confronting our past. We’re owning the issues that Bryan is talking about,†said Mayor Strange, a Republican who’s led Montgomery for a decade. “The Memorial for Peace and Justice is amazing. It’s powerful. Why in the world do you think we thank Bryan Stevenson every chance we can. And he hasn’t asked for a dime.â€

All told, Bryan Stevenson has helped open a much broader path to public sector achievement for Montgomery’s new mayor. Steven Reed starts his job with economic advantages and a new measure of racial fairness that no Montgomery mayor before him has ever enjoyed.

— Keith Schneider